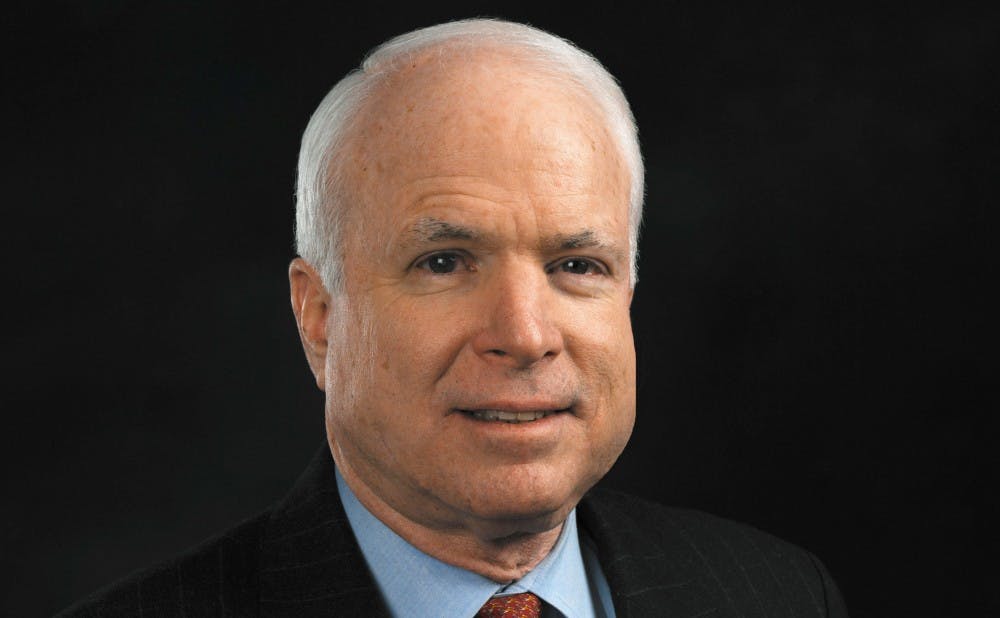

Americans came together last week to remember former Sen. John McCain. How they remembered him, however, varied.

On Twitter feeds and in opinion sections across the country, Americans discussed the prominent politician’s legacy. At Duke, two professors parsed the Vietnam veteran’s memory in a written back-and-forth.

Valerie Cooper, associate professor of religion and society and black church studies, penned an opinion piece in the Durham Herald-Sun Aug. 27 that injected discussion of McCain’s more controversial stances into the narrative of his legacy.

“In the next few days, expect many to laud John McCain’s military and political heroism while spending less time frankly discussing his weaknesses,” she wrote to open the piece.

On Sept. 3, Charles Dunlap, professor of the practice of law and retired major general, fired back. In a post on Lawfire—the blog of Duke Law School’s center for law, ethics and national security—Dunlap defended McCain’s “lifetime of service.”

“Much of her essay is offensive not just to the memory of Senator McCain and the sensibilities of those that grieve his death, but also to veterans and those who care about them,” Dunlap wrote in response to Cooper.

The two have not met each other, Cooper wrote in an email.

“I especially hope that the conversation will maintain a civil tone, despite what might be strongly held opinions,” Cooper wrote to The Chronicle. “It is the mark of a great university that many voices are heard and differing opinions are freely expressed.”

In her opinion piece, Cooper weaved the parts of McCain’s life that are viewed positively with the less-discussed negative parts, such as a divorce in the 1980s. She also took a critical lens to his support for military interventionism, calling him a “military careerist.”

“Might he have seen the wars differently had he seen them through the eyes of a child of Iraq or Afghanistan rather than through the eyes of a U.S. military careerist?” she asked.

The Divinity School professor framed the politician’s passing in the immediate and mortal terms with which people view the passing of famous individuals.

The initial response is bereavement and mercy for the person’s family and loved ones, Cooper wrote, but as McCain is embedded in the national memory, his legacy will become a more nuanced topic.

“We are not wrong to mourn the passing of an era or admit pain at this death,” Cooper wrote in the opinion piece. “Nevertheless, while we, as a nation, grieve John McCain’s death, we must also begin to reckon with his legacy. That reckoning is a longer, messier process that requires both time and distance from the man himself.”

In his blog post responding to Cooper’s op-ed, Dunlap called out Cooper for her use of the term “military careerist,” calling it a “slur of the first order.” He noted McCain’s choice to remain a prisoner of war in Vietnam until all the POWs were offered freedom, despite being offered early release.

“To me, the op-ed conjures up stereotypes about those who served, labels that date back to the Vietnam War,” Dunlap wrote in the blog.

The retired military officer stated that the majority of Americans have more confidence in the military than other American institutions.

He pushed back on Cooper’s questioning of how McCain’s perspective would have been different if he saw it through the lens of a child in a war-torn country.

“If the 'child of Iraq' was a 12 year-old Yazidi girl in 2015, she might have said, please save me from rape and sexual slavery that I’m seeing all around me, and that I’m a victim of as well,” Dunlap wrote.

At the conclusion of the defense, Dunlap noted that McCain was imperfect, but that imperfect people can still do great things.

“McCain wanted to be remembered simply as someone who served his country, and that he clearly did. Similarly, General MacArthur wanted to be remembered as someone who 'tried to do his duty as God gave him the light to see that duty,'” Dunlap wrote in the blog post. “Isn’t that what we all should strive to do?”

Dunlap wrote in an email that he thinks it’s important, in a time of political divisiveness, to seek understanding with one another on an individual basis and in groups people are associated with.

Cooper noted they may agree on more than is apparent in their contrasting writings. One point of agreement Cooper said she did not explore in the op-ed was about McCain’s later regret regarding the United States’ participation in Iraq and Afghanistan.

"We agree on these points: mistakes were made and John McCain acknowledged them as such,” Cooper wrote to The Chronicle.

Cooper noted that she is grateful for the free press “to allow people of good will and divergent opinions to be able to engage in this debate,” and she noted appreciation for Dunlap’s recommendation to readers to decide McCain’s legacy for themselves.

“My essay was an invitation to begin the process of reckoning with John McCain’s legacy,” she wrote. “I appreciate Maj. General Dunlap’s contribution to that reckoning.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Bre is a senior political science major from South Carolina, and she is the current video editor, special projects editor and recruitment chair for The Chronicle. She is also an associate photography editor and an investigations editor. Previously, she was the editor-in-chief and local and national news department head.

Twitter: @brebradham

Email: breanna.bradham@duke.edu