Fifty years ago, during one of the most turbulent times in American history, Ernie Jackson and Clarence “C.G.” Newsome enrolled at Duke in the fall of 1968 with little fanfare.

When the two football players arrived as Duke’s first African-American scholarship athletes, The Chronicle made no mention of the historic milestone, but the duo set about leaving a lasting imprint on the school. Their success paved the way for hundreds that have followed them in the last half-century.

Jackson became one the Blue Devils’ all-time greats on the field, getting enshrined into the Duke Athletics Hall of Fame in 1986. Newsome struggled with injuries during his playing career, but stayed at Duke to earn master’s and doctorate degrees from the divinity school and served on the University's Board of Trustees from 2002-18.

“I ended being an All-American, C.G. ended up being a big Academic All-American,” Jackson said. “From a test-tube like situation, we both turned out pretty well.”

'An impossible dream'

Both Jackson and Newsome were prepared to be pioneers at Duke after finishing high school at predominantly white schools. The “freedom of choice” policy prevalent in the late 1960s in the South gave children the option to transfer to the formerly all-white schools in their districts, and Jackson and Newsome chose to do so for their junior and senior years.

Jackson grew up in Hopkins, S.C., in the shadow of the University of South Carolina, which did not recruit any African-American football players until after he arrived at Duke. Jackson starred at Hopkins’ predominantly white Lower Richland High School, but was harassed due to his race wherever he played.

Jackson recalled reading about perceived racial mistreatment UCLA's men's basketball team endured when it lost at Duke in 1965 with three African-American players and felt determined to help change the culture in Durham.

“I couldn’t have experienced anything worse than what I experienced in South Carolina,” Jackson said. “I remember going into stadiums, and other than the janitors, I was probably the only black person in the entire stadium, and I was called the n-word.”

Duke caught Newsome’s eye after he watched its football team on TV when he was 13 years old growing up in Ahoskie, N.C., about 130 miles northeast of Duke. He first remembers watching the Blue Devils play in 1963, the same year the University’s first five African-American undergraduates enrolled, though he did not know about that at the time.

“While I fell in love with Duke and Duke football, I didn’t bother to say anything to anybody because it just seemed like an impossible dream,” Newsome said. “I just knew I felt it. I never denied it.”

Newsome was talented enough to start as a freshman at Robert L. Vann High School and played against a team in Williamston, N.C., coached by Herman Boone. Boone was later portrayed by Denzel Washington in the classic sports movie “Remember the Titans” for his 1971 season when he coached the integrated T.C. Williams High School team in Virginia to the state championship.

Newsome later transferred to the predominantly white Ahoskie High School, where he won state championships in football and basketball, and Duke assistant coach Harold McElhaney visited Ahoskie to recruit him in the spring of 1967.

“I was in band practice there at Ahoskie High School, and I got word that the coach, Coach Vaughn, wanted me to come to his office,” Newsome said. “To my great and wonderful surprise, a Duke recruiter had shown up at Ahoskie interested in me. It was really like a dream come true.”

When Duke head coach Tom Harp visited just before Christmas in 1967 during Newsome’s senior year, Newsome signed to become a defensive end for the Blue Devils.

'Always had to be alert'

Jackson and Newsome did not meet until they got to Duke for preseason camp in 1968, but they quickly became close in a tense racial climate. Newsome remembers the first time the team played on the road at Clemson.

“These cheerleaders were carrying a flag—they came out right ahead of the team. They went to the center of the field, and they unfolded the biggest Confederate flag I’d ever seen in my life,” Newsome said. “Clemson’s band struck up Dixie, and everybody in the stadium came to their feet, including the Duke fans. I looked at Ernie, Ernie looked at me, we looked around the stadium, we looked over in the direction of our locker room and we saw a black maintenance guy.

“I remember focusing on that person for just a minute and just feeling in a setting where we had to be alert. And we always had to be alert.”

At Duke, Newsome said the two steered clear of some fraternities that were “more likely to express racist attitudes” than others, and there was some distance between them and their white teammates.

“We basically would stand on each other’s porches to survive because there was really no other teammate. I mean, you knew other guys, but you didn’t know them that well,” Jackson said. “There was not really any existence as far as your relationship other than football.”

Newsome and Jackson could confide more in the African-American students on campus, many of whom participated in the Allen Building takeover of Feb. 13, 1969. About 75 students, organized by the Afro-American Society, sat in Duke’s main administrative building for 10 hours and presented 13 demands to help black students at Duke.

The students were met with tear gas from the police when they exited the building and were disciplined harshly by the school. Newsome and Jackson did not occupy the building, and Newsome said the student leaders of the protest urged them not to so they wouldn’t jeopardize their scholarships.

“That led to a lot of kids either leaving school or being kicked out of school,” Jackson said. “I think it was probably 15 to maybe 20 of us left after that situation.”

'I just raised my game'

With few peers on campus, Newsome felt the effects of racial prejudice at times in the classroom as well.

“I had a faculty person stop me on my way out of the classroom one day and say to me that blacks couldn’t write, looking me right in my face. I don’t know where that came from or why he said it at that moment. And then he said black boys especially can’t write. I was stunned,” Newsome said. “I got about my business to prove him wrong and just made it impossible for him to not recognize my ability. I got early drafts of my essays and all that kind of stuff together and I then had two or three people read it and edit it. I just raised my game.”

A couple of years later, Newsome was appointed the acting dean of black affairs in 1973 while he was in his master’s program at the Divinity School. One of his duties was to oversee Duke’s pre-college summer transitional program, and he said one day, that same professor walked into his office and asked for a job with the program.

“A lot of people tend to think that I said no. I said yes, but only after he and I talked, because I revisited that story that I just shared with you, and I shared with him how I felt that that was not reflective of the best pedagogy,” Newsome said. “After we talked extensively, I was persuaded that he got it.”

'Window dressing'

Both men were cheered and admired by the African-American fans at their games, whether they played at home or away. Newsome said every time he ran onto the field at Wallace Wade Stadium, he looked up at the unofficial black seating section in the top right corner across from what is now Blue Devil Tower. And when he suffered a knee injury that ended his sophomore season on the road at Virginia, he did the same.

“When the trainers helped me from the field, all the black students in Scott Stadium up at the University of Virginia stood up and gave me a standing ovation,” Newsome said. “That gives you some sense of the kind of unity among black students at all those predominantly white schools.”

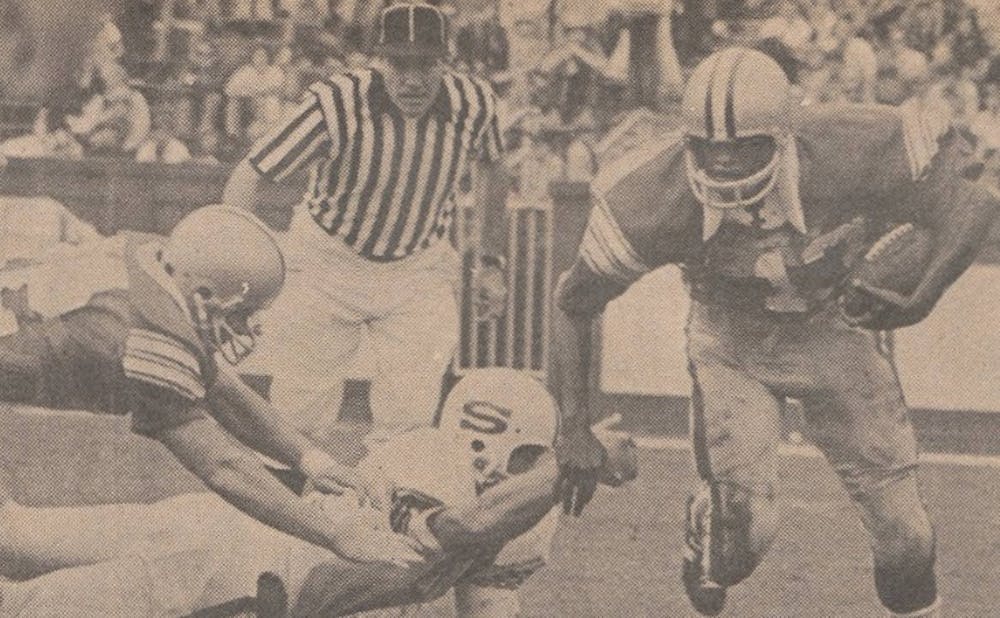

Newsome hurt his knee again during their senior year in 1971, but Jackson became recognized as the team’s biggest star playing both offense and defense as a cornerback and tailback. He scored two touchdowns in a victory against his hometown school South Carolina—one on a punt return and another on an interception return—and he ran another interception back for the only touchdown of a 9-3 win against Stanford.

The Blue Devils finished with a 6-5 record for their second straight winning season in Mike McGee’s first year as head coach after he took over for Harp, and Jackson became the first African-American ACC Player of the Year.

But Jackson struggled to remember his on-field heroics fondly, instead expressing some disappointment that he didn’t feel as appreciated as he deserved during his time at Duke.

“It just seemed to me that they were so interested in going that particular direction, it was almost like window dressing,” Jackson said. “Black people were just there to say, ‘Yeah, we have black people,’ but not really capitalize on it.”

Jackson went on to have an eight-year NFL career, mostly with the New Orleans Saints, before going into business and retiring to follow his daughter Jamea Jackson’s professional tennis career. He now lives near Memphis, Tenn.

'True blue'

On the other hand, Newsome remains closely connected to Duke. He became the first African-American to give the school’s student commencement address in 1972, and after staying to earn two more degrees, he became the dean of Howard University’s divinity school, the president of Shaw University, and most recently the president of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati.

While he served on Duke’s Board of Trustees, Newsome was part of the search committees to hire head football coach David Cutcliffe and Kevin White, vice president and director of athletics. Last year, the area outside the Yoh Football Center was named the C.G. Newsome Players Plaza thanks to an anonymous gift in his honor, and he was elected a trustee of the Duke Endowment in May.

“There isn’t anybody who loves Duke football more than I do,” Newsome said. “I’m one of those persons who you might say is truly true blue.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story said Jackson recalled that UCLA basketball great Lew Alcindor—now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar—endured harassment at Duke, but Alcindor was on the freshman team in 1965 and did not travel with the varsity team to Durham. He played Duke in Los Angeles in 1966. The Chronicle regrets the error.