Acute lymphoblastic leukemia can wreak havoc when it spreads to the brain—but until recent Duke research, no one had shown how ALL manages to do so.

The research team discovered that ALL cancer cells have a special receptor allowing them to bind a protein called laminin on blood vessels that lead directly to the central nervous system. This allows the cancer cells to infiltrate the blood vessels and head straight for the brain.

“The ALL cells have a high propensity to go into the central nervous system," said Dorothy Sipkins, associate professor of medicine and senior author of the paper. "They want to be there for some reason and what we were trying to understand is how."

Sipkins likened the process to a firehouse, where the top floor of the firehouse is the bone marrow and the bottom floor is the central nervous system. The fireman’s pole is a blood vessel on which the ALL cell easily and directly slides down.

In the United States alone, there have been about 5,960 cases of ALL and approximately 1,470 resulting deaths in 2018, according to the American Cancer Society website.

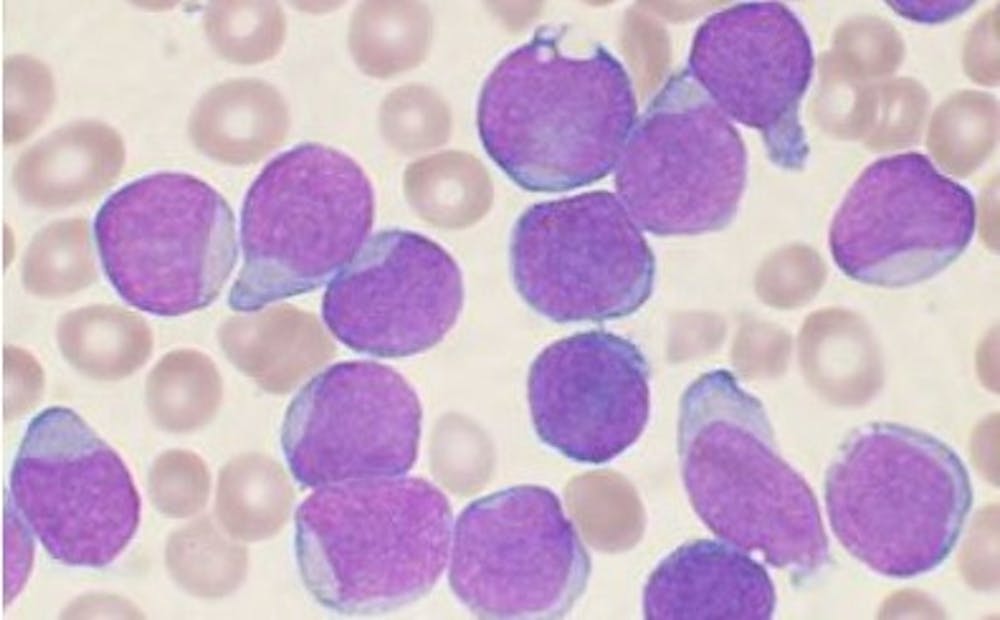

ALL is a deadly type of cancer that occurs when white blood cells in the body begin to grow uncontrollably and rapidly. For over half of patients with ALL, the cancer affects the brain by invading the central nervous system and makes recovery prospects much lower, Sipkins mentioned.

For decades, no one was able to identify how cancer cells enter the central nervous system.

Sipkins and her lab spent years of work trying to understand this mechanism. This deadly invasion of the nervous system was always thought to be caused by the cancer cells crossing the blood brain barrier, which acts to protect the brain from harmful substances.

“We tried by many means to identify the molecular mechanisms that could mediate that process," she said. "Every time we looked for that, we failed to find any evidence of the cells entering the central nervous system via that type of route."

After years of work, Sipkins’ lab had to re-evaluate and take a hard turn.

The discovery finally came when the lab was testing a drug in collaboration with a drug company. After administering the medication to mice that had ALL, Sipkins noticed that the only reason the mice were surviving longer was because they were not developing a central nervous system disease. How exactly the disease did not develop in the central nervous system still remained a mystery.

Sipkins noticed that the drug was not effective in completely eliminating the disease in the bone marrow—where the disease originates—but also knew that it could not penetrate the central nervous system to fight disease there. From these observations, her team was able to deduce that the drug was preventing the cancer cells from entering the central nervous system altogether.

“We thought, 'Wow, we finally have a tool to try and untangle this mystery,'” Sipkins said.

Despite the headway, the main issue still remained unsolved.

“The hardest part was finding how these cells actually get in from the bone marrow to the central nervous system,” said Trevor Price, a postdoctoral scholar in the Sipkins Lab and contributing author of the paper.

Currently, patients with ALL must go through aggressive treatments with great toxicity, but Sipkins said this new discovery could greatly minimize that. She admitted, however, that there is still a long road ahead and that she can’t overstate things.

Nevertheless, this paper is an apparent step forward in a long process.

“The ultimate goal is to develop a therapeutic treatment that could specifically target this mechanism that would prevent these cells from migrating from bone marrow to central nervous system,” Sipkins said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.