“Turbobob” is the license plate on the 2012 Nobel laureate’s car.

Dr. Robert Lefkowitz has been using the special plate since the mid-1980s when he bought his first fast car—a red 1986 Porsche 944 Turbo—as a reward to himself for successfully cloning the beta-adrenergic receptor, determining its amino acid sequence, and revealing the existence of what would turn out to be the largest family of cell receptors.

After having his Porsche for a decade or so, Lefkowitz traded it in for a BMW M3, which was not turbo-charged. This left Lefkowitz with a tough question.

Should he keep his vanity plate, “Turbobob”?

“I put it to the group during a lab meeting, and the consensus was that the ‘turbo’ referred to me, not the car, so that I could keep it,” Lefkowitz said. “And so I did, and I have it to this day even though I’ve never had another turbo-charged car.”

Pre-Nobel or post-Nobel, Lefkowitz has no intention of slowing down.

A scientific giant

The 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was shared between Lefkowitz and his mentee Brian Kobilka for their ground-breaking research on G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). For Duke, where Lefkowitz has worked since the 1970s, it was the University's first Nobel.

Lefkowitz is also a member of nearly every prestigious chemistry or medicine institute out there, and has too many titles and major scientific awards to list. The award that stands out the most is, of course, the Nobel. It's a recognition of his decades of commitment to researching receptors, which led to discoveries that form the basis of an estimated 40 percent of all prescription drugs.

His humble personality makes it easy to forget that the GCPRs he discovered regulate almost all known processes in humans.

“In fact, over the last decade or so, we’ve actually discovered whole new mechanisms by which the receptors work and, accordingly, a whole new way to make drugs,” he said.

Fifty years ago there was no way of studying receptors, and people doubted they even existed. Lefkowitz’s research revealed what this huge family of receptors look like. Many drugs—including antihistamines and beta blockers—are based on his team’s work and used the techniques they developed.

An article published in Nature magazine in Oct. 2017 called “Trends in GPCR drug discovery" said that 34 percent of all drugs approved by the FDA act on 108 unique GPCR targets. In addition, “drugs that target GPCRs also account for 27 percent of the global market share of therapeutic drugs, with aggregated sales for 2011–2015 of about $890 billion” and “56 percent of GPCRs that are yet to be explored in clinical trials have broad untapped therapeutic potential, particularly in genetic and immune system disorders.”

'Lefkotime'

Minjung Choi, a Ph.D. candidate in biochemistry who joined Lefkowitz’s lab in 2013, described herself as a tortoise and Lefkowitz as a “cheetah on steroids.”

“If she thinks I’m a cheetah on steroids now, she hasn’t seen anything,” Lefkowitz said. “Trust me, she has not seen anything. Nobody who works with me currently has seen what I was like in my prime.”

When asked about his sprint-paced marathon of life, Lefkowitz said, “It’s just who I am.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“Everybody’s different, and I basically only have one speed,” he said. “It used to be 160 mph, but now it’s about 120.”

“He is in the lab doing now what he did 10, 15, 20, 30 years ago,” said Dr. Howard Rockman, cardiologist at Duke and friend of Lefkowitz. “That’s him.”

If it wasn’t for age getting to him, he would still be at 160 today.

The average person’s life is at 20-60 mph, but “Lefkoville” runs on “Lefkotime"—which he defines as “sooner rather than later.”

Lefkotime is, to the average person, the speed of light. But relative to him, alluding to Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, Lefkotime is a peaceful speed, no different than the speed of you or me.

“I do a lot of pestering because very few people are keeping up with Lefkotime,” he said.

Living in Lefkotime means that everyone else on the outside seems slow.

“Sometimes if my trainees don’t do a task in a timely way, for example writing a draft of a paper, I might start writing it and quite literally shame them into getting going,” he said. “I hadn’t done that in years. Why? I have just as much reason to do it as ever because they still drag their heels sometimes…There’s a paper I’ve been really pestering my guys to write, but it’s just not happening on Lefkotime. It’s not even any version of Lefkotime. So over this past weekend I wrote the introduction and sent it to them.”

Lefkotime is so fast that even the most hardworking and brightest researchers can’t help but disappoint occasionally. But that disappointment is neither personal nor offensive. Choi explained that Lefkowitz’s high expectations do not mean he expects everyone to be like him, he just wants to bring the best out of everyone.

“[Lefkowitz] always says he wishes that everyone in their time in his lab achieves their personal best in their life,” Choi said.

The mentor

His ability to make time for students and mentees comes from his focus and discipline, rejecting everything outside his priorities.

“I guess he learned the art of saying no,” Choi said.

Choi said that Lefkowitz never cancels meetings, usually replies to emails in half an hour and always makes himself available to his mentees.

“I feel a very deep responsibility for anybody who works for me for whom I’m a mentor,” Lefkowitz said. “It’s much the same thing I feel for my children and my friends.”

Choi also described her nearly six years in the “Lefkolab”—Lefkowitz’s website is lefkolab.org—as being the most formative years of her life.

In September 2012, Choi made plans to do research with Lefkowitz. Once the call about the Nobel Prize came in October, Choi was worried that Lefkowitz would change his plans because of the Prize. He didn’t, and Choi is graduating next spring—and getting married.

“[Choi’s] having two weddings—one in Korea and one in India—but I’ve added a third,” Lefkowitz said. “We’re going to have a wedding here during a lab meeting where I will be the officiator. Of course, that’s the most important one.”

Rockman noted that what makes Lefkowitz stand out from his colleagues is his devotion to his trainees.

“He probably has the most total number of trainees," Rockman said. "He maintains contact with almost all of them.”

Lefkowitz has trained generations of scientists, many of whom are world-renowned and making their own discoveries.

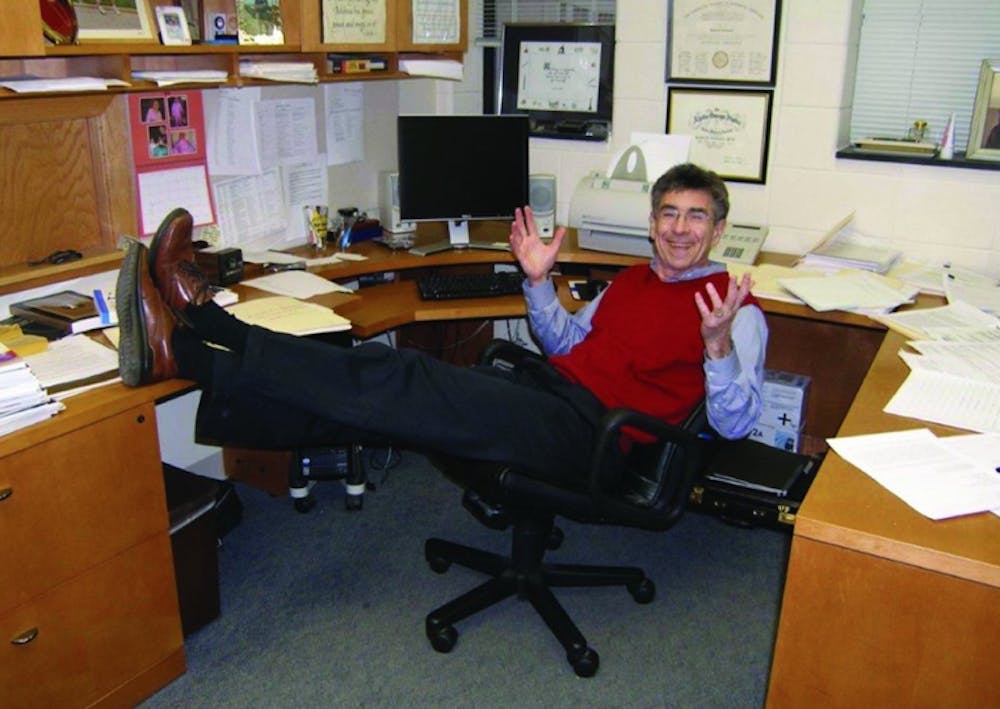

The angle of his office door shows his availability. An open door is an invite in, a partially closed one means you should think twice about it. A closed door says you should talk to the secretary and set something up for a few hours later.

It’s not that he has extra time on his hands—he makes time for these meetings by continuously interrupting himself.

“Everybody is interrupting everybody,” Lefkowitz said. “I’m used to dealing with that fragmented kind of time thing.”

There’s never a slow day in Lefkoville.

“Donna [former secretary for Lefkowitz for 42 years] said that you’ll have some days where you’ll have not a lot to do, and it’s been a year now and I’m waiting for that day,” said Joanne Bisson, his current administrative assistant. “What was she talking about?”

People who work in his lab are not the only ones he makes time for.

Senior Young Re Song, a residential assistant in a first-year dorm, scheduled for his residents to have lunch with Lefkowitz. After the one-hour luncheon, first-year Connor Passe described Lefkowitz as "a nice grandpa”.

“It’s so cool that one of [Lefkowitz’s] favorite memories is when he came out onto the court in Cameron [Indoor Stadium] and people started chanting ‘he’s so smart, he’s so smart, he’s so smart,’” Passe said.

Lefkowitz’s two favorite things are hung up side-by-side in the center of his office—the jersey presented to him by Coach K and the Nobel Prize.

'Backup plan? No, absolutely no'

Dr. Ralph Snyderman, former dean of the School of Medicine and Lefkowitz's best friend of 40 years, said Lefkowitz had that “fire in the belly to go all the way [with his research].” The researcher was never distracted by the offers to be a dean or a chair—his laser focus was on his receptors.

“Bob, if nothing else, is incredibly persistent,” Snyderman said. “If he gets onto something he does not stop, and that’s one of the reasons he won the Nobel Prize.”

Lefkowitz’s focus stems back to age eight when his family physician became his role model.

“Backup plan? No, absolutely no,” Lefkowitz said. “Never a plan B or a plan C. I was going to be a doctor, a practicing physician and that never wavered. It was my calling.”

The Vietnam War steered Lefkowitz away from being a cardiologist and into research for the National Institutes of Health. He served at the NIH from 1968 to 1970 as a commissioned officer in the United States Public Health Service to fulfill his draft obligation.

“It was an abject failure for 18 out of 24 months,” Lefkowitz said. “I was quite convinced I was not cut out for research.”

'He’s the easiest guy in the world to talk to'

At almost 75 years old, Lefkowitz still works full time, getting into his office at 10 a.m. and leaving at 6:30 p.m. each day.

He wakes up at 6 a.m., reads the New York Times for 45 minutes, works out in his home gym for an hour, meditates, showers and has breakfast.

After work, he eats dinner with his wife, and then gets back to work again after dinner, keeping an eye on a muted CNN. He finally goes to sleep around 10 p.m. after reading some non-work-related books.

“The basement of my home is equipped as a gym and it’s at the level of a professional exercise club,” he said. “The only time I use the treadmill, which is my favorite machine, is on the weekends.”

His weekends are scattered with more workouts, time with friends and catching up with his kids by phone or FaceTime. He refers to his weekend workout of using the elliptical, treadmill and recumbent bike as his “mixed grill.” He doesn’t run outside anymore, but he and Snyderman used to run together six days a week—a 10k during the week, and 10 to 15 miles each day on the weekend.

“He’s the easiest guy in the world to talk to,” Snyderman said. “So we got to be friends.”

Now that both of them are in their 70s, they've traded in the weekend runs for Sunday coffees.

“We meet at my house every Sunday for two hours and during the summer, we’ll sit in rocking chairs on my porch,” Snyderman said. “We’ll sit for two hours sipping our coffee, talking about usual things—how you’re doing, how’s your life, Duke, Duke athletics and politics.”

Lefkowitz’s intensity and passion for science shines through even in his exercise regimen.

“You may think I’m a little compulsive as I document my exercise data each day,” Snyderman said. “But whatever I do, Lefkowitz does 10 times more. Bob records everything possible that can be measured and keeps it in a journal that he constantly refers to so he can check how he’s doing… Bob and I say we’re exactly alike except he’s 10 times me.”

Lefkowitz keeps an actual lab notebook to log his workout data. Each notebook lasts him 2.5 years.

“I’m going to continue doing what I’m doing, and I’m still every bit as enthusiastic as ever,” Lefkowitz said. “To me, it’s like my treadmill.”

At age 74, Lefkowitz’s best pace is a 10-minute mile on his treadmill for relatively short distances. He and Snyderman used to run eight-minute miles for long distances and six to seven-minute paces for races.

“So I’ve slowed down, but as I say to the people outside the rocket ship, it looks like I’m still moving at light speed,” Lefkowitz said.

'Time' for a personal life

But no one’s life can be all optimism and on Lefkotime—not even a Nobel Prize winner’s.

Even someone with an uncanny level of discipline and focus has parts of life he can’t control.

“I’m extremely focused in my professional and personal life,” Lefkowitz said.

He lost focus only in times of extreme emotional stress—his 1989 divorce and his 1994 coronary artery bypass surgery, which he described as the “two main crises of my adult life.”

“I was just hanging on, trying to get through the day,” Lefkowitz said. “Fortunately those days passed.”

There have been times in his life where he has done things he didn't think he could accomplish, like coming to grips with challenging personal circumstances like his divorce.

How did he finally come to a place of total acceptance?

“Time,” he said.

With his dedication to his research, Lefkowitz didn’t have as much time to spend with his five kids as he might have liked.

“When I look back on it, yeah, I was not like one of these fathers who was at every little league game, but I did some of them of course,” he said. “The question is—do I have regrets about it? I would say not really. Well, why not? I guess it’s just not who I was."

He met his first wife Arna when they were 15 and 13 at summer camp. They started dating when he was 17, got married at 20 and had their first child at 21. They share five children and are both remarried.

"At some level, I made a choice. It didn’t feel that way. I always felt like I was just doing [my thing], just being me," he said. "In other words, if I had to do it all over again, I think I probably would do it the same way."

Lefkowitz has lived life with few regrets.

“There have been things that happened to me in my life—divorce, etcetera—that I wish perhaps had not happened." he said. "But no, I have no real regrets."

“Sometimes when I’m leaving for work in the morning, my wife will say to me ‘what’s cooking in your day today?’” Lefkowitz said. “I’ll think about it, and then as I’m getting up to leave, I say ‘I’m off to be the wizard, the wonderful wizard of Bob.'”

Lefkowitz only takes one true vacation a year—a week at the beach with his wife Lynn Tilley, their kids and their grandkids.

He and Tilley enjoy traveling together for his work. Lefkowitz rarely goes out of his way to travel unless it’s work related. He’s never visited Poland where his grandparents are from, but he’s excited to visit this year for a scientific conference. His grandparents immigrated to the U.S. in the early 1900s, but many of his relatives perished in the Holocaust.

“Also this is going to be difficult, but it’s something I’ve had on my bucket list for a long time,” Lefkowitz said. “We’re going to visit Auschwitz, the concentration camp.”

'The most authentic me I can be'

Lefkowitz has reached the pinnacle of his field. Now, his professional goals are “fightin’ the good fight, doin’ the good science and having fun mentoring my people.”

His personal goal is to “be the most authentic me I can be.” Lefkowitz said that the older he gets, the less need he feels to impress people and put on airs. Instead, he wants to enjoy the wisdom he has gained over the years.

“I would say this is the most comfortable I’ve been in my own skin, not that it was ever particularly uncomfortable," he said. "I kind of like being me. I enjoy it. I find myself a fun person to be around. I enjoy myself. It’s kind of fun. I enjoy playing Bob Lefkowitz in this movie we’re all making every day.”

He noted the speed at which modern science is developing. Lefkowitz said that he has little doubt that 50 years from now practitioners will be surprised at today's practices, like bypass surgery.

“I would love, one of my fantasies, would be after I’m dead and gone, every 25, 50 years, I could come back just for a day or two just to see what was going on in science and medicine and how it moved forward,” Lefkowitz said. “That’d be a cool thing."

Nobel Prize—now what?

“I think [the Nobel Prize] is a really nice validation of a lifetime of work,” Lefkowitz said. “Everybody likes to feel appreciated… But I’ve never taken it too seriously.”

Nobel or not, Lefkowitz is going to keep running on “Lefkotime” in the “Lefkolab."

He made a pact with himself after he won that he would not let the prize change how he lives his life. The scientist has absolutely no plans to retire. He was recently in a car accident that totaled his car, but it’s for certain that he’s keeping his license place “Turbobob” for his new car.

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute funds most of his research. The funding renewal every five years is an extremely rigorous process, and the “Nobel Prize is no guarantee of success.” In 2021, he’ll have the option to not stand for review and take a five-year phase out. If he stands for review, he’ll have funding until he’s 89.

“We’ll see what happens,” he said.