At Duke there is no shortage of hard choices to make: what classes to take, which consulting jobs to apply for, who to fall in love with, or whether or not to wake up for your 8:30 lecture. But one choice, above all others, we struggle with the most often—what to eat at West Union. And while it is a tremendous privilege to have access to all of these dining options, it can certainly induce choice fatigue. With 13 restaurants of unreasonably high quality (and price) available, the daily choice of what to eat has led to a Sisyphean nightmare of countless laps around our glass dining purgatory.

This choice fatigue often leads us to default into predictable patterns and miss out on the bounty of options around us (we both know you’ve eaten Tandoor the past four days in a row). That’s why sometimes the best way to make a choice is to randomly choose. In fact, occasionally making random choices is the bedrock of achieving the highest possible utility over time, which in our context means having the best possible eating experience and exploration over the lifetime of your Duke career. But, while statistical randomness may be the key to your culinary nirvana, making truly random choices presents a problem: it’s impossible.

True randomness generation remains mathematically illusive, and to make matters worse, humans are remarkably bad at generating even seemingly random selections. For example, when asked to pick a random number between 1 and 100, most people will choose a number that is odd, often prime, and approximately 1/3 or 2/3 of the way between the lower and upper limits. This incapacity to act randomly has plagued professional poker players for centuries, since less predictable bluffing strategies are central to success at the highest levels. Our incapacity to generate anything resembling randomness is a well known phenomenon and certainly disqualifies us from making a truly random meal selection for lunch.

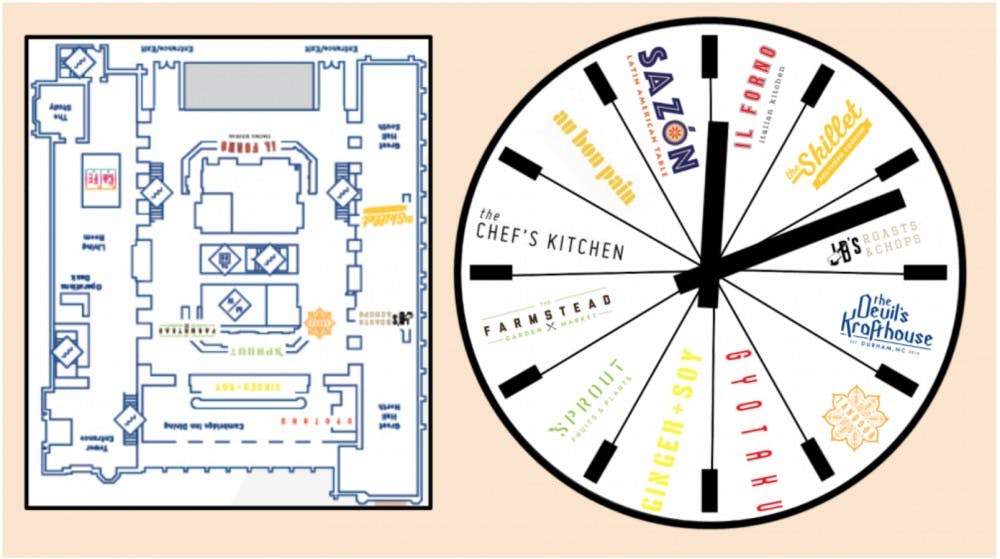

So, borrowing from the oldest probabilists we have (gamblers), I present to you the answer to your food choice woes: the succinctly named pseudorandom-west-union-food-choice-generator.

No, it is not an app: writing this column is enough unnecessary labor already. It’s a clock, the oldest and most widely used pseudo-random number generator we humans have yet to devise. Everything from the security of your Facebook data to your bank account relies on the randomness of a clock and now you have the power to use it to pick your next $13.00 meal at Duke.

The way this random choice generator works is simple: the instant you are trying to decide what to eat, look at your watch. At this moment in time, the second hand (the one counting seconds), will be pointing to a pseudo-random number. Since unconscious human perception of time at the scale of seconds is imprecise, and the last time you took note of your watch’s second hand was likely a very long time ago, the location of the second hand is a remarkably good pseudorandom number for our purposes.

Now, with your pseudorandom number and a mapping of each of the West Union’s twelve restaurants (excluding the Commons) onto the clock face, your choice is made. Wherever the second hand of your watch is pointing is where you’ll be eating (it’s only Tandoor 1 out of 12 times). For convenience, the mapping I’ve included here aligns roughly with the location of each restaurant when orienting your watch with the glass wall of the West Union.

The restaurant our pseudorandom-west-union-food-choice-generator chooses is drawn from a vastly “more random” distribution than any choice a human mind could conjure up, and it is guaranteed to help you expand your West Union palette. But, as with most advice from mathematics, it comes with a few caveats. First, this watch-mapping assumes that you desire equal probability randomness across options and that you currently don’t sufficiently explore the West Union’s dining choices enough. Second, it makes the savvy choice of excluding The Commons, because no one should pay twice as much for Pitchforks fries. Third, the choice generated is only “pseudo” random, meaning it is seemingly random to the observer and only meets some basic conditions of statistical randomness. And finally, it provides no assistance in choosing your actual meal once you arrive at your dining destination and doesn’t account for your dissidence either. As such, if you watch and wait for the second hand to slowly tick into the Tandoor quadrant, the methodology begins to break down.

So, try as you might to randomly choose what to eat or even have a friend randomly choose for you, chances are your random choice won’t be so random and you’ll end up at Tandoor again. Despite the tremendous upside exploration through random choices often presents, and our greatest efforts to achieve it, the pseudorandom-west-union-food-choice-generator is some of the best technology we have to work with. It is my hope that this tool may make the elusiveness of randomness a bit more manageable in your life and at the very least, help you not eat at Tandoor for the fifth day in a row.

Luke Farrell is a Trinity senior and requests that if you can’t decide what to eat just give him your food points instead of using the pseudo-random-west-union-food-choice-generator. His column, by the numbers, runs on alternate Thursdays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.