Successful diplomacy requires a sufficient understanding of the past and one’s opponents, a historian and former foreign policy consultant said during a talk Thursday.

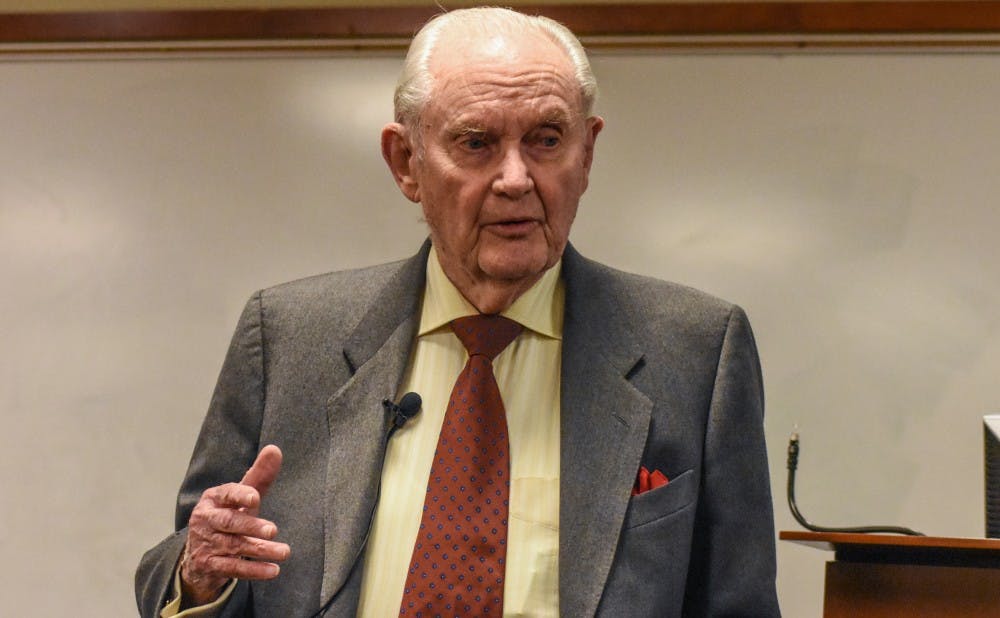

“For some reason, [for people in foreign countries] we are no longer regarded as a friend, a patron, an ally or a donor to their way of life,” said William R. Polk, former professor of history at Harvard University and the University of Chicago, who also served on the State Department’s Policy Planning Council under President John F. Kennedy.

Americans were very popular in other countries several decades ago, Polk said, recounting his own experience abroad.

“When I was a young man, I travelled all over Africa and most of Asia and anywhere I went, it was very dangerous,” Polk said. “The danger was that when I arrived at a little village, everyone was ready to fight to see who could entertain me, who could feed me and take care of me. ”

In contrast, Polk said, an antagonism toward the United States is growing all over the world nowadays.

Polk addresses this change in attitude in his new book, "Crusade and Jihad." He suggested that the reason behind this phenomenon is the terrible reputation for colonialism that the United States inherited from other countries in the Global North, such as the United Kingdom, France and Russia, referring to the United Kingdom’s invasions into Afghanistan and France’s colonization of Algeria in the nineteenth century.

Colonization is an abstract idea for most Americans because the United States did not directly participate very much in modern colonization, Polk said. However, American ancestors acted like colonizers when they seized land from indigenous Indians, he noted.

Polk explained that the first governor of Massachusetts set up and proclaimed the colony of Massachusetts as the city on the hill, which gave the light of reason, peace and happiness to the whole world.

“But he failed to mention that the word ‘Massachusetts’ was a native Indian word which means ‘the high hill,’ a hill that Americans stole or captured from the Indians,” he said.

International tension from history is reappearing in a different form, Polk added. But he said the solution to many of these problems also lies in the history.

“Since World War II, the United States has been increasingly moving away from diplomacy—away from trying to understand other people—toward militarization,” Polk said. “Today we are deeply affected by this shift.”

For Polk, diplomacy is not about giving and enforcing commands. Without understanding what the opponents think about and care about—even if they disagree with the United States’ proposals—a conflict can never be resolved efficiently, he explained.

He added that military actions often lead to a major transformation in relations between countries, as well as the deaths of a large number of people. For example, he pointed to the United States’ forceful overthrow of the Saddam Hussein government in Iraq, which may have served U.S. interests, but also incurred huge costs on both countries.

The founding fathers of the United States were especially concerned with the abuse of force, Polk said. They therefore built into the Constitution various provisions to guard against this issue, including no appropriation of money for the military use for more than two years, keeping the military under civilian control, maintaining a small armed force and the establishment of separated state militias as a balance against the army.

However, Polk noted, many of the provisions are no longer carried out today.

He said empathy is also critical in diplomacy. For example, some Somalian fishermen became pirates partly because large fishing industries overfished in the waters where they used to harvest and significantly endangered their livelihood, Polk noted.

“I think under these circumstances, I would have done the exact same thing,” Polk said. “If we can occasionally put ourselves on the other side of the table, I think we are more likely to come up with relatively reasonable policies.”

Many diplomats nowadays and in his time did not recognize or have any interest in how previous events led to today’s conflicts, Polk said.

“[As a former cowboy], I used to tell my colleagues at the State Department that many of them had an axiom, which was ‘Ready, Aim, Shoot,’” he said.

With a genuine understanding of the evolution of a problem, Polk noted a crisis may not even arise from the very beginning.

Ke Xu, a graduate liberal studies student who attended the event, said that as a historian, Polk demonstrates a more continuous and macroscopic aspect of international issues.

“[A primary takeaway from Polk’s talk is that] adopting violence does not mean a country is powerful,” Xu said. “The real power is being able to resolve the conflict, for which diplomacy is in need.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.