With a Top 10 medical school and substantial pre-health advising office, Duke certainly has a stake in the field of medicine. A new program hopes to bring other disciplines into the conversation.

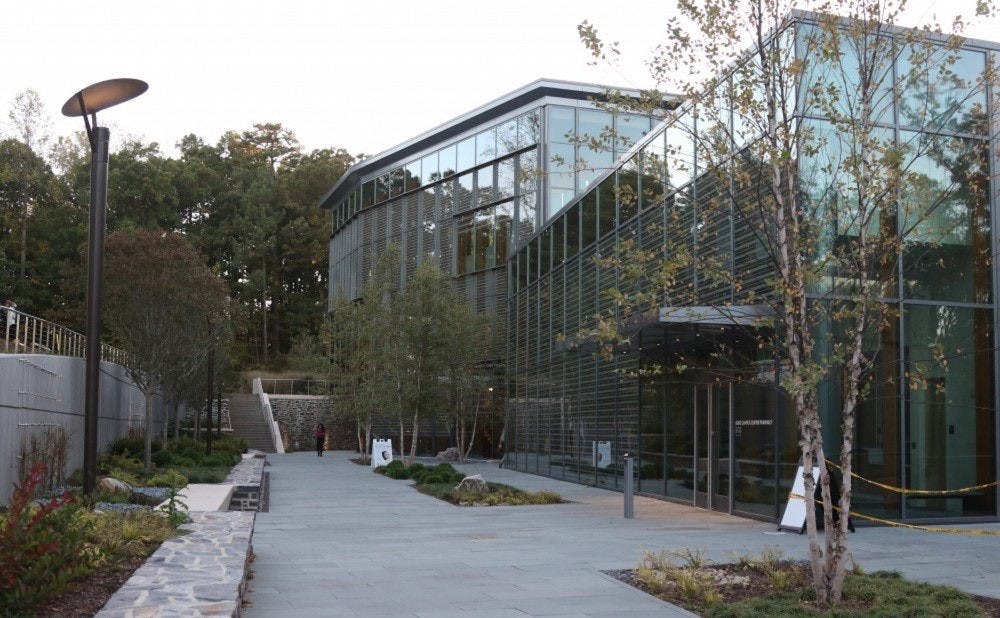

Narrative Medicine Mondays, a lunch group held at the Wellness Center, is one of the Health Humanities Lab's narrative medicine initiatives. The group meets monthly to analyze media — like books, podcasts and film — and engage in creative writing around a certain theme. Each month, the program introduces a new theme, like “Narratives of Childhood Health” and “Adolescence and Alice in Wonderland.”

Narrative medicine brings ideas and methodologies from the arts and humanities to the medical field to enrich the healing process for the patient by encouraging understanding between patient and physician. The discipline emphasizes the importance of stories, of listening deeply to others to understand a person’s bigger picture rather than just a series of data, to create more accurate and efficient outcomes.

Kat Berko, Trinity ‘18 and lab manager at the Health Humanities Lab, is involved in organizing and hosting sessions. Berko is a former staff writer for the Chronicle.

“With such an immense number of people interested or involved in healthcare on our campus, it's vital that they learn not just the technical aspects of medicine, but that they must practice that most basic yet complex building block of medicine — empathy,” Berko said. “And even if you're someone who has no interest in medicine whatsoever, narrative medicine is still relevant to your life because we all have bodies and minds to care for and doctors to visit. I don't think there's a person on this campus who can't benefit from narrative medicine.”

The program is led by professor of romance studies Deborah Jenson and student health director John Vaughn, who hope to work together to create a truly multidisciplinary, comprehensive program.

“This program is above all a chance to share openly, with a supportive community, on associations with the prompts provided, such that health and medicine become occasions for creative personal discovery and social integration around what is usually a tensely competitive, solitary, pre-health field,” Jenson said.

The practice of narrative medicine is centered around mutual storytelling. Examples include guiding physicians to encourage their patients to share their stories and listen with empathy and using the arts and humanities to help physicians identify human patterns which are often revealed through storytelling. Narrative medicine does not just employ literature; it incorporates visual arts, film and music too.

“For example, medical students or young doctors may read Leo Tolstoy's 'The Death of Ivan Ilyich' to enhance their understanding of what it means to be dying,” Berko said. “However, the texts used in narrative medicine do not have to be overtly related to medicine. The fundamental idea is that the study of narratives enhances a person's understanding of what it means to be human, which is not only a life skill but a vital characteristic for any medical professional to have.”

Humans tend to respond more intuitively to stories rather than statistics, and narrative medicine hopes to find the best ways to utilize storytelling to address both medical and social disparities.

Although reading narratives may not directly solve health inequities resulting from wealth disparities or institutional racism, it opens up a space to discusses these issues, Vaughn said. He stressed the importance of relying on facts before branching into narrative medicine.

"But reading a story, even a fictional one, about one patient and one doctor in a very specific and fraught encounter, will convey the meaning of that racial inequity in a way that is uniquely powerful and I would argue, more likely to stick with a person and lead to them being a more empathetic healthcare provider who is more likely to advocate for positive change, he said.

In addition to helping people understand health issues on a more human level, narrative medicine can produce more insightful and ethically grounded health care providers, Jenson said.

“Ultimately, in my opinion, patients also need to be welcomed to the practice of narrative health, gaining insight into their own stories, their own voices and choices," she said. "Problems in our medical culture are not one-way. Patients’ self-awareness, self-acceptance, and a willingness to efficiently translate experience to individuals on the other side of any health and suffering divide can improve outcomes."

This month’s session will focus on Alzheimer's and will be on Monday from 12 to 1:30 p.m. in the Wellness Center.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.