Panelists at a discussion Thursday afternoon discussed the links between the philosophies of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., two historical figures who represent the success of nonviolent civil disobedience in overturning a society’s unjust status quo.

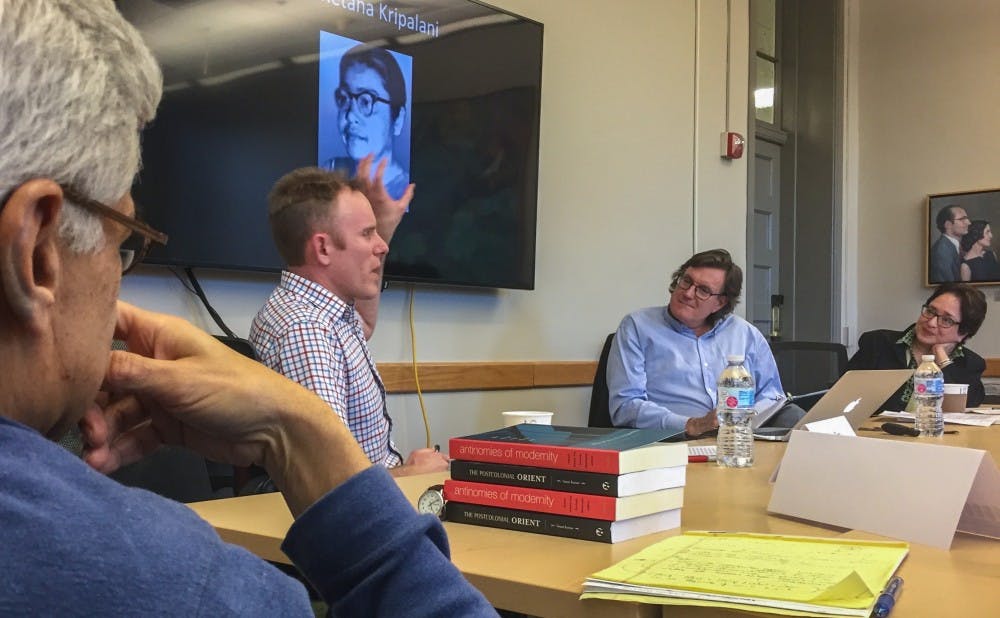

Co-sponsored by the Kenan Institute for Ethics and the Duke India Initiative, the panel included Thomas Jackson, professor of history at the University of North Carolina Greensboro, and Nico Slate, professor of history at Carnegie Mellon University. The two also touched on other historical figures who had been influenced by and made connections between civil rights matters in the United States and the plight of Indians under British rule.

Jackson was the first to speak, emphasizing how King’s religion informed the values he preached. He described “the social gospel that [King’s] father delivered” as the foundation for King’s own beliefs. King's advocacy for the poor and the oppressed was very much in alignment with what Jackson referred to as “Gandhian values.”

He added that, by some accounts, King’s favorite book was That Strange Little Brown Man Gandhi—a biography and analysis of Gandhi’s life by the bishop Frederick Bohn Fisher. In 1949, while enrolled in seminary school, King submitted an assignment for a theology course in which he named Gandhi along with Jesus of Nazareth as one of six figures personifying the mission of Christ. In Jackson’s view, King admired Gandhi for his renunciation of material possessions and, by extension, of his status as a member of one of India’s higher castes.

“King was impressed that millions of Indians who had not touched each other for thousands of years were now singing and praying to God together because of Gandhi,” he said. “King said to his wife once that he didn’t need a house or family, realizing those obligations prohibited him from taking a life of poverty like Gandhi had.”

Slate followed up Jackson’s analysis by naming and describing the views of lesser-known figures who represented a similar kind of bridge as between King’s and Gandhi’s respective campaigns. Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, for instance, was an Indian social reformer who visited the American South in the 1941 and identified herself to a demanding train conductor as a person of color “instead of a prominent foreign figure who’d just had tea with Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House.”

A year earlier, Pauli Murray, an African-American civil rights activist, drew an analogy in the form of a hand-scribbled chart between the social struggles of black people in the U.S. and those of Indians against the colonizing British in that era. Slate called this his "favorite historical document ever."

“Murray’s analogy is only one of two potent analogies that have linked black struggles to India,” Slate said. “One is the race-colony comparison of all Indians with African-Americans. This is predated by comparisons between India’s lowest caste, the ‘untouchables’, and African-Americans.”

Slate and Jackson concluded the discussion with a Q&A session that addressed the relevance of Gandhi and King’s approaches to human rights today.

“Movements today don’t need Kings,” Slate said, explaining how the new tools of social media offer a cohesion to contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter that only a human figure could offer in King and Gandhi’s time.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.