A bacterium known to cause stomach cancer may also lead to an increased risk of colorectal cancer, especially among people of color, a study by researchers at the Duke Cancer Institute found.

“People of color are more likely to be diagnosed and die of colorectal cancer," said Meira Epplein, associate professor in population health sciences and leading research of the study. "If H. pylori was associated with colorectal cancer, it could explain some of this racial disparity and provide a potential intervention point to screen high-risk people and eradicate their H. pylori.”

This potential for a medical breakthrough motivated researchers to further explore the link between H. pylori and colorectal cancers.

Epplein said their study was inspired by a 2013 study at Vanderbilt University, according to which individuals with high levels of antibodies to specific H. pylori proteins—indicating an occurrence of past infection—are at a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer. The study showed presence of protein-specific antibodies correlates to an increase in odds of colorectal cancer.

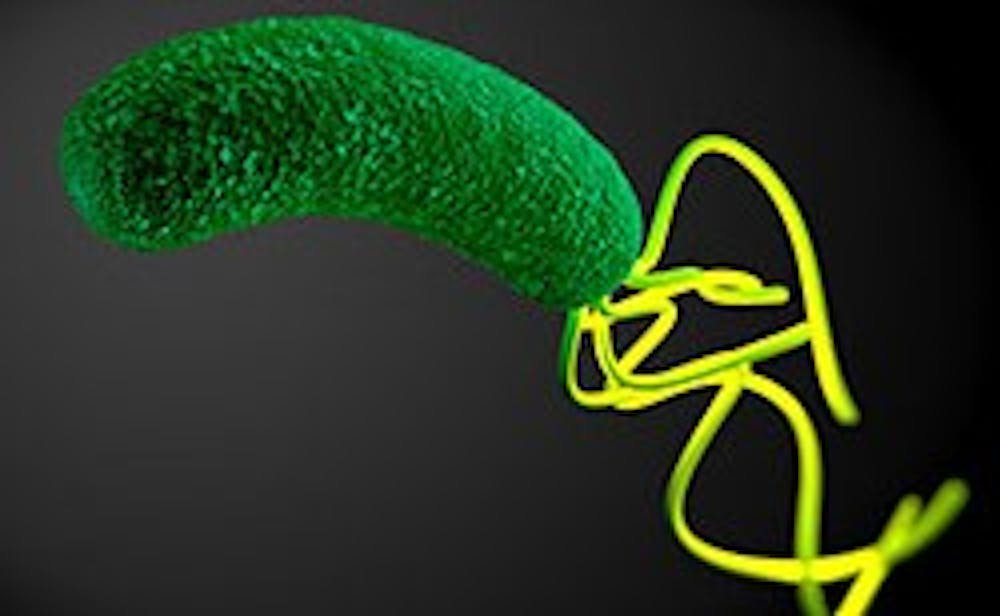

More than half of the world’s population is infected with the bacterium H. pylori, a common human carcinogen that has genetically evolved to live in the human stomach. The bacterium induces gastric cancer and stomach ulcers.

After obtaining a grant for the study in 2014, researchers at Duke amassed a consortium of colorectal cancer cases with matched controls.

With subjects from the community health clinics in the United States, they collected samples from racially and ethnically diverse subjects and examined the antibody levels before any cancer development. Of more than 8000 study participants, half went on to develop colorectal cancer.

These participants were then matched with control subjects of the same age, race, sex and other features, Epplein said.

To determine whether presence of antibodies increased the odds of developing colorectal cancer, researchers compared the antibody frequency between the cancer and non-cancer subjects, she added. They observed a similar occurrence of past infection in both groups.

However, they noticed that ethnicity made a difference: a much higher proportion of black and Latino subjects harbored antibodies to H. pylori. This finding was consistent across both the cancer and non-cancer groups, Epplein added.

Antibodies to specific H. pylori proteins were also found to be present most often among different ethnic groups. Most significantly, high levels of antibodies to one H. pylori protein—the VacA protein—was strongly associated with colorectal cancer incidence among African Americans and Asian Americans.

The knowledge that the association between H. pylori and colorectal cancer is pronounced among people of color can significantly impact treatment options, courses of action, and public health disparities concerning cancers.

If there is a causal linkage between the presence of H. pylori and colorectal cancer development, medical professionals could identify people at high-risk of developing colorectal cancer based on their H. pylori status and reduce cancer incidence by treating them, Epplein noted.

"Eradicating H. pylori is both non-invasive and cost-effective, only requiring 2 weeks of antibiotics alongside a proton-pump inhibitor," she added.

If researchers can prove that H. pylori does not lead to a higher risk of colorectal cancer development, the study is still valuable, according to Epplein.

"If we find that it is not causal, it is still a biomarker—a sign of increased risk," she said.

Medical professionals could still use the level of antibodies to specific H. pylori proteins to screen people for their probability of developing colorectal cancer.

"For example, if people have high levels of VacA antibodies, they could be getting colonoscopies more frequently," she said. "And for colorectal cancer prevention, we already have the great tool of colonoscopy, which reduces risk and catches cancer early.”

Before establishing H. pylori as a definitive cause of colorectal cancer, researchers are still trying to understand the association that the study discovered.

Epplein speculated that high antibody levels to common bacteria may indicate a high pro-inflammatory environment, which may make one more likely to develop inflammation-related cancer.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

H. pylori is beneficial for humans when they are young by training their immune system to not over-respond to harmless antigens like dirt, mold, and dust, Epplein said. But it will evolve over time as people age.

"Now that we are living longer, the benefit-harm ratio changes at a certain age," she said. "In older people, H. pylori has replicated so many times that it creates more of an opportunity for a mutation."

This mutation could be a potential cause of different types of cancer, she added.