Although the wounds are no longer fresh, the Duke community still remembers the lessons of the Duke lacrosse case ten years after its conclusion. Some of them, anyway.

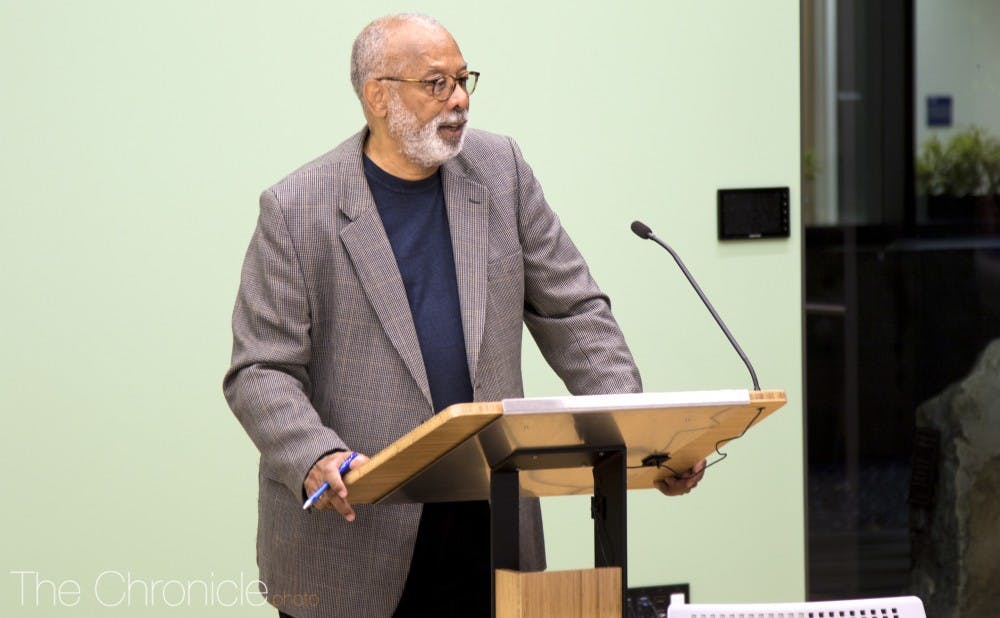

James Coleman, Jr., John S. Bradway professor of the practice of law, illustrated this at a talk sponsored by Duke Honor Council on Thursday night. Coleman addressed possible biases in the police investigation and in the prosecutor’s handling of the case. He also spoke about the findings of a committee, for which he served as chair, charged with investigating the conduct of the lacrosse team in the five years preceding the case.

“I think the case was a miscarriage of justice, but I don’t think it was the greatest injustice in the history of the universe, as some people try to make it out,” Coleman said. “In a world of wrongful convictions, it was an ordinary case of injustice that affected people who were not the usual suspects. That’s what made it different.”

The case unfolded over the course of 12 months, beginning in March 2006 when three lacrosse players were accused of sexual assault by a stripper they had employed at a spring break party. The attorney general, who took the prosecutor’s role in the case, declared the students innocent of all charges the following April.

Coleman said that once involved, he became less concerned with whether the students were guilty—and even thought there was a chance that they were. Rather, he was concerned with ulterior motives he thought could be driving the case—specifically, the motives of the original prosecutor, Mike Nifong.

“Nifong had started to make racially inflammatory statements in circumstances that made it appear as though they were intended for political gain,” Coleman said. “He was running for election as the district attorney in Durham and had never run a campaign before. It looked like he was using this case to gain votes.”

Coleman noted that, had Nifong visited the house on Buchanan Boulevard where the party had taken place, he may have noticed that “the bathroom in the house was very small, unlikely that three people plus the woman would have been able to stand in alone.”

Highlighting oversights in the police investigation surrounding the case, Coleman also explained that its high-profile nature focused it in a direction that caused police to dismiss or obscure facts inconsistent with the rape allegation.

A DNA test taken from the accuser, for instance, produced a positive profile of a male that was not one of the accused players. Instead of presenting this evidence explicitly, the prosecution “tucked it into about 3,000 pages of documents and gave it to the defense.”

However, Coleman also emphasized that the role of his committee was not to investigate the criminal charges themselves. Rather, he was responsible for probing claims made in the press about the lacrosse team’s supposed general misconduct.

“We looked into the lacrosse team’s behavior in the previous five years, relative to that of other sports teams and relative to that of Duke students generally,” Coleman said. “What we found was that they were not different in any significant way from either other teams or from other students, or identifiable groups like fraternities and sororities on campus. The misconduct in which they engaged was primarily the result of drinking.”

Once the students had been cleared of all charges, the case took on a different tone. In Coleman’s view, it transitioned from a criminal case to one concerned with political correctness.

“The case was used as a club to beat on liberal members of faculty at universities and faculty who were people of color, as if somehow they contributed to the false charges being made against the students,” Coleman said. “As a result, I think some of the important lessons about the case were lost. Lessons about how the criminal justice system works, how easy it is to be a victim of false charges and then possibly of wrongful conviction.”

Michael Phillips, a first-year law student, said he took a lesson from Coleman’s talk.

“My big takeaway was that [the lacrosse case] wasn't politically motivated,” Phillips said. “In today's age, when everything feels so politically saturated, it would be easy to look back at something that happened ten years ago and put a political spin on it. We shouldn't do that.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.