In the music video for Chris Brown’s “Freaky Friday,” the white rapper Lil Dicky wakes up in Chris Brown’s body. Now, just because he’s black, he can throw the “n-word” around as much as he wants. If you want, watch the clip here (fast forward to 2:19).

Lil-Dicky-in-Chris-Brown’s-body running down the street shouting “n****” is funny in the video, but it brings up a societal rule that I find unsustainable: if anyone who is not black says “n*****,” it’s racist, uncalled for and out of line. Meanwhile, black people and black rappers can throw it around all they want, because “it’s acknowledging our mutual struggle,” or “reclaiming” the power of the word. Earlier this year, Kendrick Lamar stopped a white fan who he had invited on stage to sing some of “m.A.A.d City” when she repeatedly said the n-word while rapping with him. She told him that she was used to singing it the way he wrote it.

What we, as a black community, say when we enforce this rule is that everyone can support black rappers and listen to their music, but when we all sing along, those who aren’t black have to stop singing every time the rapper says the word “n****” out of respect. It’s wishful thinking, but unfortunately, it’s not a rule we can expect everyone to follow all of the time.

As far as mainstream pop and hip hop music goes, both “Freaky Friday” and Drake’s “Nice for What” are some of the most popular songs this summer, and they both repeat the n-word throughout. This means that whenever we’re singing these songs with friends at a pregame, at a party or in the car—if we’re surrounded by people who are being conscious and respectful in the moment—everyone pauses for a second to let the word pass. Then, they keep singing.

But let’s say three friends, none of them black, are in the car on their way to get ice cream. The person sitting shotgun has DJ privileges. They’re driving fast down the road through town, singing the lyrics at the top of their lungs as lights and houses and shops fly past outside the window. And when Drake smoothly says “You really pipin’ up on these—” and drops the n-word, someone in the car lets it slip too. Now, what? Do we let it go as an innocent mistake? Does someone say “that’s not okay”? Is it okay as long as it was an honest mistake in the moment? Is it harmless because no one in the car is black?

As cases of non-black teens using the n-word become more and more common, the necessity of answers to questions like these becomes more urgent. I can’t be in every car full of teens or adults driving down the road when these songs play on the radio. I can’t expect every car to have one conscious person ready to explain why saying the “n-word” even as a joke does matter. I can’t expect everyone, black or non-black, to agree that saying the n-word in a song lyric is problematic. But the majority of the people I know want to be respectful of black people’s wishes, and it is to them that we owe more concrete answers. Here are mine:

I personally can’t stand hearing anyone say the n-word regardless of their race, have no desire to “reclaim” it, and think we should stop using it all together. I think that if a non-black person is singing and they know the n-word is coming, they should skip it. If it comes out by accident, telling them it’s not okay to say is enough—if they agree it is not their place to say it.

If they don’t agree, this is the problem we as a black community need to address: whether supporting rap music is worth putting up with non-black people who now feel comfortable using the n-word.

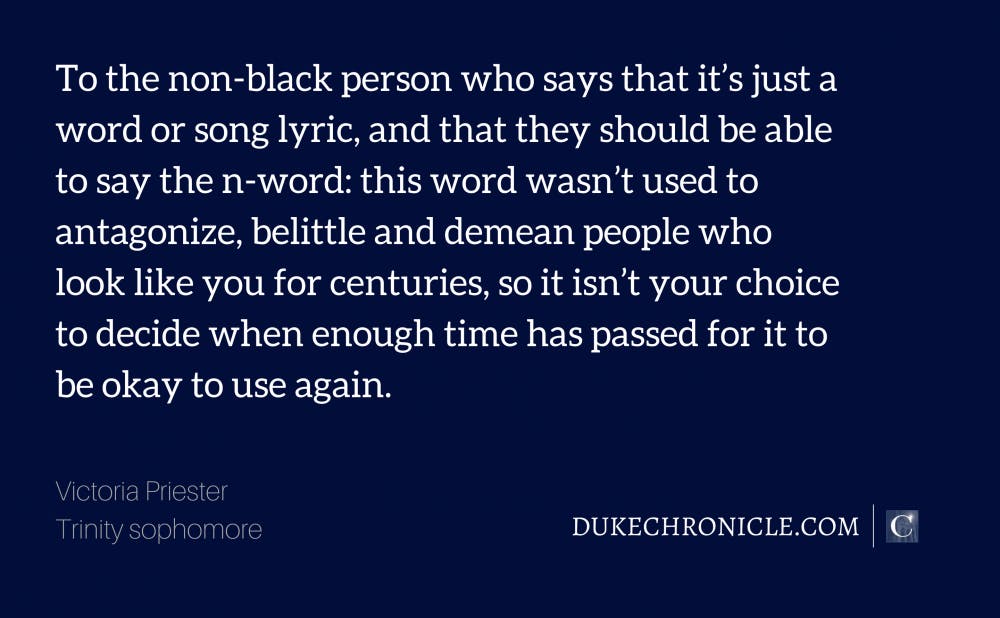

To the non-black person who says that it’s just a word or song lyric, and that they should be able to say the n-word: this word wasn’t used to antagonize, belittle and demean people who look like you for centuries, so it isn’t your choice to decide when enough time has passed for it to be okay to use again. To the black people who say the n-word is part of a redemptive counter-culture: we aren’t far enough removed from its malicious past to begin a redemptive revival. The word hasn’t died out yet, so we can’t bring it back. To assume such a transformation is possible would be the same as expecting a caterpillar to sprout wings and instantaneously become a butterfly without first retreating into its cocoon.

If the only place we saw or heard the n-word was in old Southern literature, professors could explain that this was a racial slur used to subjugate black people in the 20th century and that we don’t use it anymore. There are other racial slurs used in the past that most people wouldn’t even recognize if they heard them today, because as we as a society became more accepting of different races and religions, those words fell out of use. But we keep bringing the n-word back. If we left it in old movies and books and weren’t continually bombarded by it in popular music, I believe that the cases in which non-black people used it out of ignorance or out of malice would be fewer and far between. We are continually reminded of the persistence and potential power the “n-word” holds because we refuse to leave it in the past.

I’m not saying that I don’t like rap or hip hop music. I’ve long believed that rappers and hip hop artists are just as equally valuable as more “traditional” black intellectuals in their assessment of the social inequalities and profiling that have plagued black people and other minorities for centuries. N.W.A was blasting police for thinking “they have the authority to kill a minority” long before Ta-Nehisi Coates penned many of the same ideas in “Between the World and Me.” But as rap music and rap verses in pop songs become more and more popular, we hear the n-word in more and more of our favorite songs, and it becomes more normalized in our minds. Then, people who “aren’t supposed to say it” feel empowered to do just that: say it.

One could argue that perhaps, the common use of the n-word in popular music prompts more people to have conversations about who can say it. Or maybe after that one slip happened in the car on the way to get ice cream, that person puts more thought into being careful about using the n-word. But more often than not, it’s probably shaken off as a harmless accident. We resume singing, we keep driving without thinking too hard about the implications, and we don’t have a conversation. Maybe some people regard cases like this as harmless. But for others, no matter whether it was an accident or not, hearing the n-word or knowing that non-black people use it reminds them of past violence, racism, belittlement and the institutionalized white privilege that still exists today.

If we really want these cases to stop, one way is to call for entertainers to stop using the n-word in their songs. Kendrick Lamar’s music appeals to people of all races. Although he didn’t want his non-black fans to say the n-word, the fan he brought on stage was used to singing all of the lyrics the way Lamar wrote them, without pause. If rappers didn’t include “n****” in their lyrics, well-meaning fans wouldn’t be tempted to use it. Or, the fans who are tired of hearing non-black people say the n-word can also choose not to buy or download songs that have the n-word in the lyrics. If we don’t do anything to change the way the n-word is used in popular music, we’re going to keep hearing it.

A friend likened the issues surrounding the n-word to growing pains as a result of social integration—black music and rap are finally being accepted by listeners of mainstream pop music, but the consequence is hearing those who will never understand the plight of black Americans take the music that we use as consolation in our oppressed state and sing it as if it is the soundtrack to their own experience. It’s not. The n-word is a souvenir we have stubbornly held on to from a past that no one wants to return to. We’re clearly not at the point where we can be surrounded by music that uses the n-word and still respect the wishes of those it was previously used to disparage. Its power to hurt outweighs its potential as a means of social redemption for the black race. As the consumers of hip hop and rap music diversify beyond black people, we need to give the n-word a rest and leave it out of popular music.

Victoria Priester is a Trinity sophomore and columnist.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Victoria Priester is a Trinity first-year. Her column, "on the run from mediocrity," runs on alternate Fridays.