The composition of faculty rank is radically changing at Duke and at some of its peers.

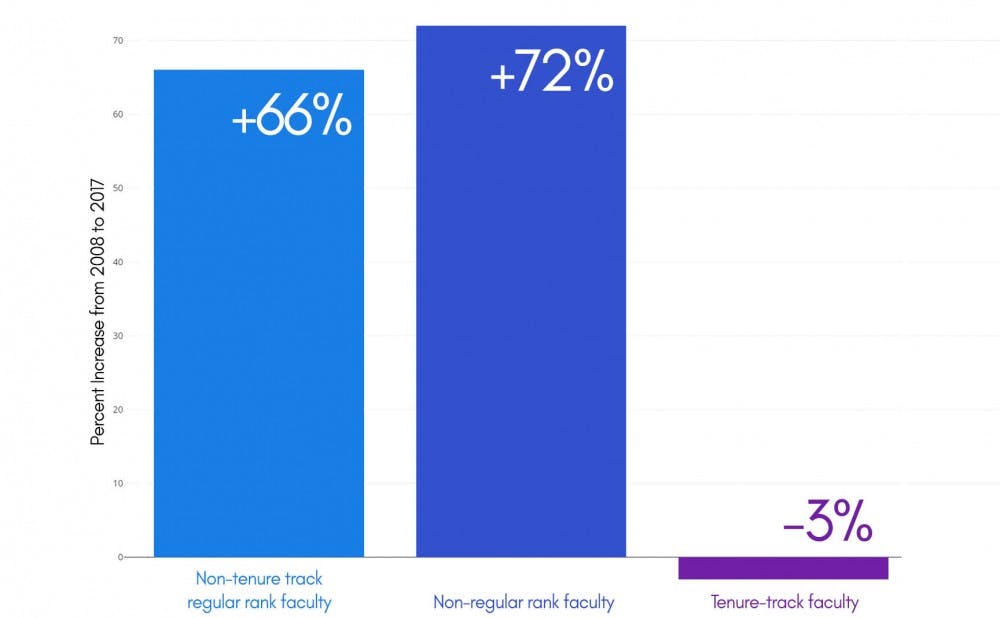

From 2008 to 2017, the number of tenure track faculty at Duke declined by three percent. In contrast, the number of non-tenure track regular rank faculty grew by 66 percent. Non-regular rank faculty increased by 72 percent.

This was not an intentional change driven by an overarching strategy, according to a new report presented to Academic Council last week. The pressures—including tightened budgets and increased master’s programs—that drove the shift towards non-tenured faculty are not going away. Several new master’s programs were approved by Duke last year.

“The faculty mix at Duke has unambiguously shifted away from tenure-track faculty toward non-tenure track regular rank faculty, and especially toward non-regular rank faculty,” the report states.

The background

After a task force on faculty diversity in 2015 noticed that there appeared to be a shift in the rank distribution of non-regular rank faculty, said Gavan Fitzsimons, Edward S. & Rose K. Donnell professor of marketing and psychology. Fitzsimons was picked to chair the follow-up ad-hoc committee, which sought to find out if there was a change in the rank distribution.

At Duke, there are three categories of faculty rank: tenure track professors, non-tenure track but regular rank, and non-regular rank.

Tenure track professors are assistant and associate professors, or full professors who have already gained tenure. They typically split their time between research and teaching, and some take on service to the University.

Non-tenure track but regular rank professors are ones who fall within the scope of regular rank, but not in tenure-track positions. These are professors of the practice and research faculty. Non-regular rank faculty are, for example, adjunct faculty, who are hired on short-term contracts and paid on a per-class basis.

If it sounds complicated, that's because it is.

Fitzsimons explained that most other schools don’t distinguish between regular rank and non-tenure track regular rank faculty, further complicating Duke’s academic alphabet soup. We'll spare you further explanation of the titles associated with each rank, because according to the report produced by Fitzsimon’s committee, Duke uses almost 60 different ones.

Here’s what their eight-page report says: the faculty distribution at Duke has shifted dramatically in recent years toward non-tenure track faculty.

The numbers

Across the University, the number of tenure track faculty has declined slightly from 2008 to 2017 as the number of non-tenure track regular rank and non-regular rank professors has risen steeply.

According to the report, the committee is “convinced that this shift in faculty rank is real, with [tenure track] faculty numbers not growing, while [non-tenure track regular rank] faculty and [non-regular rank] faculty numbers have grown substantially.”

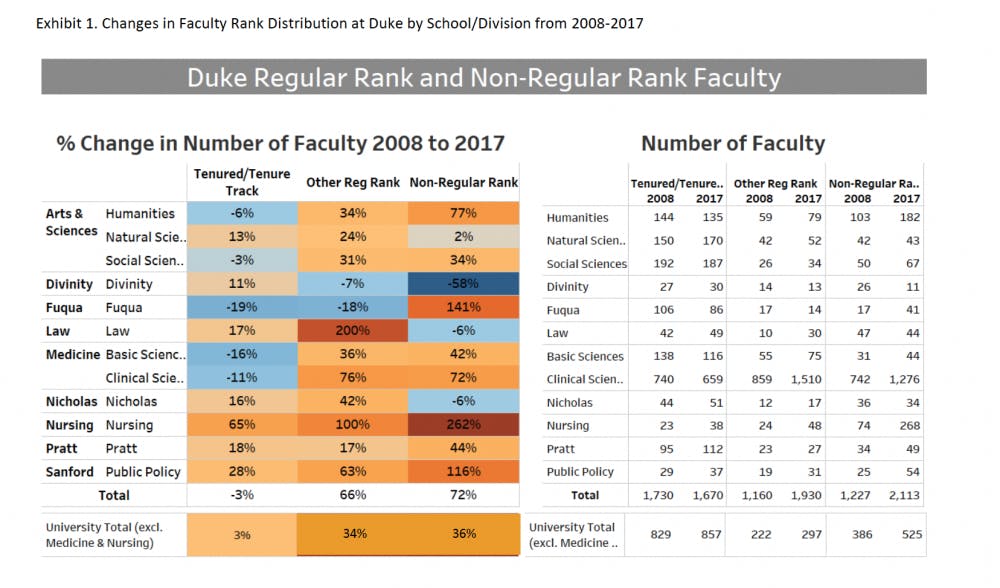

By the raw number of faculty at the University-wide level, there are nearly 900 more non-regular rank faculty members now in 2017 than in 2008—a jump from 1,227 to 2,113. The number of non-tenure track regular rank jumped by nearly 800, from 1,160 to 1,930. On the other hand, the number of tenure-track regular rank faculty declined by 60, from 1,730 to 1,670.

Duke did not have reliable data for the non-regular rank faculty at Duke before 2008, according to the report.

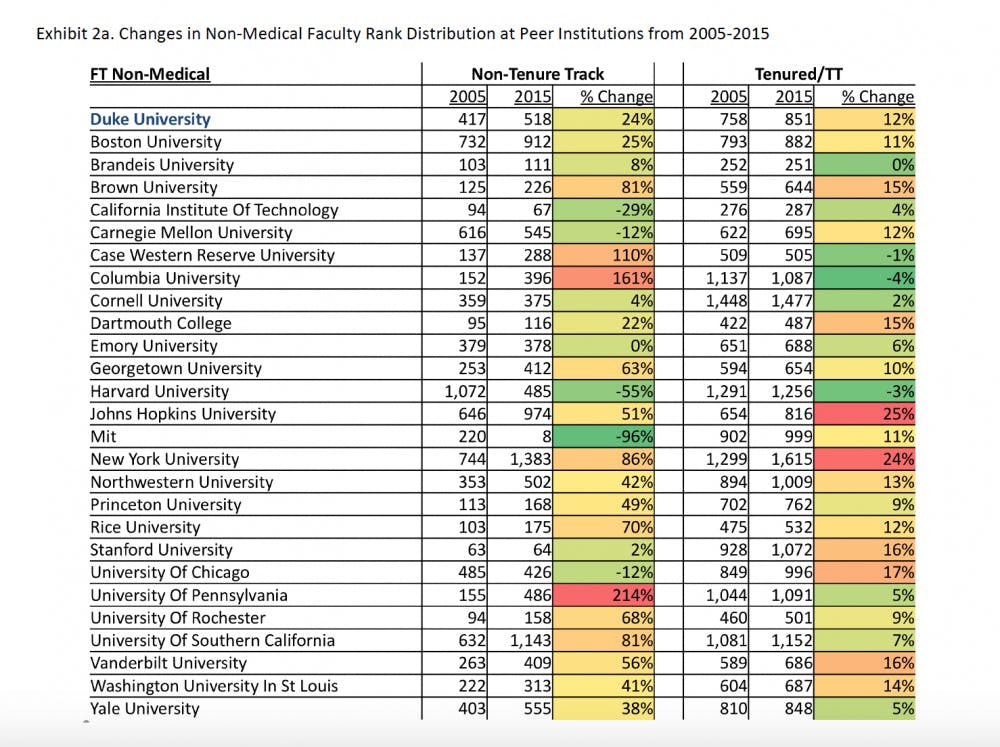

This trend towards non-tenure track faculty is not at all unique to Duke. The report included information about faculty rank distribution changes at peer schools in the Association of American Universities, although most schools do not have the non-tenure track regular rank category and instead lump them in with the non-tenure track category.

Some schools have had even more dramatic changes than Duke. Columbia University has had a 161 percent increase in non-tenure track faculty, and a four percent decrease in the tenure-track faculty. The University of Pennsylvania increased its non-tenure track faculty from 155 to 486, a 214 percent increase.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

On the other hand, Harvard’s percentage of non-tenure track faculty dropped by 55 percent and the Massachusetts Institute of technology dropped its number of non-tenure track faculty by 96 percent—from 220 to eight.

What caused the shift?

Fitzsimons' committee spent a year meeting with all of the deans and leadership teams at each school, as well as leadership from the Duke Faculty Union. The resulting report highlighted the numerical change, but also named three key factors the committee found to be behind the change.

“The committee saw that that ratio seemed to have shifted pretty dramatically,” Fitzsimons said.

An important one was the 2008 global financial recession, which forced schools to look more closely at their budgets. Fitzsimons explained that the committee thought this was one of the most important factors that explained similar changes at other schools.

The cost per class is cheaper for non-tenure track regular rank or non-regular rank to teach the class than for non-regular rank faculty to teach them. Even if non-tenure track regular rank faculty are paid the same as regular rank faculty, they typically are expected to spend less time on research and therefore cost less per class because they can teach more classes.

Another key shift highlighted in the report was the growth of master’s programs. Those are largely staffed by non-tenure track faculty, whether they are non-regular rank or non-tenure track regular rank faculty, Fitzsimons said.

“I think there is no question that most of the schools are trying to balance their budgets and bring in more revenue,” Fitzsimons said. “Unambiguously, a source of new revenue are these master’s programs. So I don’t see that pressure letting up.”

Another factor is the medical center's growth.

If you remove schools with large populations of clinical faculty—specifically the School of Medicine and School of Nursing—the numbers are slightly less dramatic. Under these constraints, tenure track faculty population grew by three percent, while the non-tenure track regular rank faculty grew by 34 percent and the non-regular rank faculty grew by 36 percent.

A key concern is that it was not a strategically planned shift.

“That’s a big shift,” Fitzsimons said. “If you go back, it’s not as if somebody said ‘Hey, here’s the plan.’”

What this means for Duke

Christopher Shreve, instructor in biology and president of the Duke Faculty Union, said that the findings of the report do not surprise him.

“It doesn’t surprise me, based on my experience here and based on well-established trends across higher education,” said Shreve, who has taught at Duke since 2003. “It is not surprising that Duke is not immune to market forces being what they are, and to the potential crises in higher education.”

The sharp uptick in non-regular rank faculty was one of the driving factors in forming the faculty union, Shreve explained.

Because adjunct positions were originally envisioned as temporary roles, they needed to be adjusted as faculty began to hold them for longer terms. The collective bargaining agreement that the faculty union signed with the University last year helped with that, Shreve explained, letting the adjunct faculty take on longer contracts and introducing minimal levels of pay.

“The committee unanimously felt that one couldn’t earn a living wage on the amount of money paid to adjunct faculty,” Fitzsimons said.

Another key impact of the change that the report highlighted was the potential effect on the University’s research output and interaction between researchers as professors and students.

At Thursday’s Academic Council meeting, the faculty governance body discussed the report.

Provost Sally Kornbluth suggested that the shift may be augmented by increasing segmentation within some schools, and Sara Beale, Charles L. B. Lowndes professor of law, said that the change in the law school’s faculty has largely come from their creation and growth of law clinics.

‘What the faculty is going to look like in the future’

If the University decided it wanted to dramatically undo the shift, it would not be simple. Cost pressures remain an issue, and there are now institutional constraints tied in with the collective bargaining agreement to mitigate that, Fitzsimons said at the council meeting.

Shreve said that maybe it’s not a good or bad change—but just a change.

Going forward, the committee recommended a few ways to be more transparent about the shift.

Academic Council should receive a report every year on the makeup of the faculty, the committee said, and diversity should be a goal at all levels of hiring.

"It is not acceptable to have dramatic differences in the approach to faculty diversity across both groups," the report stated.

All tenure-track faculty should be committed to teaching alongside their other roles and the use of titles should be more standardized across the schools. The committee suggested that each dean should submit a plan every five years regarding the composition of their faculty, and that any new master’s programs that are proposed should be transparent about how they plan to staff it.

Additionally, the committee said, there should be transparency in curricular discussions about how changes may affect the makeup of the faculty.

“We’re really talking about what the faculty is going to look like in the future,” Fitzsimons said.

Bre is a senior political science major from South Carolina, and she is the current video editor, special projects editor and recruitment chair for The Chronicle. She is also an associate photography editor and an investigations editor. Previously, she was the editor-in-chief and local and national news department head.

Twitter: @brebradham

Email: breanna.bradham@duke.edu