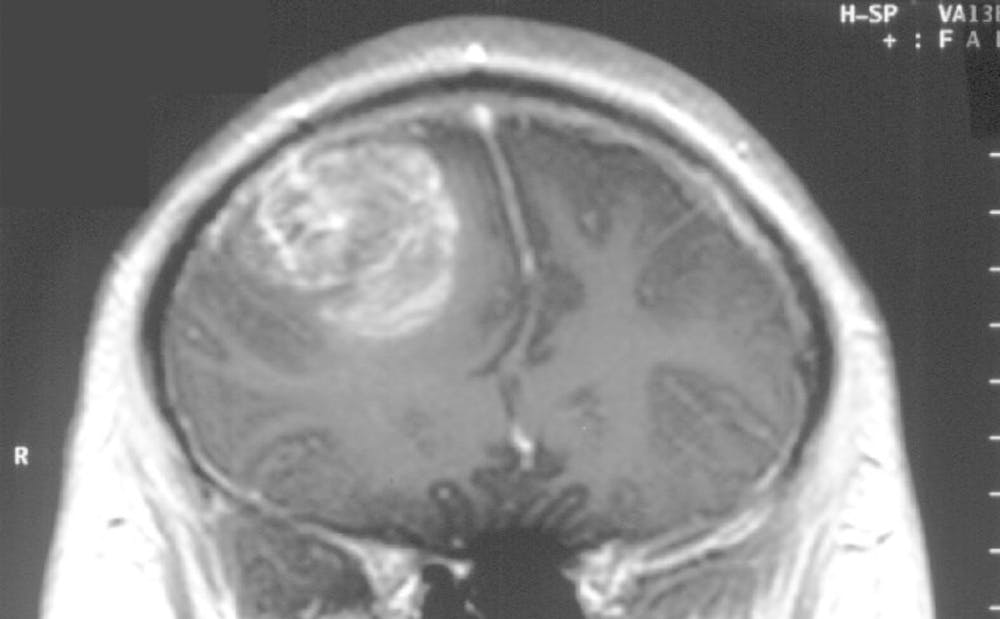

Researchers at Duke have recently discovered a missing link that could be a breakthrough in treating glioblastoma—an aggressive form of brain cancer that doesn't respond to usual treatment.

Part of the reason glioblastoma is so deadly is that patients with the disease have extremely low counts of T-cells—white blood cells that fight cancer—that can be as low as 200 compared to a healthy individual's 7,000. T-cells are a major part of the immune system, so glioblastoma patients face an incredible challenge: fighting cancer with the immune system of a person with AIDS.

“It’s a beautiful balance that our bodies must achieve,” said Pakawat Chongsathidkiet, a postdoctoral student on the research team. “In autoimmune disease, your immune system almost works too well—it starts attacking your own body. In cancer, your immune system doesn’t work well enough.”

After years of intensive research, the researchers in the lab of Peter Fecci, assistant professor of neurosurgery, has finally discovered why—trapped T-cells.

Initially, the lab believed that something was preventing T-cells from being produced—so researchers looked at the bone marrow, the site of T-cell production, expecting to find low T-cell counts. Shockingly, they found hordes of trapped T-cells, blocked out from exiting the bone marrow and reaching the body.

When they analyzed the trapped T-cells, the lab found that they lacked the protein—S1P1—responsible for enabling T-cells to enter the blood, so the cells remained trapped and useless.

The lab is currently working with Robert Lefkowitz, James B. Duke professor of medicine, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2012 for discovering this protein class.

Together, Lefkowitz and researchers at the Fecci Lab hope to find a way to restore the receptors to the surface of trapped T-cells, freeing them to the bloodstream so they can fight cancer.

“We believe there is some interaction between the tumor and the surrounding brain environment that’s causing the T-cells to be trapped,” Chongsathidkiet said. “Somehow, the cancer usurps the brain’s mechanism for regulating T-cells.”

The significance of this research is profound, even though the incidence of glioblastoma is very low. There are no more than five or six cases of the cancer per 100,000 people, with median survival only 15 months following diagnosis.

Patients suffer from seizures, memory loss and personality change amongst other torments.

“People might think that for the public health system as a whole, this might not be that important,” said Chongsathidkiet. “But you can’t evaluate the cost of losing even a single life. Even if it’s a small number of people, we can’t abandon them.”

The presence of glioblastoma is tragic and often very visible to the public eye. Beau Biden, Sen. Ted Kennedy and Sen. John McCain were all victims of the cancer.

The research may prove contribute to future treatment of the cancer and of brain cancer more broadly.

“Whatever we learn from this study can be applied to brain metastases as well,” said Chongsathidkiet. “Metastases is when cancer spreads from the breast and lung to the brain. Brain metastasis is far more common than glioblastoma itself. Ironically, as cancer treatment gets better, we will see more patients surviving long enough to get brain metastases.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.