Mike Krzyzewski has stayed in Durham since 1980, when he was hired as Duke’s head coach at age 33. With a 99-69 win against Utah Valley, he has now won 1,000 games with the Blue Devils in the last 37 years. This is the story of the group that got him his first 17 victories.

The 1980-81 Blue Devils were coming off an Elite Eight appearance the year before, but lost head coach Bill Foster to South Carolina and lost first-team All-American Mike Gminski to graduation and a 14-year NBA career. Krzyzewski’s first team went 17-13 and advanced to the NIT quarterfinals—he didn’t take Duke to an NCAA tournament until 1984.

The players on that 1980-81 team went on to make careers as surgeons, consultants, investment bankers, professors and coaches themselves. The Chronicle caught up with most members of the team to discuss their first impressions of Krzyzewski and what they are up to now.

Kenny Dennard (Senior in 1980-81)

Dennard found out Duke hired Krzyzewski when the unfamiliar name appeared on TV at a bar in the Florida Keys after his junior season.

It wasn’t during spring break—that had already happened when basketball season was still going on—but Dennard always took a vacation anyway whenever the season ended.

“I would take my own spring break after the season every year. Obviously, we rationalize everything, but I didn’t think of it as a real burden to get a couple weeks off after putting in all that time for the Duke University Blue Devils,” Dennard said. “This was before people really cared about if you went to class.”

Dennard said his co-captain, Gene Banks, was also taking a personal spring break in Philadelphia at the time, so neither of Krzyzewski’s rising senior leaders were in town to meet him when he took the job. But Dennard got on the road when he saw the news and took about a week to make his way back to Durham and meet his new coach.

“A lot of people were nervous because Gene and I were somewhat considered carefree and fun-loving. Everybody was worried that his Army style was going to cramp our style, but he was great,” Dennard said. “Coach K put up with us.”

Dennard started every game as a senior, averaging more than 10 points and leading the team in rebounds, before a three-year NBA career.

Dennard beat testicular cancer during his pro career and served on the board of Coaches vs. Cancer for more than a decade. He founded his Houston-based Dennard Lascar Investor Relations firm 20 years ago and is now its CEO. The firm helps companies communicate with Wall Street by writing press releases and making slide shows, among other public relations strategies.

Dennard still returns to Duke every year for the game against North Carolina at Cameron Indoor Stadium and usually gets to a few other games, and is a guest at the K Academy fantasy camp every summer. He also stays connected to Duke with his Texas license plate that says “GTHCGTH”, and has made it a goal to get a license plate with that acronym in every state, even starting a spreadsheet to track its progress a few years ago. More than 20 states are checked off the list.

“Once you get it, you represent the whole state. We had about 150 million people that we represented with the ‘Go to hell, Carolina, go to hell,’ tag,” Dennard said. “The funny part about it is, when you file an application like that, they call you and ask you what does it mean, so they don’t allow vulgarity or certain things. I said it’s ‘Get that hat, cat, get that hat.’”

Gene Banks (Senior)

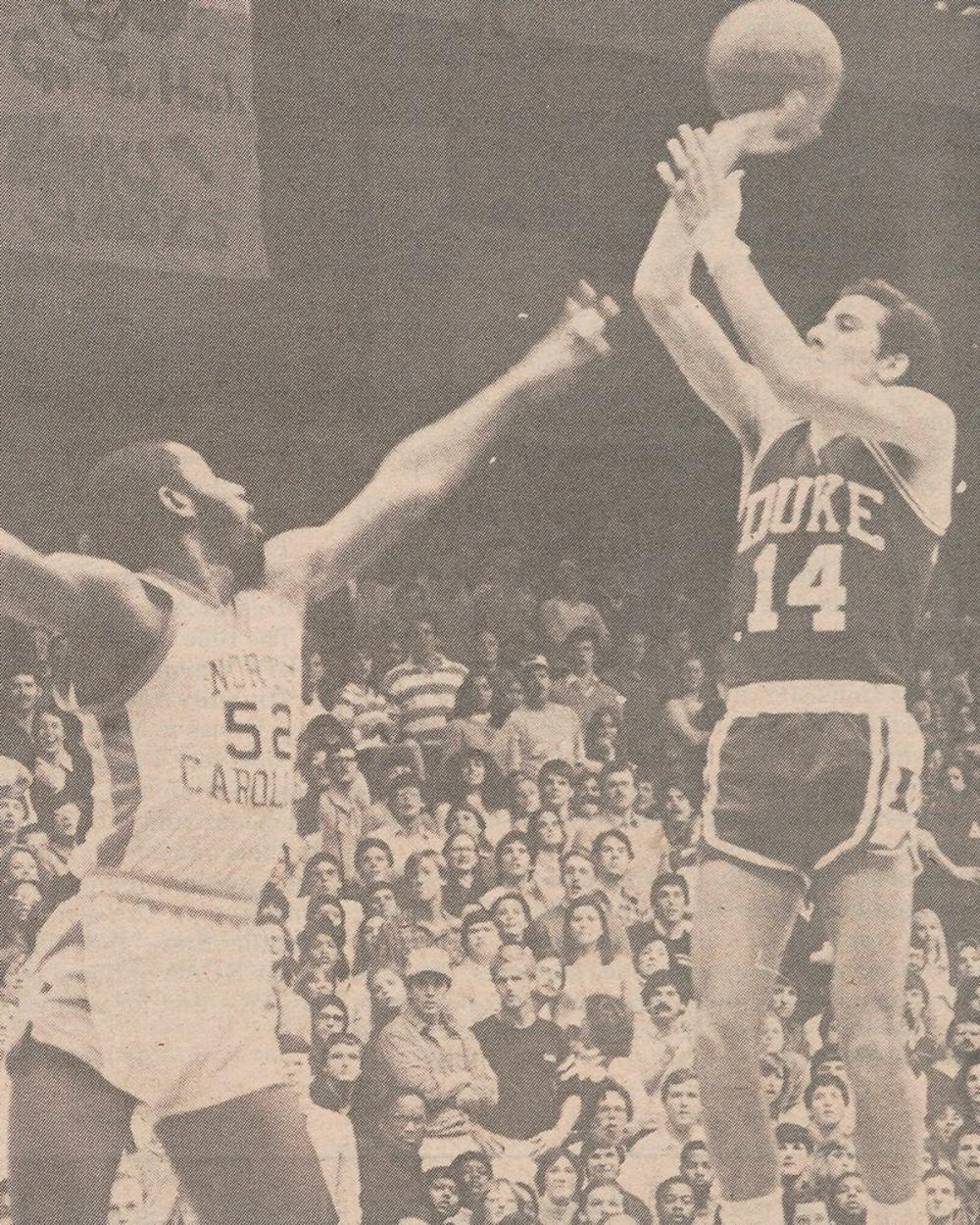

Banks was Duke’s leading scorer and was the man responsible for one of the first and most memorable moments of the Krzyzewski era at Cameron Indoor Stadium against North Carolina Feb. 28, 1981.

After handing out roses to the student section when he was introduced on Senior Night, Banks took a long pass from Dennard with one second left in regulation and swished a 20-foot jumper to send the game to overtime. His putback in the closing seconds of the extra session lifted the Blue Devils to a 66-65 win for Krzyzewski’s first victory against the Tar Heels.

“That game epitomized me saying to him, ‘Thank you,’ for what he was doing. I wanted him to get off on a good foot,” Banks said. “It was probably one of the greatest moments of my career.”

Banks has stayed involved with Krzyzewski’s program since he graduated and spent 12 years playing in the NBA and overseas. He still comes back for the K Academy fantasy camp during the summer with dozens of Krzyzewski’s younger former players.

“I’m very honored that he considers me a part of the family. I’m known as the godfather to all those guys,” Banks said.

Banks spent time coaching and scouting for the Washington Wizards and is now a special consultant for China’s pro basketball league. He spends 30 days in China every two to three months, training some of the league’s big men, and splits the rest of his time between Greensboro, N.C., and Philadelphia running the Gene Banks Foundation to empower underprivileged youth.

Jim Suddath (Senior)

Suddath had a spring and summer of misfortune in 1980.

He tore his meniscus against Maryland during his junior season, Foster’s last year at the helm, and played through the injury the rest of the year. He only underwent surgery after Duke was knocked out of the NCAA tournament. When Krzyzewski was hired in March 1980 and met with the rising seniors on the team in athletic director Tom Butters’ office, Suddath walked in on crutches.

After rehabbing through the rest of the school year and working a summer job in Washington, he noticed his knee was starting to hurt again in August, and he moved into school early to have another surgery to repair his cartilage. Krzyzewski visited him in the hospital the night of his operation.

Suddath was finally fully cleared to play on the first day of official practice in October, an open practice in front of thousands of fans in Cameron. But that didn’t go according to plan, either, as he said his knee locked up and threw him to the ground eight times.

“So the first time Coach K saw me, I was on crutches. The second time he saw me, I was in a hospital bed, and the first official time in a practice uniform on the court, my knees locked up on me and I kept falling down,” Suddath said. “They put me right back in the hospital that night and did this new thing called arthroscopic surgery.”

Suddath eventually recovered and battled his way back onto the court, appearing in 24 games and even starting three times toward the end of the season.

“You’re a brand new coach.... You’ve got a senior white guy, a half step slow, that’s done nothing but have knee problems the whole time. What do you do with him?” Suddath said. “He did not throw me away. Many other coaches might have done that. They might have just written me off, but he did not.”

Off the court, Suddath was the president of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes as a senior and went on to become a pastor in the church ministry for about 25 years at three different churches. When Foster died two years ago, Suddath officiated the funeral for his former coach.

Now, he is a bible teacher, coach, dorm parent and chaplain at the McCallie School, an all-boys boarding school in Tennessee. He coaches the JV golf team and also serves as a practice coach specialist for the basketball program.

Chip Engelland (Sophomore)

Currently the most prominent member of the 1980-81 team, Engelland has gained recognition for knowing how to shoot a basketball and how to teach that skill better than possibly anybody else in the world.

Engelland is widely credited with transforming Tony Parker, Kawhi Leonard, Danny Green and Patty Mills, among others, into lights-out shooters as an assistant coach for the San Antonio Spurs since 2005, helping the team to NBA titles in 2007 and 2014. As one of the more specialized assistant coaches in the league, he has turned the biggest strength of his playing career into a successful coaching career.

“I knew it wasn’t going to be defense,” Engelland joked. “I always kid Coach K. I scored 1,000 points at Duke but gave up 1,500. That’s not the plus-minus he was looking for. I knew I wasn’t going to be doing defensive clinics.”

But even if he frustrated Krzyzewski with his defensive deficiencies, Engelland always found time on the floor due to his ability to score. The 6-foot-4 guard shot better than 50 percent from the field and better than 85 percent from the free-throw line all three seasons he played for Krzyzewski. When the ACC instituted an experimental 3-point line for the 1982-83 season, Engelland knocked down 55.4 percent of his long-distance attempts as a senior captain.

Engelland’s three Duke teams under Krzyzewski went just 38-47, but he noticed Krzyzewski always had an innate sense of the pulse of his team.

“The one thing Coach was always incredible at from day one—he had an ability to stop a practice and extricate that one sentence that either we needed a little more of this or a little less of this, with the right peppering,” Engelland said. “The timing of that, that’s an art form. He had that day one.”

During the summer while he was in college, Engelland coached the varsity players at his alma mater of Pacific Palisades High School in Southern California during their offseason workouts. One of those players was Steve Kerr, who went on to set the NBA’s career record for 3-point percentage in a 15-year career and is now the head coach of the Golden State Warriors’ dynasty.

Engelland never made it to the NBA and went to law school at DePaul for two years before deciding he liked coaching better. He then held clinics and started to gain respect in the industry for his continuing tutelage of Kerr in the 1990s. Before he took a job on the bench, he became a naturalized Filipino citizen and played for the Philippine national team for three years and then returned to the United States to play in the Continental Basketball Association and the World Basketball League.

“I was a nine-year minor league player, and what you’re trying to do in the minors, you’re trying to learn every trick to make it.... That has really helped me in the teaching part,” Engelland said. “It sure has been fun. I’ve been really lucky.”

Doug McNeely (Freshman)

Krzyzewski didn’t have much time to build a recruiting class for his first season after he was hired in March, but he had been pursuing McNeely while he was at Army and signed him as his first recruit when he took the job at Duke.

McNeely appeared in 16 games as a freshman and eventually captained the 1983-84 Blue Devils as a senior, playing in all 34 games to help take Krzyzewski to the NCAA tournament for the first time.

“The people that have been around the program have all had great integrity and they’re very positive people. I think those are some of the foundations of winning environments,” McNeely said. “When he was younger, there were the roots of that being planted.”

McNeely has spent most of his time since graduating on Wall Street, working for Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and other firms before winding up where he is now as a managing director of BlackRock, an asset management firm.

“I truly believe in my heart that BlackRock is the best of those organizations,” McNeely said. “A lot of the lessons that I learned from Coach K and from my teammates at Duke have helped me to be successful on Wall Street.”

Bobby Dwyer (Assistant coach)

Dwyer was one of the men most familiar with Krzyzewski’s coaching style in 1980 after coaching under him for all five of his years at Army and coming with him to Durham. He was an assistant for Krzyzewski’s first three years at Duke and built strong recruiting relationships with Johnny Dawkins, David Henderson and Tommy Amaker, a core that eventually took the Blue Devils to the Final Four.

“If you’ve been around Mike much, he’s a very, very positive person. That served him and served us well during that time. He was just positive that we were going to succeed,” Dwyer said. “I’m proud to be a part of—a small part—but a part of what’s happened down at Duke under Mike’s leadership.”

At the end of the 1982-83 season, Dwyer got engaged and wanted to start a family, which was not compatible with the constant recruiting trips that were required of an assistant coach at a high-profile program. He decided to leave Duke for the head coaching job at Division III Sewanee and spent two years there before taking a job at William & Mary as the associate athletic director for development. For the last 32 years, Dwyer has been in charge of the Tribe Club, William & Mary’s athletic fundraising arm.

“I had never been a fundraiser.... Mike had a lot to do with me getting the job,” Dwyer said. “He was extremely supportive of me with the athletic director at William & Mary, telling him my skillset would transfer over.”

Jon Weingart (Sophomore)

When Weingart graduated from high school in the spring of 1979, Krzyzewski’s staff at Army talked to him about potentially playing there, but he chose to be a regular student at Duke instead, at least until Krzyzewski followed him to Durham and needed a couple of extra bodies for practice in his first year. Weingart joined the team as a walk-on for one year and scored two points during the 1980-81 season.

“[Krzyzewski] was very intense at that time, probably one of the more intense people that I had ever come across in my first 19 years of life. He was somebody who as I reflect back was very comfortable in who he was,” Weingart said. “The guy has lived an amazing life, met all kinds of people, been in all kinds of incredible situations and yet stayed true to who he’s always been.”

While Weingart was on the team, he applied for a special program for Duke sophomores at the time that guaranteed him admission to medical school at Duke after graduation, and his interview for the program was the day before the Blue Devils’ memorable win against North Carolina in the last game of the regular season.

“The medical school people are all basketball groupies, so the head of the admissions committee looks over at me and says, ‘What did the coach say to you after practice today?’ I looked up at the person and I said, he said, ‘Win,” Weingart recalled. “The person’s eyes lit up, and I said if we win tomorrow, I’m in medical school.”

Whether or not Banks’ heroics the next night helped Weingart get into the program, he took advantage of his graduate education and has made a career as a neurosurgeon at Johns Hopkins. Weingart is also a Duke season ticket-holder, coming to seven or eight games a year, and has two children who graduated from Duke.

Mac Dyke (Sophomore)

Like his roommate Weingart, Dyke was a walk-on for one year while Krzyzewski needed to fill out his roster and scored two points during the season. A 6-foot-7 forward, Dyke had the size to challenge some of the team’s bigger players in practice.

“Everybody wanted to do as much as they could. [Krzyzewski] was a great motivator,” Dyke said. “We managed to beat a very good UNC team in Gene Banks and Kenny Dennard’s last [home] game. That last play was like a predecessor of the Grant Hill-Christian Laettner play years later. He just made you believe. We knew we were going to win that game.”

After graduating in 1983, Dyke continued with Weingart into medical school at Duke and is now a cardiothoracic surgeon in Fargo, N.D., and the associate dean of the University of North Dakota’s medical school. With two Duke degrees and a daughter who graduated in 2010—a month after Krzyzewski’s fourth national championship—he is North Dakota’s representative in Dennard’s “GTHCGTH” license plate mission and said he has been to a few of the Blue Devils’ championship games.

The rest: Starting guard Tom Emma died in 2011 at age 49. Vince Taylor, a current assistant coach under Dawkins at Central Florida, and Mike Tissaw, a psychology professor at SUNY-Potsdam, could not be reached for interviews. Larry Linney, Allen Williams and Gordon Whitted could not be located.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.