When I first toured Duke, everyone told me about the exciting city of Durham. My tour guide proudly stated that Bon Appetit Magazine had recently named Durham “America’s Foodiest Small Town.” As I began my first semester at Duke, I found this boasting about Durham’s food culture to be well-founded. Downtown Durham offers a wide variety of locally owned, popular and healthy options.

This upscale restaurant culture is linked to the up-and-coming nature of Downtown Durham. According to the 2017 Comprehensive Housing Market Analysis for Durham-Chapel Hill, average rent in Durham increased 5 percent from 2016 to 2017. This is over double the average rent increase for the state of North Carolina from 2016 to 2017, which was 2.3 percent.

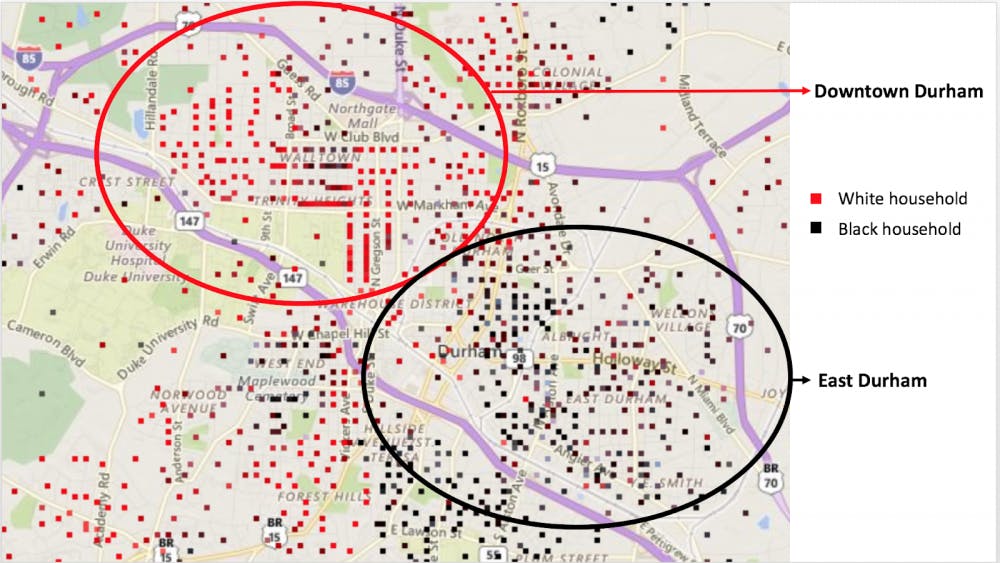

However, this increase in the cost of living is not equitably distributed through Durham County. The 2017 Market Analysis report also found that “rents are highest in the Northwest Durham/downtown market area, at $1,205 and the lowest in the East Durham Market area, at $968. The Northwest Durham/downtown...has seen a large amount of redevelopment in the past 10 years.” Duke’s placement in Downtown Durham and this redevelopment is not a coincidence, but rather a cause-and-effect relationship. Duke’s presence, as a prestigious university in the downtown area, directly influences the cost of living in Durham, increasing the racial and income disparity between Downtown and East Durham.

During my second semester at Duke, I began to volunteer as a court advocate for children of child neglect and abuse cases in Durham County. Many of my duties in this position included visiting my assigned children and their caretakers on a minimum monthly basis. All my children lived in East Durham, an area I had never been to before starting this position.

During my first drive from Downtown to East Durham, I was shocked by the disparity between the two areas. Downtown Durham is lined with kale bars, lush trees and newly paved sidewalks, while East Durham had McDonald’s, barely any forestry and cracked pavement. The racial disparity between the two areas is disturbingly distinct. The majority of my clients, as well as their families and friends, who live in East Durham are black and brown.

The map above is 2010 census data displaying black and white households in Durham County, with Downtown Durham and East Durham highlighted.

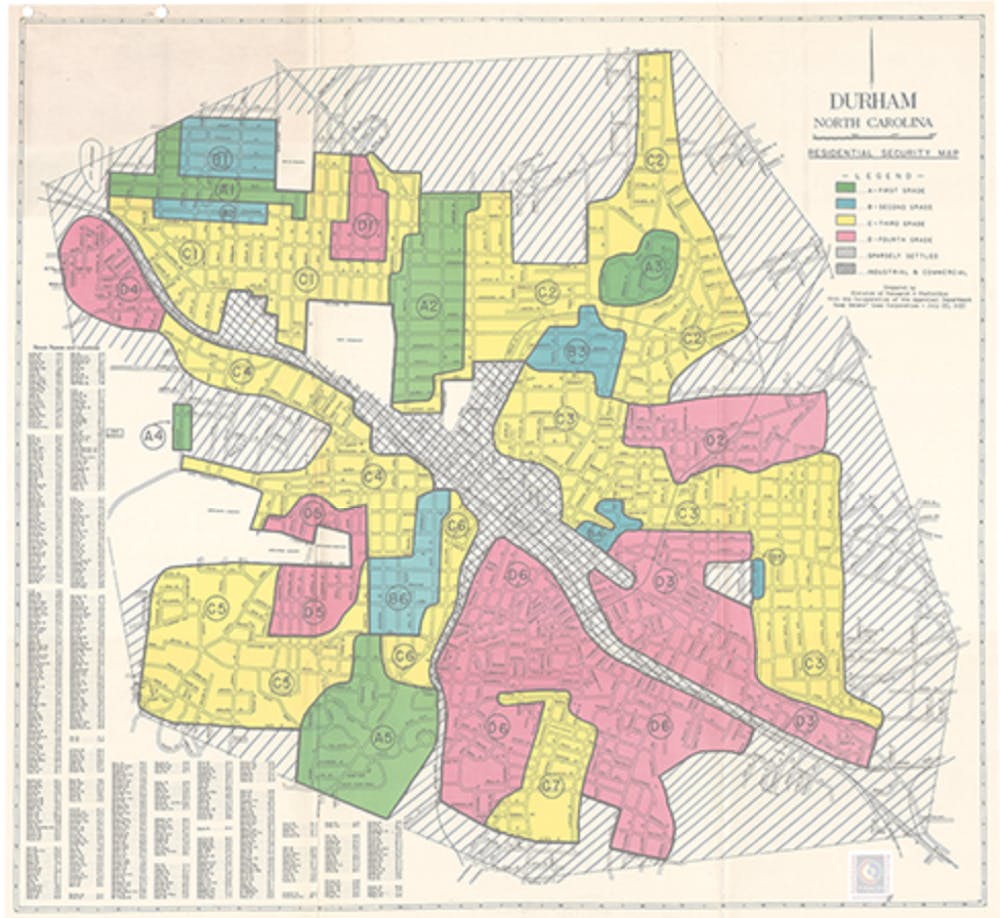

This disparity has deep historical significance. In 1937, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) created a map of Durham by categorizing areas as First Grade (blue), Second Grade (green), Third Grade (yellow), or Fourth Grade (red) based on the area’s “risk level.” This process, known as redlining, not only segregated the city based on race, but also had other lasting impacts. A study done by Duke's Nicholas School of the Environment showed that “East Durham has 40 percent less tree canopy coverage than traditionally higher-income neighborhoods like Trinity Park, a direct result of redlining.” The report concluded that this is linked to overall quality of life in the two areas, through air quality and heating/cooling benefits.

In 1949, Durham began urban renewal efforts; due to the construction of the Durham Freeway, this included the demolition of “substandard” housing. The families displaced by this urban renewal were largely located in East Duke, known as the Hayti area, and were disproportionately minorities. In a 1966 confidential report submitted to the Office of Economic Opportunity, the NC Fund Low-Income Housing Demonstration Proposal indicated that, “[t]he total number of families already displaced and to be displaced by GNRP [General Neighborhood Renewal Program] projects and other governmental action by July, 1967, is 1,338: 306 white families, and 1,032 non-white families.” The urban renewal project largely served to further the racial housing segregation that redlining in the 1930’s had sanctioned.

Map shows 1937 HOLC’s redlining map overlaid on most current Census data for Durham County.

The fact that these disparities between Downtown Durham and East Durham are still so drastically visible is highly concerning and warrants cause for action. The first steps to addressing this legacy and continuation of racial discrimination are awareness and acceptance of responsibility on Duke’s part.

On my tour around Duke, the guide only showed me the parts of Durham that Duke wanted me to see: the “foody” restaurants, the tree-lined streets, the thriving parks. Duke took pride in the exclusively high-end areas of Durham, but failed to mention the areas affected by gentrification and housing segregation. I am sure many of my Duke peers have graduated without ever stepping foot outside of downtown Durham, often believing that they have experienced Durham and gotten a feel for the city—when in fact they have only gotten a feel for one version of the city, despite that another part of Durham exists. This is even more problematic because it is Duke’s very presence in Durham that helps to perpetrate historical inequality that is still obvious today.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Just because Duke doesn’t seem to acknowledge communities like East Durham doesn’t make them any less a part of the city Duke calls home. If Duke wants to claim the perks of Downtown Durham, it has just as much an obligation to claim its role in the inequality endured by East Durham, in which it has played an active role.

The Duke Office of Civic Engagement states in their 2017 Civic Action Plan that “more than 40 percent of civic engagement activities take place in Durham.” But how many of those programs are based in East Durham communities, where initiatives are needed the most? The answer: not enough.

According to the Duke-Durham Neighborhood Partnership website, “The DDNP serves the 12 neighborhoods surrounding Duke’s campus with a focus on affordable home ownership, educational achievement, youth outreach, neighborhood safety, and quality health care.” Duke civic engagement in Durham neighborhoods has centered largely in Southwest Central Durham, Crest Street, Trinity Heights, and Walltown—all neighborhoods that practically touch Duke’s campus. That isn’t to say that Duke doesn’t have civic engagement programs in other parts of Durham, but programs at the moment are concentrated in the neighborhoods closest to Duke’s campus. It seems that proximity is intertwined with institutional attention—when problems are closer to home, Duke acts on the pressure to care about them.

Duke should prioritize civic engagement programs in East Durham rather than focusing almost entirely on the immediate areas surrounding Duke’s campus to the exclusion of other areas. These initiatives could include school partnerships, advocacy for affordable housing or supporting the Durham Community Land Trustees. In no way should Duke reduce programs in other Durham neighborhoods, but the institution needs to extend efforts more than a bit further beyond the East Campus wall. The Duke community has ample power and resources to help an area that has been continuously neglected—it is time that we use them.