Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” celebrated its 200th birthday this week with a two-part symposium focused on questions of science, ethics and responsibility. Hosted by Duke Science & Society — an organization that explores the ethical, legal and policy-related questions raised by science and technology — the symposium began last Thursday with a panel discussion on Frankenstein’s many film adaptations, lovingly nicknamed “Frankenfilms.” Marsha Gordon, a film studies professor at N.C. State, Deanna Koretsky, an assistant professor in English at at Spelman College, and Misha Angrist, Duke Science & Society senior fellow, traced the creature’s cinematic history from his first appearance in 1910 to modern representations like that of Tim Burton’s 2012 film “Frankenweenie” (2012).

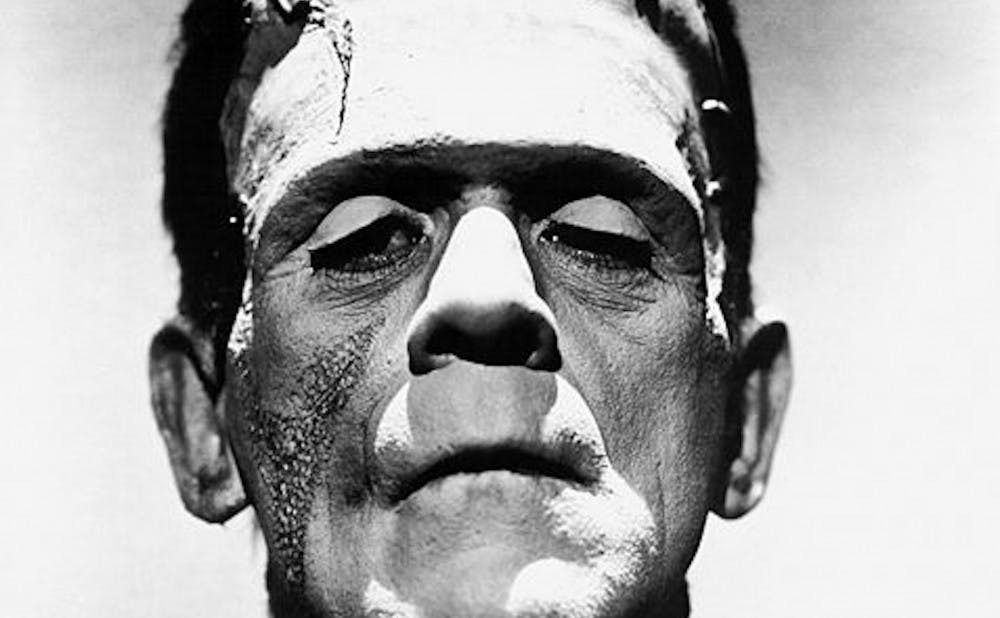

The panel set out to show how we can trace cultural, social and even scientific attitudes through the decades by examining the film adaptations of Shelley’s story. Contrary to the green-skinned, bolt-necked creature we now recognize as Frankenstein’s monster, the original filmic depiction of the creature more closely resembled a hairy caveman — assembled not from amputated limbs but from a mixture of substances in a cauldron. The next adaptation was Universal Pictures’ 1931 “Frankenstein” featuring Boris Karloff. This film not only codified the creature’s appearance but added plot elements that would become hallmarks in future films including the lab set-up and the lab assistant character. This incarnation of Shelley’s story hints at one of the novel’s primary underpinnings — the loneliness of solitude and the human desire for total, god-like control — but leaves much of the novel’s seriousness and contemplation of human nature behind.

While none of the Frankenfilms offer as comprehensive and intricate a story as Shelley’s original novel, they do end up raising interesting questions about gender and race. Although she was the daughter of the early women’s rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft, Shelley’s own gender politics are regressive by today’s standards, yet seem to be headed in a forward-looking direction. None of the female characters in Shelley’s novels have a happy ending — they all wind up dead. But both films “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935) and “Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein” (1994) take Shelley’s gender representation several steps backward. In these films, the female creatures created to cure the monster’s loneliness are reduced to horrific monsters without language or free will. Their sole purpose is to free the original creature from his distress and thus they have very little autonomy themselves. In keeping with Shelley’s tradition, these female creatures don’t live lives any of us would envy.

Equally problematic is the blaxploitation film “Blackenstein” (1973). During the 1970s, Hollywood realized that it could make money off of black people by including them as main characters in films. Though these films featured the first appearances of black Americans in primary roles, the characters they played still often fulfilled stereotypes about the black community. Made the same year that recombinant DNA was discovered, the film combined the horror, comedy and exploitation genres with a scientific spin. In this film, the creature is the result of recombinant DNA treatments gone wrong — a plot element that perhaps reflects the fear of the potential for this new scientific development at the time.

Despite the ways in which Shelley’s novel has been distorted, exaggerated and manipulated, it has formed the basis for a whole lineage of films and ideas of which we still see contemporary incarnations. Films like “Gattaca” (1997), “Jurassic Park” (1993) and “X-Men” (2000) rely so heavily on the themes Shelley proposes that it’s difficult to say that they would have been possible without it. We still see filmmakers raising the same questions of responsibility and the relationship between creator and creation today. It’s not likely that we will ever stop grappling with these questions, or that we will ever cease to find new ways to talk about them. But it is thanks to Mary Shelley and her monster that we are able to have these discussions in this way — through the eyes of an egomaniacal scientist and his doomed and lonely creature.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.