My dad recently told me that he had downloaded Grammarly, one of those softwares that checks the grammar of your emails for you. Up until this point, ensuring perfect grammar in my dad’s emails was my job. It was a tedious task, one that many first-generation Americans dutifully carry out at the request of their immigrant parents. I was hardly a fan of this chore. But what really frustrated me about this task was scrolling through the conversation to find that emails from my dad’s colleagues, subordinates and supervisors alike were littered with careless typos and grammatical transgressions worthy of Donald Trump’s tweets. It was clear that the effort my dad and I put into perfecting his emails was leaps-and-bounds beyond that of his (mostly white, American) colleagues.

Time after time, I’d ask my dad why he bothered to scrutinize every email when his colleagues clearly felt no such obligation. The response was always a variation on a theme that is common to immigrants (and indeed many people of color in America). As an Indian-American, my dad felt he had to constantly prove that he belonged in America’s professional class. Any slip-up would raise questions about his inherent value and qualifications. A typo by his white boss would hardly raise an eyebrow. A typo by my dad could be seen as proof of illiteracy.

And so my dad’s emails received more sets of eyes and much more attention than those he received in response: just one small way in which minorities have to work twice as hard to receive half the credit.

It’s because of this experience—this unnecessary burden that my dad has completely accepted for the 32 years since he moved to America as a graduate student—that the email sent by Megan Neely warning international students of the “unintended consequences” of not speaking English in public has so infuriated me. It’s why the blatantly discriminatory behavior of the two faculty members who wanted to blacklist students for having the gall to speak Chinese in public is so hurtful in my estimation.

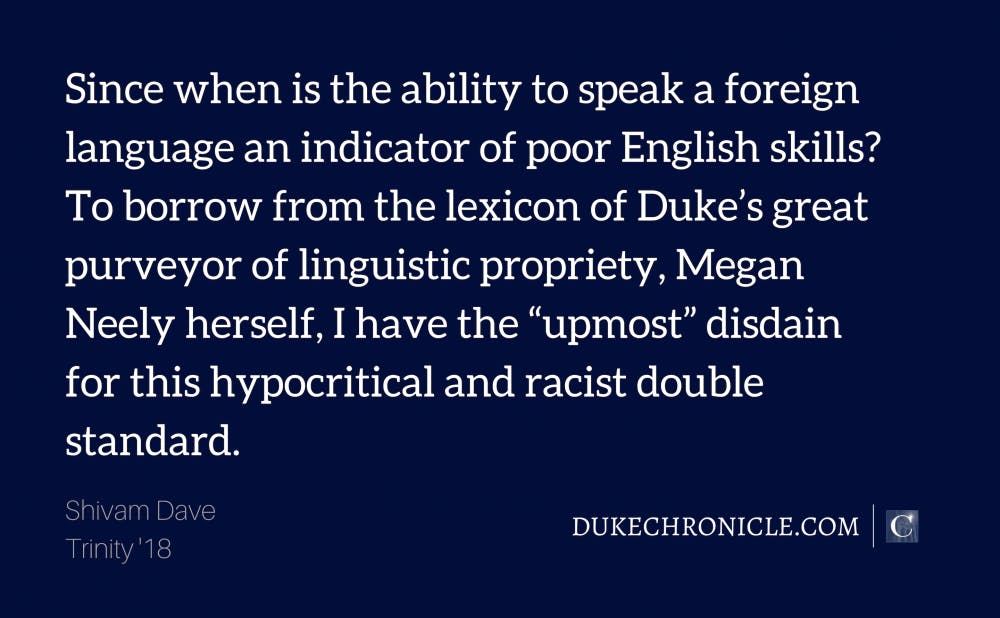

Thirty-two years ago, my dad was one of those graduate students, likely speaking Gujarati with his classmates who had arrived here on a student visa just like him. The idea that my dad and his friends, or the students mentioned in Neely’s email, should have taken that time to “improve their English” is patently absurd because no such requirement has ever been placed on white Americans, regardless of their demonstrated English proficiency or lack thereof. Indeed, the assumption that these students need to improve their English is a baseless one. Since when is the ability to speak a foreign language an indicator of poor English skills? To borrow from the lexicon of Duke’s great purveyor of linguistic propriety, Megan Neely herself, I have the “upmost” disdain for this hypocritical and racist double standard.

The problems with Neely’s email go further than this faux concern for professionalism and politeness—the two being ill-defined vague concepts which can be used to paint minorities as less qualified, much in the same way that Harvard University rated Asian-Americans as lacking in “personality traits” according to a lawsuit against the university. There is also the problem of upsetting but unsurprising entitlement. To say it is impolite to have a conversation that not everyone can understand implies that at least at Hock Plaza, English speakers are entitled to understand every conversation, regardless of how irrelevant those individuals may be. The very conversations of non-white individuals are thus colonized. I hardly need to mention how unlikely it is that Megan Neely and her two concerned colleagues have shown such multilingual courtesy when traveling outside the States.

And then there is the ignorance of the immeasurable worth of one’s native language that lies subtly underneath this incident. As I get older and spend less time at home, I can feel my mother tongue slipping away from me. I rarely have the opportunity to converse in Gujarati and I worry that if this trend continues, I won’t have enough of a grasp on the language to share it with my future children. The inextricable connection of my language to my culture—to my identity—makes this a terrifying prospect. And this incident is another reminder of the inhospitable, and at times hostile, environment in which diverse Americans aim to preserve their non-dominant cultures. Is it that far a leap for a young student, who has been told to leave their language at the door when entering a student lounge, to feel that passing that language on to the next generation might actually disadvantage them? Is it not an impetus for cultural erasure that “whitened” names lead to better job prospects, implying that foreign names rooted in foreign languages and cultures are professional barriers? Does it not seem concerning that the assimilationist rhetoric of Jerry Hough, which was dismissed by some as the rantings of an older generation, is replicated still today by Duke faculty?

At this point, I care little about the follow-up to the incident because I remain pessimistic that the sentiment that precipitated Neely’s email can be changed or addressed, especially since it is likely present far beyond the Duke Biostatistics and Bioinformatics department. But I do want to make it clear how absurdly foolish and ignorant that sentiment is, and express my support to the students it was directed toward. To them I say: say whatever you’d like to say, wherever, whenever, and in whatsoever way you’d like to. If the desire of some faculty members is to have you replicate the professional behavior of White America, that’s a pretty good way to start.

Shivam Dave is a Duke alum, Trinity ‘18.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.