CHAPEL HILL, N.C.—In August, UNC protesters toppled Silent Sam. Monday, protesters took to the streets after university leadership said they have plans to put it back up.

Protesters at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gathered Monday night to rally against the reinstallation of the Silent Sam statue in a new, stand-alone building. Hours before, Chancellor Carol Folt and the Board of Trustees announced that the statue of Silent Sam, which had since been held in storage, would return to campus.

Folt and Provost Robert Blouin wrote in a message to students that the monument would be put in a new “free-standing building with state-of-the-art security.” Its cost? An estimated $5.3 million to construct, plus $800,000 per year to maintain the building.

The protesters did not take the news kindly.

“UNC prides itself on diversity and inclusion, and having that statue on this campus obviously shows that it doesn’t stand for diversity and inclusion,” said Leeza Mason, a UNC senior at the protest. “That statue stands for racism, the confederacy and basically keeping slavery on this campus.”

The protest began at 7:00 p.m. at the Peace and Justice Plaza on Franklin Street with Jewish leaders lighting the menorah for the second night of Hanukkah.

Protesters gave speeches for approximately an hour, criticizing the administration and UNC's Board of Trustees. Duke senior Sabriyya Pate attended the protest after hearing about Folt’s recommendation from friends at UNC.

“Commemorating white supremacy at any university is wrong and I think it’s really important today, especially because Duke is so focused with what’s happening with the Carr Building—which is progress—but there is much more to be done in terms of holding our institutions accountable to address white supremacy and racism,” she said.

Monday’s protest was not UNC senior Savannah Patterson’s first against Silent Sam.

“I have a lot of privilege as a white person, and I feel like speaking out is all I can do with my privilege,” she said.

During the speeches, a man repeatedly interrupted the speakers, screaming. He was met with a chorus of yelling, including calls of “racist, go home!"

Those weren’t the only chants intermingled throughout the speeches. Most of them stressed the power of banding together: “Ain’t no power like the power of the people, because the power of the people don’t stop!”

'Whose streets? Our streets!'

At around 8:00 p.m., the protesters began marching down Franklin Street. Chants filled the air.

As she walked down the street, UNC senior Aja Crayton expressed why she was taking part in the protest instead of studying.

“It’s finals time, but this is important to me because I’m feeling uncomfortable by the statue being up, people who look like me are feeling uncomfortable by the statue being up,” she said.

Marching protesters proudly declared that “this is what democracy looks like.” But the shouts of as “cops and Klan go hand in hand” bothered Nate Priebe, a UNC sophomore.

“I support this movement and then, I hear people say ‘f*** the police’ and they’re talking about the counter-protesters, and people say ‘snap their necks’ to each other—they’re not chanting that, but I think that’s a really bad sign for what’s to come,” he said.

The protesters moved towards the pedestal where the statue previously stood. There was one metal barricade directly around the pedestal and another forming a wide perimeter to keep protesters away. Roughly 20 police officers were positioned in the area, riot shields and helmets leaned up against the inner fence.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Waving their banners and signs, protesters began pushing against the barricade. Police pushed back.

“Who do you protect?" the protesters chanted at the police. "Who do you serve?”

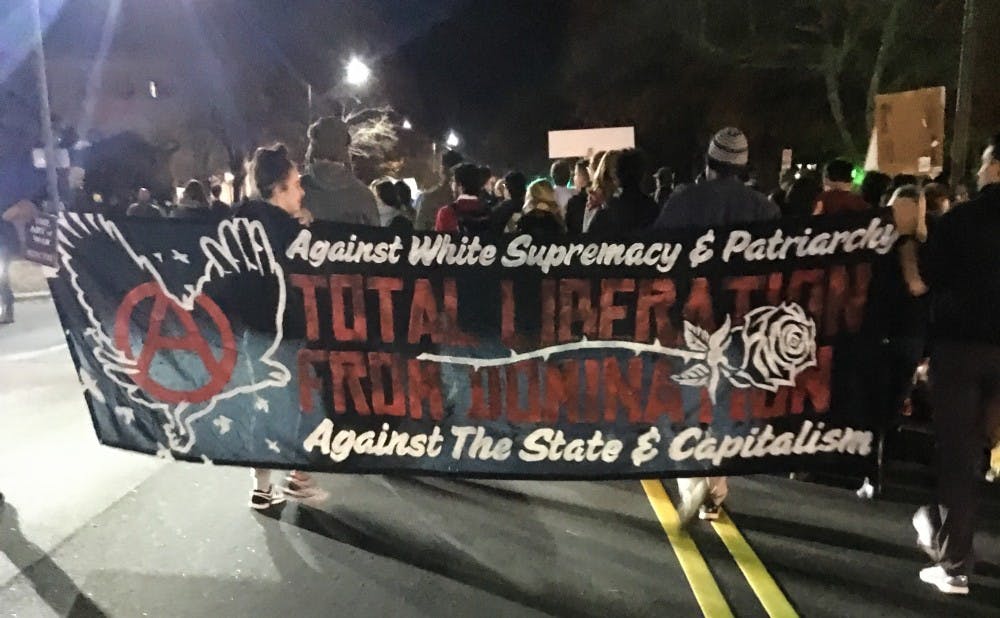

As protesters continued to push against the fence, police officers pulled away a banner that read “total liberation from domination” from the crowd. Hostility between protesters and police cooled off as protesters began walking away from the barricade.

The protest moved to South Building, which houses key administrative offices for the university. There, protesters linked arms.

“It is our duty to fight for our freedom,” the chant began. “It is our duty to win. We must love and protect each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains.”

History of Silent Sam

Silent Sam had stood on campus since 1913. At the Confederate monument’s dedication, Julian Carr—a “virulent white supremacist” whose name was just stripped from what is now dubbed the Classroom Building on Duke’s East Campus—boasted about “horsewhipp[ing] a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds.”

The Silent Sam monument was first defiled in 1968, but came under more scrutiny after a UNC history graduate student unearthed the text of Carr’s speech and published it in a Daily Tar Heel letter to the editor.

Over time, attention on the monument and its history grew. In the wake of the "Unite the Right" rally in Charlottesville, Va., in which white nationalists and counter-protesters clashed about a statue of Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army.

Just after the Charlottesville rally, Chapel Hill Mayor Pam Hemminger asked the university to remove the statue. Folt said it would be best for it to be moved, but said the university would follow the law. Folt faced protests, which came to a head when Maya Little, a history doctoral student at UNC, splattered red paint and blood on the monument in April 2018. Four months later, Silent Sam was pulled down by protesters.

Folt and Blouin wrote that they would prefer to put the statue somewhere off campus, but North Carolina law stands in their way. The 2015 Cultural History Artifact and Patriotism Act barred the permanent removal of any “object of remembrance” without the approval of the North Carolina Legislature.

Managing Editor 2018-19, 2019-2020 Features & Investigations Editor

A member of the class of 2020 hailing from San Mateo, Calif., Ben is The Chronicle's Towerview Editor and Investigations Editor. Outside of the Chronicle, he is a public policy major working towards a journalism certificate, has interned at the Tampa Bay Times and NBC News and frequents Pitchforks.

Jake Satisky was the Editor-in-Chief for Volume 115 of The Chronicle.