Larry Moneta, a vegan muffin and Young Dolph walk into a coffee shop. It sounds like the opening of a weird joke. But what follows, as most of us are well aware, is the unjust firing of two Joe Van Gogh employees.

After Dr. Moneta felt offended by the lyrics of Young Dolph’s “Get Paid,” he called one of his employees—the director of Duke Dining, a department that he oversees—and allegedly complained about the music. The Dining System later contacted Joe Van Gogh to convey this complaint, and somewhere along the line, the coffee shop fired the barista, Britni Brown, who played the music. Kevin Simmons, the other barista on the job, was also fired.

So the story goes, Dr. Moneta was offended by a rap song and took out his discomfort on the Black employee who cued the music, despite the fact that Brown said she shut the song off immediately upon his request. This following the University’s refusal to adopt a standardized hate and bias policy on the grounds of “free speech,” two clear incidents of targeted anti-Black hate, and a year of conversation about equity on Duke’s campus. What’s more, over the past month, Black Americans were targeted across the United States for BBQ-ing, being in Starbucks, entering an Airbnb, and napping.

It’s been a month since “Young Dolph-gate” went down. I think I’ve been avoiding writing anything for a couple of reasons: I was caught up in the frenzy of the end of the year, seeing my family, exhausted from the comotion of last semester, and quite frankly, I didn’t know what to say. How could I put into words the emotions that so many students felt? Who was I to comment on labor issues, and how could I do so purposefully? Most of all, what was even left for me to say?

But these were all excuses, meant to put off reflecting on my role in all this. It’s been a month. And after reflection and talking it through with much smarter peers, I have some thoughts.

The last few weeks of school were a wake-up call to many of us non-Black students.You can read about the details of the bigoted acts committed last April elsewhere, but they certainly represent offenses of hate and bias that should be addressed under “Demand 9.” Not only were they a reminder that blatant anti-Black racism persists across campus, but they were a frightening indication of the fact that anti-Black racism permeates other minority communities. It isn’t just white people who internalize white supremacy; rather, every person brought up into this culture holds it inside of themself and expresses it in myriad ways.

The hate incidents that occurred last May should compel each of us—yes, even those of us who belong to other minority groups—to critically examine our own anti-Blackness. More specifically, we should examine the way our anti-Blackness manifests itself on campus. Make no mistake, even our small, everyday interactions can be indicative of a larger racial hierarchy. Whose parties do we consider to be the norm? Which professors do we consider to be worthy of respect? What internalized assumptions do we have about Duke students in the Black community? If we care about the Duke community, we must feel obligated to address this hierarchy, and to protect our Black peers.

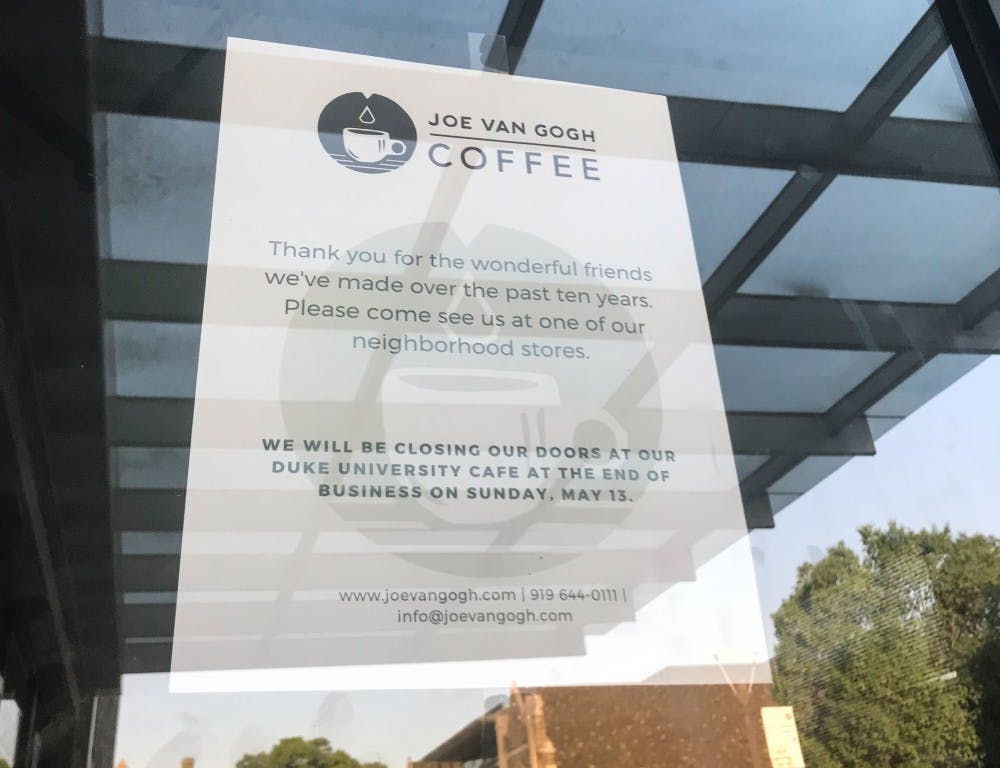

This obligation to supporting the Duke community does not stop with our Black peers. In fact, as undergraduate students, we exist in a self-sustaining ecosystem built around our interests. We exist in a world that requires the labor of tens of thousands of workers—undergraduates, graduate students, faculty, and non-academic employees—paid to create and maintain our utopia. Especially when it comes to non-academic and contracted workers,we often overlook the integral role that each employee plays within the Duke community. Young Dolph-gate is only the most recent case in Duke’s long history of treating its service employees as expendable. There may be many more employees whose stories were never picked up by the likes of IndyWeek, Complex, and Stephen Colbert. There may be many more employees whose lives and livelihoods have been changed at the drop of a hat, who have been dismissed unthinkingly and without review.

The gravest error we could commit is to assume that simply firing Dr. Moneta would solve these problems. In the end, this discussion is not about Dr. Moneta—it’s not even about free speech. Both topics distract from the real injustice at hand: a system that would so quickly and easily dismiss two real, valuable, beloved employees over a song. It’s the same system that offers no standardized consequence when a young woman’s door is defaced with the phrase “n***** lover.”

The injustice that we need to address lies in the fact that Duke still requires applicants to report their criminal-legal backgrounds on applications—effectively barring the formerly incarcerated from employment. It lies in the $500 per month childcare subsidy voucher that Duke offers—which is available for only one child, and is functional only at two campus facilities that cost nearly $1,500 per month. Despite protests and requests for affordable childcare beginning over three decades ago, one Ph.D. student told me that she often brings her infant to class while teaching. She can’t afford full-time childcare.

So if you’re like me, and you’ve been looking for an outlet to release the emotion that threatened to overwhelm throughout the last few weeks of the spring semester, you have plenty of options. First, we must resolve to recognize the value and dignity of every member of the Duke community. Then, we must seek to understand the ways our own choices reinforce anti-Black racism and labor exploitation. And finally, we must demand that the life of a contracted employee from Joe Van Gogh is just as valuable as the life of those with the most power: the Larry Monetas, the Tallman Trasks.

Let’s write the punchline to that joke about the vegan muffin and Young Dolph, and let’s make it a good one.

Leah Abrams is a Trinity junior. Her column, “cut the bull” runs on alternate Fridays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Leah Abrams is a Trinity senior and the Editor of the editorial section. Her column, "cut the bull," runs on alternate Fridays.