In front of then-Provost Peter Lange was a wide open, flat field.

He was looking at a plot of more than 20 acres in the city of Kunshan, an hour’s trip on a high-speed train from Shanghai. His Chinese hosts could point to a part of the field where there may be a lake one day, but the only structure was a billboard saying something to the effect of “Welcome Duke University to your home of the future!”

Half a world away from home and Duke, the middle-aged academic was looking at the physical blank slate on which he and his colleagues would, over the course of the next decade, build an experimental university from scratch. In the midst of China, Duke would attempt to establish itself as a truly global academic power in the medium-sized city that had attached itself to the American institution in hopes of reaping the benefits of its brand and intellectual product.

What started off as a venture by Duke’s business school soon snowballed into a full-blown college called Duke Kunshan University, which started with offering master’s degrees and was built from the top down as an undergraduate program was added, beginning this fall. DKU is half a world away from Durham. It’s a liberal arts college offering majors in “Global China Studies” and data science. It’s one of a handful of such ambitious American educational outposts in the region.

Other American schools, like New York University and Yale University, had established undergraduate programs in the region. Yale-NUS opened in Singapore in 2011, and NYU-Shanghai opened in September 2013 as the first accredited independent school in China.

But when DKU opened its doors to its first students in August 2014, and to a full undergraduate program four years later, it was only the second American school in the area that offered a four-year degree with the home institution’s name attached. The students who would one day become the school’s first undergraduate class were in primary school when the idea was first formed.

But things did not just fall into place. It took a decade and millions of dollars.

Blair Sheppard had been involved with Duke’s Fuqua School of Business for more than 25 years when the dean’s position became of interest in 2006.

After spending two months observing Fuqua and ruminating on ways to move the school forward, he decided the school needed to establish firm connections in five key areas of the world, with China being foremost among them.

It was a sweeping, international plan. In January 2007, he was announced as Fuqua’s new dean.

A meeting in Venice

In the summer of 2007, Sheppard assumed the role from outgoing Dean Douglas Breeden at a gala in Venice. In a meal with Lange and then-president Richard Brodhead, he told them specifics of his developing plan to establish a physical presence for the business school in China. He said that he had visited the country twice by then, scouting out locations and possible partnerships.

That meeting, Lange said, was when they made the decision to look into the idea of starting a venture in China. Sheppard decided there were three arguments for Fuqua to establish a campus in China: a competitive one, an innovative one and an academic one.

The competitive argument was clear—previous expansion of international programs had helped the school get a leg up on competitors, and a more dramatic expansion should then produce more dramatic results.

The innovative argument was that while other schools had done a good job of partnering up around the world and everyone had allies, few had taken the step of being permanently present.

The academic rationale was Duke’s responsibility to educate the next leaders of the world, which meant creating opportunities for their students to develop more than an American lens on global affairs.

It quickly became clear, however, that the Chinese counterpart would not be satisfied with just a smattering of business school programs, Sheppard said. They wanted a Western-style university, complete with an undergraduate liberal arts degree. The riskier aspects—particularly that the degrees awarded would be Duke degrees—were also what made the venture so unique.

When the idea of launching an undergraduate program with Duke’s degrees was brought before Duke’s faculty, they poked holes in the project for years before it went to a vote.

Lawrence Zelenak, Pamela B. Gann professor of law, was a member of the Academic Council’s Executive Committee when the idea was in its formative stages. An early and steadfast critic of the plan, Zelenak disdained the idea of franchising higher education and Duke’s brand and was concerned the project would become a money pit for the University.

“Maybe most of all, I was concerned that if you were going to do this any place, China may be one of the riskiest places to do it because the authoritarian, repressive nature of the regime is such that it is fundamentally inconsistent with the freedom and clarity that is crucial to a university,” Zelenak said.

He was also fearful of the “boiled frog problem,” referring to the idea that if you put a frog in a hot pot of water, it will jump out, but if you slowly turn up the heat, it will remain in the pot. For Duke, this meant that he was concerned that the guarantees of academic freedom may slowly disappear, until eventually the project existed in a form that no one would have consented to in the beginning. In the same vein was his concern for the “sum-cost fallacy.”

“There would be a tendency to stay there to justify what we had already invested,” Zelenak explained. “And of course there’s reputational concern there too. Apart from money down the drain, it would be embarrassing to leave.”

Lange noted that, even in the early stages, the conversations hovered around academic freedom.

“Obviously academic freedom was always a preeminent issue, and we paid close attention to the conditions under which the university could be founded and operate,” he said.

But for Steffen Bass, professor of physics and a member of the Academic Council’s Executive Committee at the time, it was the risk that made the argument for academic freedom so compelling.

Running into problems with academic freedom and freedom of expression is not a question of “if” for DKU, he said, but a question of “when.” Although there have been substantive agreements made regarding freedom on campus, ultimately the faculty and students of DKU exist in a country that does not guarantee those rights, Bass said, and it’s easy for the conversations that occur in the safety of classrooms to turn into public actions.

"[There’s a] big difference between what happens in a classroom and what happens out on the street,” Bass said. “So at some point, somebody is going to do something stupid and there will be tension with the Chinese law. And Duke will not be able to fully protect whoever did something stupid.”

But that is not necessarily a bad thing, the nuclear physicist argued. The long-term benefits of DKU outweigh these individualistic concerns for him.

Lange noted the benefits of Duke’s establishment of a university in Kunshan were that it would broaden Duke’s international strategy, bolster Duke’s reputation and establish a strong presence in a country that is viewed as highly dynamic. For China, it would be a welcome addition of a world-class university to improve their higher education offerings.

Joshua Sosin, associate professor of Classical Studies at Duke, encountered DKU early through serving on an academic advisory committee to Lange. He pointed to Duke’s other permanent and physical international venture—a medical school in Singapore—that is credited for introducing the concept of flipped-class teaching in the sciences as an example of the types of unexpected innovation he hopes to see come out of the university.

For Carlos Rojas, professor of Asian and Middle Eastern studies who served on Duke’s China Faculty Council and helped shape the humanities research offerings at DKU, the impact will be largely symbolic. Although it can set the precedent for other collaborative institutions, DKU is not going to fundamentally change the paradigms of higher education.

“I think it’s a really interesting and bold experiment,” Rojas said. “There’s a lot of potential benefits, if everything goes smoothly.”

The Swissotel era and Duke's earliest roots

Although faculty members like Sosin who were involved in the faculty governance caught the first glimpse of the plan on paper, people like Marc Deshusses got the first full taste of it. He taught there during the second quarter of DKU’s first semester in August 2014.

For Deshusses, professor of civil and environmental engineering, coming in for the second half of the semester meant that he narrowly missed the project’s Swissotel era. Before the campus was complete enough to hold classes, the operation was based out of the five-star Swissotel in Kunshan. This meant that faculty and students were eating, sleeping and teaching all in the hotel for the first quarter, he explained.

By the time Deshusses arrived, operations had moved on to campus, but the circumstances had barely changed. Because construction on other parts of the campus was still incomplete, they resided in DKU’s conference center. They slept on the third floor, taught on the first floor and ate in the cafeteria.

For Deshusses, teaching the inaugural semester at DKU under its quarter system meant he could spend a month there teaching a course on bioenergy and establishing research connections in Shanghai, then let his post-doctoral student wrap up the course.

Teaching at DKU came with quirks. Deshusses taught with two boards, one with the engineering material he was teaching and another with complex English words he didn’t expect the students to know.

“When you see a little group developing and you see them get their little electronic translators trying to find the meaning of a word,” he explained. ‘Then it’s when you pause and translate.”

DKU was not Duke’s first foray into the region. In 2005, Duke first planted roots in East Asia, signing a formal agreement with the National University of Singapore to establish a graduate-level medical school there.

In November 2006, Academic Council voted unanimously to make the degrees offered at the medical school truly joint between Duke and its partner institution, through putting both schools’ names on the degrees. After a successful start, Duke and the Singaporean government have extended the partnership twice. Under the agreement, Duke-NUS is modeled after the Duke University Medical School’s curriculum but is a part of the National University of Singapore System. Sheppard pointed to Duke-NUS as a model he looked to in the early days as a proof of the concept.

It wasn’t long, however, before the business school’s plans started to look significantly different than the outpost Duke had established in Singapore. It was not clearly demarcated when DKU started being viewed as bigger than a business school venture, as the parties involved had different plans for the project. Sheppard said he started to see what the Chinese counterpart was getting after during negotiations in his second visit to Kunshan in June 2007. In a 2008 trip to Kunshan with Sheppard, Lange said their intentions were becoming clear.

“At this point, of course, it’s all still expected to be a business school venture,” Lange said. “But on that trip, it also started to become evident that the city of Kunshan was looking on it not just as a business school venture but as something that would eventually also be on a bigger scale. So we had to start discussing it in that context.”

For the second negotiations meeting, Sheppard said that he and his wife flew out to Kunshan and had a Duke Fuqua faculty member act as the translator. Sheppard was talking about what they wanted from business school programs in Kunshan, but the Chinese were discussing what they wanted a full university with a liberal arts undergraduate program to look like.

“I looked at them and said, ‘I just don’t know if that’s possible, because I’m here representing the business school and this is going to be challenging, so a university is going to be really hard,’” he recalled.

Despite Duke offering numerous other solutions, the Chinese were steadfast in wanting a full university with an undergraduate degree program.

“Honestly, if you asked me at the time what the chances are it was going to happen, I would have said zero,” Sheppard said.

Bass said it was clear that they would have to start an undergraduate program to get the support for the graduate-level programs they wanted.

“The way this was unfortunately oversold was that Duke would have virtually no risk and no expenses because [the city of] Kunshan would put this wonderful campus in place and Duke would only have to send over the people and that was it,” he said. “Clearly, things didn’t happen that way.”

One of the first and critical steps in the process was choosing the city of Kunshan as a partner with financial responsibilities, Sheppard said. Agreements with the city later limited the amount of financial risk Duke faced, with the city agreeing to cap Duke’s input at $5 million per year. Everything else would fall to Kunshan, which was also providing the land and constructing the buildings as a gift.

But Chinese law required that Duke partner with a domestic institution to ensure Chinese interests in the academic programs. When Duke’s first intended partner Shanghai Jiao Tong University, a prestigious university in Shanghai, backed out because Duke wanted to build the school in Kunshan due to the financial advantages, Duke landed with Wuhan University.

Sheppard pinpointed Wuhan agreeing to sponsor Duke and take a backseat on shaping the program as the turning point for when he thought the whole project was going to happen.

In December 2010, almost exactly a year after the faculty were first formally briefed on the administration’s intent to explore the project, Academic Council was discussing the framework under which it wanted to approach undergraduate education at DKU, according to archived transcripts of their meetings.

Greg Jones, Lange’s vice provost and one of the leaders of negotiations with the Chinese, briefed the Council on the Kunshan government’s commitment to finance the construction of the 750,000-square foot campus at the equivalent U.S. cost of $90 million, he said. Duke, in turn, would need to invest approximately $11 million in the Phase 1 design and development.

“We think it’s actually a relatively modest investment in terms of the overall impact that establishing this presence in Kunshan will have for Duke’s presence and our identity as a global university,” Jones told the Council.

Costs were also mounting for the city of Kunshan. As parts of the construction were not up to Duke’s standards, it fell on the city to have them rebuilt, sometimes three or four times. It was enough to make them gulp, Sheppard said, but they did not pull out.

In the March 2011 Academic Council meeting, faculty were told that Duke would be on the line for $37 million across six years for the venture, with $10 million coming from outside sources, according to transcripts of the meeting.

At that point, the school was slated to open in July 2012. It would not open its doors until two years later.

“[Negotiating with China] was actually easier than the challenges of Duke,” Sheppard said. “And to be fair, part of the reason is that we kind of surprised everybody.”

‘A move forward’

Brodhead stood in front of Academic Council and urged members to “make no little plans.”

This vote in November 2016 was on whether Duke faculty would approve the creation of an undergraduate degree program at DKU.

The faculty governance body had been fiercely debating the specific issue of an undergraduate degree for months and the concept of DKU for years at this point. Sosin joked that from his view, it seemed they had almost run out of faculty members willing to serve on committees to investigate it further.

“By the time we were done, it was like, ‘Oh my god, this again,’” he joked.

Brodhead didn’t mince words, acknowledging the various sides of the debate before making a final push for the program.

“A moment when nations and cultures are beginning to divest from the idea of the international order seems to me the time that needs something like the DKU undergraduate program more than ever,” Brodhead said. “That’s finally what you would be creating here.”

A stretch of impassioned debate ensued. William Johnson, professor of Classical Studies, warned faculty against viewing the endeavor as a “paternalistic enterprise.” He taught at DKU the first semester it offered classes and reminded the faculty that the exchange is not a one-way street. He told his colleagues they have a lot to learn from China, jokingly noting that he had learned more about democracy from discussing it with Chinese students than anyone in the United States.

Charles Becker, research professor of economics, pushed the faculty to consider the opportunity costs of the effort that would be expended for such a program. Earl Dowell, William Holland Hall professor of mechanical engineering, questioned whether Duke was the best-suited institution for such a task.

“There are all these uncertainties, but for the moment, I’m willing to concede that you have a wonderful curriculum created by some very able faculty,” Dowell said. “Certainly there’s no evidence as of yet that the Chinese are squeezing us with respect to freedom of speech, although they would be very foolish to do so before we’re fully committed.”

Alexander Rosenberg, R. Taylor Cole professor of philosophy, toyed with the sensitive topic of academic freedom in the new experiment, saying that the more he thought about the issues associated with it in China, the more he thought Duke should do it. It would be, in his eyes, a gut check for the power of faculty governance within Duke—could the faculty really pull the plug later if the venture became too much of a drain?

Johnson, the classical studies professor, framed the vote in the larger context of the University’s history.

“I think when a historian writes the history of Duke University 100 years, 200 years from now, this vote, if it goes forward, could be the biggest part of the story of our University,” Johnson said.

The resolution passed by a vote of 57 to 18, to the Council’s applause.

The proposal would still have to receive the stamp of approval from the Board of Trustees. Sally Kornbluth, the current provost who replaced Lange after his retirement, expressed measured excitement after the vote.

“I feel like this is a wonderful thing for Duke to be doing, and I’m happy that there was a great dialogue over a very long number of years. We have a positive vote that endorses the move forward, but I’m also mindful of folks… raising the importance of review going forward and keeping a close eye on how progress is going,” she said.

Lange stepped down from the provost role after a 15-year tenure just as Duke was gearing up for the negotiations to reach a decision on the undergraduate degree. He remained on the venture’s board for a while longer as Kornbluth transitioned into the role. Two years before Lange left his position, Sheppard had been replaced as dean of Fuqua by Bill Boulding in 2011.

‘Where we anticipated we would be’

In Summer 2018, more than a year after the undergraduate degree program received the nod of approval from Duke’s administration, it became a reality.

The shape-shifting vision of what DKU would look like as a full-grown institution has finally settled into specific expectations. Duke built a university from the top down—starting with research centers and master’s programs before filling in the gaping blank of designing the undergraduate program.

The inaugural class of 250 students that was recently admitted is expected to expand to average class sizes of around 500 during the next few years. The curriculum the students will take is rooted in interdisciplinary majors, as DKU is not organized into departments. The students will visit Duke’s Durham campus for a semester and a summer. When they graduate, they will receive Duke degrees which denote they are from DKU.

The inaugural cohort of faculty for the undergraduate program is in the process of shifting their academic lives, in most cases, across continents.

For Bowdoin Professor Scott MacEachern, who had been at Bowdoin for the last 23 years, the transition means figuring out what to do with the thousands of books in his office, he joked when the faculty were at Duke for a week of workshops and meetings in the spring.

For Peter Pickl, a young German physics professor who has spent all but a few years of his life in Munich, the change is a chance to try something new. In March, Pickl said he was planning the move to China in just a couple of weeks.

Brodhead, who retired from the Duke presidency last year, was named an honorary chancellor of DKU. He wrote in an email in Spring 2018 that he has committed to having some form of teaching presence at DKU, though the details had not been hammered out.

Academic freedom in China is still a hot-button issue for the University—and it’s already seen a small test. In the spring of 2017, Duke professor Prasenjit Duara nearly had to call off a conference he had planned at DKU because the Ministry of Education dragged its feet with approving the plans. Duara said at the time that he didn’t view it as a violation of academic freedom, but acknowledged concerns about the de facto issues that can rise through the “gentleman’s agreement” of an approval process.

“There have obviously been plenty of ups and downs and challenges, but we’re pretty much where we anticipated we would be at this point,” Lange said. “Maybe a year later than we might have hoped.”

'Possibilities for exploration are endless'

More than a decade after the idea was first hatched, DKU is beginning to take on its full form.

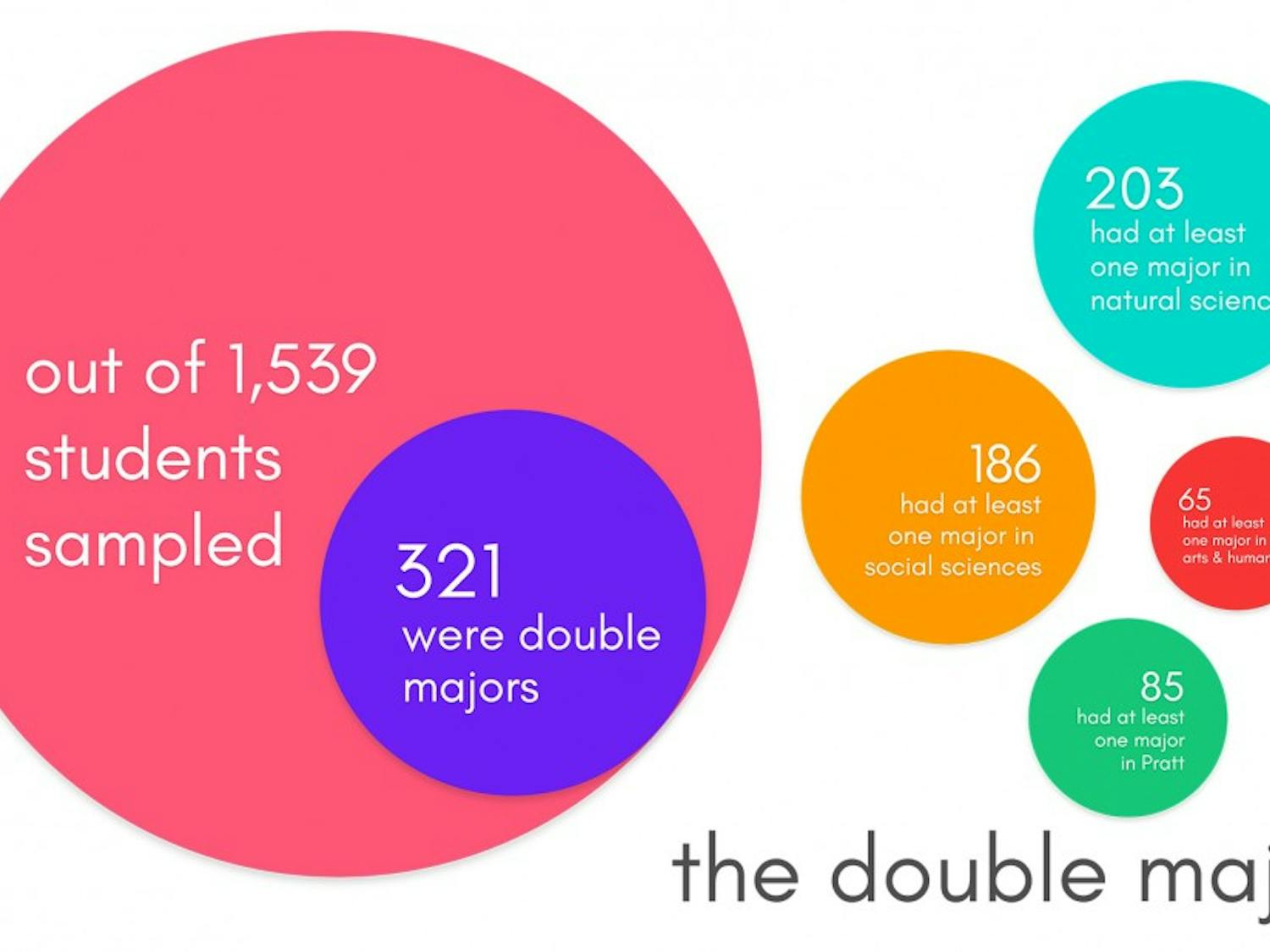

More than 250 undergraduates from 27 countries—with a large portion from China or the United States—are weeks into their first term on the Kunshan campus, part of the school’s first undergraduate class.

As of Fall 2018, the school offers 15 majors—including material science/physics, media and arts, ethics and leadership, political economy and U.S. studies. With a focus on interdisciplinary learning, undergraduate students declare their major in the second year. A focus of the curriculum is fluency in Chinese and English, meaning students are required to take multiple language classes.

The school aims to recruit 50 to 65 percent of each undergraduate class from China, and the rest from across the world. The school offers some merit scholarships and some need-based aid as well. Tuition, in U.S. dollars, is $26,500 per semester for the 2018-19 academic year, and the total cost of attendance for the year is $65,245 for students who are not from China. A 232-page undergraduate bulletin describes the program in detail.

The faculty are divided into divisional areas of knowledge—natural sciences, arts and humanities and social sciences. Instead of semesters, classes are organized around intensive seven-week terms.

For first-year Amy Westerhoff, DKU's "mix of cultures and experiences" was a feature that stood out and she couldn't pass up, she wrote in an email.

"It has definitely been tough understanding and navigating a foreign culture. I’ve had moments of success in daily activities, such as in navigating several bus routes," she wrote in August. "However, I have encountered difficulties in communication (I almost ordered eight park tickets instead of one) and in using Chinese apps and my new Chinese phone."

There are some strains that come with the adjustments. As a vegetarian, it can be difficult to find dishes in the cafeteria, and classes and clubs are no longer her only worry.

"On top of the typical college worries, I have and will encounter many language and culture difficulties," Westerhoff wrote. "On the other hand, this has benefits that will prepare me for cross-culture communication in the future. In addition, the people and the city of Kunshan are exciting and the possibilities for exploration are endless."