Banners in front of the Brodhead Center scream at passing students to “VOTE EARLY.” My Facebook feed has been flooded with political ads encouraging people to cast their ballots for this candidate or that candidate. Even celebrities, from Amy Schumer to Rihanna to Taylor Swift, have publicly endorsed civic participation at the polls.

I commend the effort.This election could be a huge turning point. If Democrats win the majority, they could start taking down President Trump. If Republicans manage to stay in control, they could further their legislative agenda. So encouraging everyone to vote is, of course, a good thing. The ability to vote—to have some say in the future of our country—is an American’s most important and impactful political right. But I think it’s also worth talking about the flip side. When we ask everyone to cast a ballot, there’s bound to be some cases of ignorant voting, which begs the question: is uninformed voting better than not voting at all?

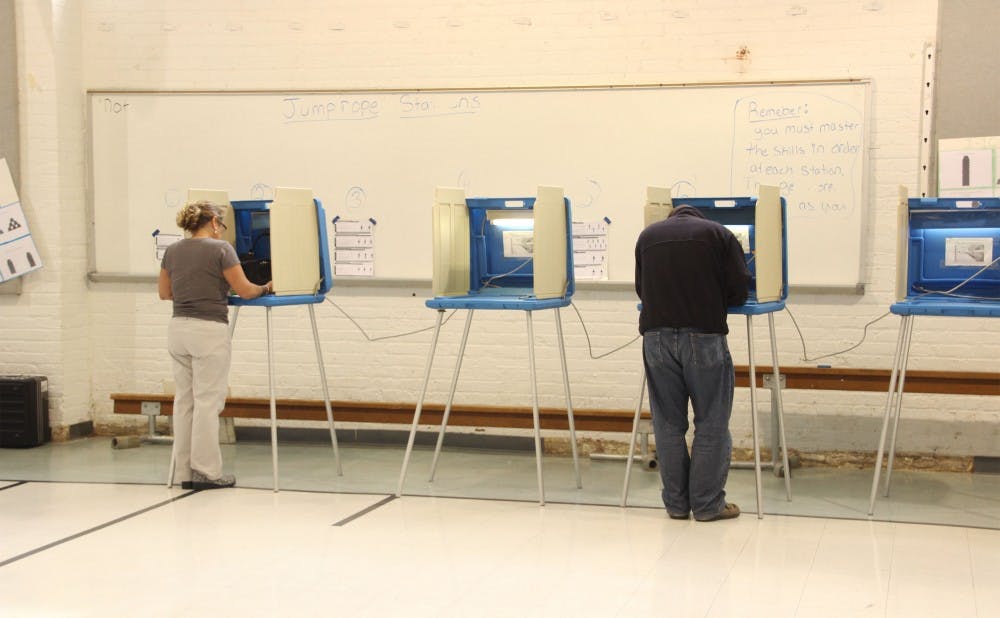

Ignorant voting is not unusual. The other day I caught my friend walking out of the Brodhead Center with an “I voted” sticker on his shirt. Curious about the race in North Carolina (I’m voting absentee), I asked about who the incumbents and non-incumbents were. “Honestly I didn’t know half the names on the ballot. I just circled some random ones from my party.” His response didn’t surprise me: I’m guilty of doing the same thing. Last semester, I felt compelled to vote in Durham’s local elections even though I knew very little about the candidates, and even less about how a local government functions. Much of America is in the same boat when it comes to the most basic information about our nation’s political system. More than a third of Americans can’t name any of the rights guaranteed under the First Amendment, and only a quarter can name all three branches of government. Regardless of whether you know our constitutional rights or structure of the government, you are allowed—you are encouraged—to vote.

The ignorant voter poses a danger. Those who are misinformed sometimes support a policy that is contradictory to their beliefs. For instance, many people overestimate how much of the United States’ federal budget is allocated towards foreign aid, on average estimating it to be 10 percent. In reality, it’s only about one percent of the budget. At the same time, we underestimate how much goes to entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security. That’s why many Americans, when asked how to solve the country’s debt crisis, believe in just cutting discretionary spending without touching entitlements or raising taxes. “That delusion makes it very hard to do budget policy in a rational way,” says George Mason University Professor of Law Ilya Somin.

Unfortunately, even when people do seek to inform themselves, they do a poor job of it. Instead of conducting objective research, they gravitate towards information that confirms their existing beliefs, and that further entrenches them along party lines. Any evidence supporting the other side is a product of ignorance, but that same accusation could never be true of their own party. People are more biased than they like to admit. When I participated in my state’s Democratic caucus in 2016, I was in high school, and my high school self didn’t pay nearly enough attention to political happenings. Consequently, my vote was strongly influenced by my dad, who was spewing facts from MSNBC in support of his preferred candidate right before the caucus. When people asked who I voted for, I couldn’t properly rationalize it. I knew nothing beyond their party lines and their stances on a few big issues based on my dad’s pre-caucus briefings. What I lacked was a wide enough perspective of the political landscape to explain how my candidate’s platform supported my own values and played into the broader policies of the nation.

To be clear, I’m not trying to discourage voting. Rather, I want to change the message from “get out there and vote” to “do your research and vote.” You don’t have to understand the intricacies of Congress or every single policy at play. Simply know who the candidates are: what do they support? What do they believe in? What are their values? When you go to the polls this November, know that the decision you make will impact the lives of everyone else. Voting is a right and a privilege, but it’s also a luxury. Careless, misinformed voting is just as bad, if not worse, than not voting at all.

Alicia Sun is a Trinity junior. Her column usually runs on alternate Wednesdays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.