Content warning: this column contains references to sexual assault.

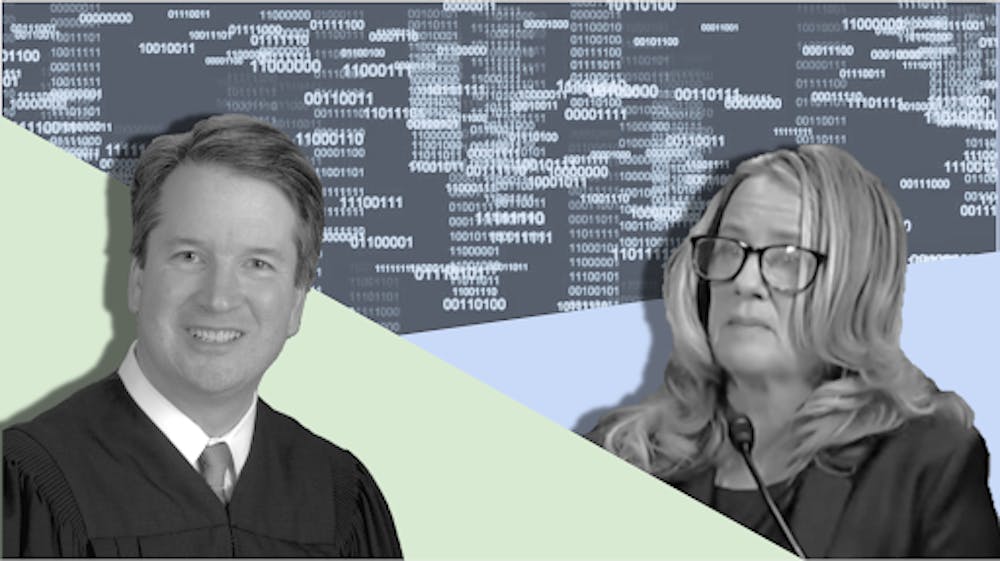

With no clues yet as to the findings of the FBI’s probe into Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations against Judge Brett Kavanaugh and what its subsequent outcomes may be, we only have last Thursday’s testimony to look to for answers. Unfortunately, however, the spectacle that unfolded sparked a particularly viral outbreak of political punditry that has functioned to obscure our memory of the hearing. The conflicting theories, revisionist histories and political prophecies that have since emerged have clouded our collective vision. Luckily, however, we have transcripts, and the data that they contain brings a more clear story into focus. What follows here is a limited analysis into those transcripts; an analysis that I have the privilege to do since I have not had personal experience with their subject matter.

By performing a standard type of data analysis used on human language data, sentiment analysis, two unambiguous pictures emerge from Thursday’s hearing. One testimony encodes great intensity of emotion with wide and predictable fluxuations in anger. While the other is characterized by consistently lower and more constrained emotional magnitude. The first speaker was auditioning for a lifetime on the Supreme Court and the second was recounting her assault on national television.

The set of data science techniques used to generate the data above belong to the family of natural language processing (NLP), which is used to ingest and interpret large sets of human text data. By processing the hearing transcripts and performing sentiment analysis, each sentence can be scored based on how strongly it encodes each emotion. Here I focus on anger as scored by IBM’s tone analyzer. The science of this sentiment analysis uses a combination of known linguistic correlations (e.g. curse words indicate anger) and machine learned features from millions of tone-tagged sentences, to accurately predict the emotion attached to human language. In all, the data plotted above provide us objective insight into the emotion that was being conveyed in each sentence by each speaker.

The characterization that emerges from the data — Kavanaugh combative and Ford composed — is one that matches widely covered intuitions. However, the visual distillation of these trends provides us a lens through which we can scrutinize these testimonies and our intuitions about them more rigorously.

The graph of Kavanaugh’s testimony has two notable features: the magnitude of anger and its wide fluctuation. The intensity of the anger encoded in his language began explosively in his opening statement and remained comparatively high throughout his entire testimony. More interestingly, the sharp rises in the anger observed in his language correlate highly with who he is speaking to. More precisely, peaks occur when responding to Democratic Senators on the Judiciary Committee like Sen. Durbin (D-IL) and Sen. Blumenthal (D-CT) and troughs occur when he speaks with Republican senators. This partisan correlation of his anger highlights the explicit and unprecedentedly partisan tone he was willing to submit to, as compared to previous SCOTUS nominees.

The graph for Ford draws a stark contrast. After sharing a similarly emotional opening testimony, the degree of anger encoded in her language dropped precipitously and remained low throughout the duration of questioning. She shows no partisan preference for the Democratic senators or prosecutor Rachel Mitchell. Ford also showed almost no significant variance in her emotional valence despite recounting immense trauma and personal details. And, despite her temperament, Ford apologized more (10 to 5) compared to Kavanaugh and felt the need to lighten the mood (as denoted by laughter 9 to 7) more frequently.

This data tells a familiar story, one that plays out from the theater of the the Capitol to the lecture halls at Duke. A woman keeping her cool, restraining her anger, and seeking to create comfort for others, (sometimes even for 11 hours) to avoid being viewed as overly emotional or not credible. A man, more inclined to public rage and sparse in apology, protected by the fraternal bonds of bureaucratic power.

Further still, this data can and should color our understanding of Kavanaugh as a jurist. It answers our questions about how he responds to pressure and party. It displays the limits of his temperament independent of rationalization or justification. The American Bar Association qualifies judicial temperament as “compassion, decisiveness, open-mindedness, courtesy, patience, freedom from bias, and commitment to equal justice under the law.” Judge Kavanaugh’s answer to each of the aspirational qualities can be found the sharp peaks of his testimony.

Where the transcript data becomes less useful is in deciphering the various possible motivations and rationalizations for the behavior quantified here. The transcript data cannot help us tease out if his rage was fueled by a sense of entitlement and fear or if it was driven by a belief that the allegation was false. It cannot tell us if the timing of her allegations and herculean restraint was a result of a political agenda or a genuine fear of retribution. Luckily though, I have one final piece of data to guide us at this crossroads: false sexual assault allegations make up only three percent to eight percent of all reported cases. This fact combined with the data of each testimony, serve to compose this week’s bit of useful stats advice: Believe her.

Luke Farrell is a Trinity senior. His column, By the Numbers, runs on alternate Thursdays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.