Researchers at Duke recently brought attention to the fact that although AIDS-related deaths have decreased overall, young people aged 10 to 19 years have experienced a 50 percent increase in mortality in recent years.

Dorothy Dow, assistant professor of pediatrics, has been working in Moshi, Tanzania to determine why adolescents were not taking their medicine—which contributes to the rising rate of mortality in the age group—and to design an intervention that would address these behaviors.

“By far and away stigma plays a role in why [adolescents] don’t want to come in to get tested or why they don’t want to take their medication, so we wanted to develop some way to make the youths themselves value the fact that they can take medicine and that it will help them live a happy, healthy life,” Dow said.

Sauti ya Vijana—meaning “Voice of Youth”—is a 10-session, group-based intervention program that allows adolescents to talk about their worries and stresses and provides cognitive behavioral therapy.

Dow’s work found that young people who openly discussed their status with a family member or healthcare professional tended to have fewer mental health difficulties than those who found out on their own.

During the group sessions, participants discuss stigma they face, their support systems and how they found out their status, and they often learn they can live a healthy life if they take their medicine. The sessions aim to dispel the myth that being HIV-positive is a death sentence.

“Within themselves, it's really using CBT methods to say, ‘I have HIV but I’m just as good as another person,’ so they feel happy and they can go on and do all the things their peers do,” Dow said.

The sessions also encourage disclosure to partners by explaining transmission and sexual health.

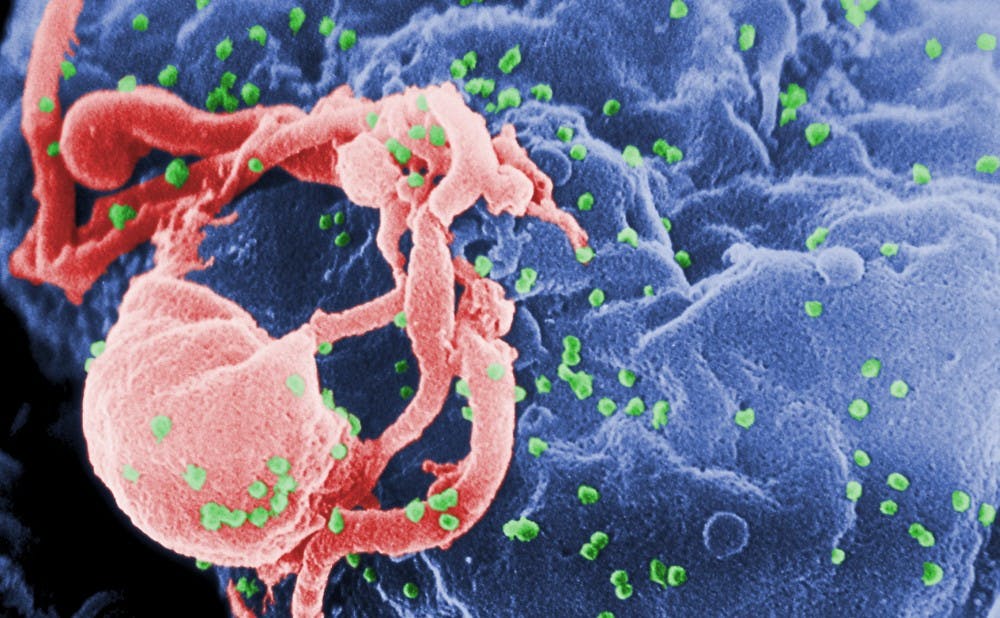

Preteens and teenagers are encouraged to take their medicine to get their viral loads to an undetectable level, meaning that the HIV is still in their body but would not transmit the virus to another person. They are also encouraged to use condoms to prevent getting a more resistant strain of HIV and to protect against STIs.

During the last of the 10 sessions, the adolescents discuss their values and what’s important in their life. They also reaffirm the intrinsic motivation to take medicine instead of just being told by a doctor that they need to.

“The hope is that all of these tools, these coping strategies and new knowledge will help them live their life in a way that they just take their medicine because they value it, and they know that they can go on and live a full life just like someone who does not have HIV,” Dow said.

Anti-retroviral therapy has allowed more children diagnosed with HIV to live into adolescence. A phenomenon therefore arises called “youth bulge,” reflecting a disproportionate amount of young people with the virus compared with older populations.

The youth bulge also means that there are more adolescents accessing HIV clinics, leaving the clinics without enough doctors or space. Older adolescents often do not want to leave their clinic to go to an adult clinic where they fear facing more stigma.

Another project has been started to determine how to successfully transition HIV positive adolescents into the adult clinic setting.

“We hope this program builds that confidence and resilience and drive to be adherent so they have more self-efficacy, are more autonomous and are comfortable to go on to the adult setting,” Dow said.

With the positive outcomes of Sauti ya Vijana—including increased resilience, adherence and decreased viral loads—Dow and her colleagues are now working to design an HIV education program led by Sauti ya Vijana graduates.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.