It was Spring 2015 and then-sophomore Mera Liccione was leaving for the gym when she fainted in her Central Campus apartment.

Friends thought she was having a seizure, but they were wrong—Liccione’s anorexia nervosa was the culprit. Her thin body had developed an electrolyte imbalance, which was negatively impacting her heart.

“It was the scariest thing I had ever been through,” Liccione, now a senior, said.

For many people suffering from eating disorders, it takes a dramatic breaking point—such as Liccione’s trip to the emergency room—to open their eyes to the severity of their illness.

Eating disorders at Duke

Female students with AN, like Liccione, are not alone on Duke’s campus.

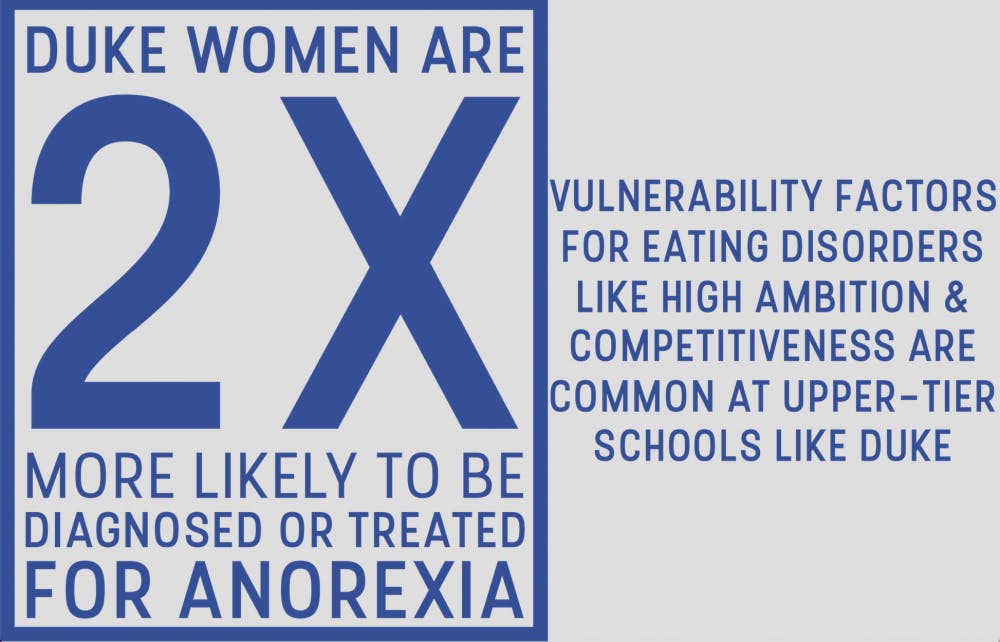

A recent national survey from the American College Health Association found that Duke undergraduate women were twice as likely than students at other colleges to report being “diagnosed or treated by a professional” for anorexia. The number at Duke was more than four percent of women surveyed, compared to less than two percent nationwide.

According to the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, people with AN restrict their energy intake to the point where their body weight is extremely low and they are either very afraid of gaining weight or do not allow themselves to experience weight gain.

Nancy Zucker, the founder and director of the Duke Center for Eating Disorders, said that it is not surprising for schools like Duke to have higher-than-average rates of eating disorders. Vulnerability factors for these disorders—such as competitiveness—are common among the type of people admitted into upper-tier universities.

The ACHA survey also found that female undergraduates at Duke exercise more than their counterparts, doing increased moderate intensity and vigorous cardio or aerobic exercise. However, this raises the concern of whether the exercise represents good health or an unhealthy obsession with exercise.

The DSM-5 does not currently include "exercise addiction" as an addiction disorder because there is "insufficient peer-reviewed evidence to establish diagnostic criteria."

Kim McNally, director of undergraduate studies in the Department of Health, Wellness and Physical Education and a former track team member at Duke, said over-exercise should be measured by its effect on health rather than by the intensity of the exercise.

“If an individual is experiencing signs of overtraining such as recurring injuries, mood disturbance and poor exercise recovery, then they are doing too much,” McNally explained.

McNally also noted that when students exercise so much that it interferes with their academic, career or social obligations, they may have unhealthy relationships with exercise.

In Liccione’s case, exercise was definitely hurting other areas of her life.

Deciding to go on medical leave

Liccione was already battling her eating disorder when she arrived at Duke. The summer prior to her first year, she was so nervous about “measuring up” to her future peers that she began over-exercising and severely limiting her calories.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“[It was] a means of coping with my anxiety,” she said.

Her first year, during a visit to Counseling and Psychological Services, she was diagnosed with disordered eating—a sign of unhealthy dietary habits not yet rising to the level of an eating disorder as defined in the DSM.

“I didn't think at the time that I had a problem,” Liccione explained.

She was not the first person in her family to suffer from this type of issue—her mother is a recovering anorexic.

Soon after her diagnosis, Liccione’s weight dropped enough to meet the clinical criteria for an eating disorder. Still, she refused to acknowledge that she needed help. But early in the second semester of Liccione's sophomore year, one of her friends reported her to DukeReach.

“My friends and professors were starting to get really concerned about how exhausted I was looking, about how malnourished I was looking and that my emotional state was really bad,” she said.

Still, Liccione brushed aside her friends’ worries. She continued to exercise religiously and monitor her meals.

The fainting incident that put her in the emergency room caught her attention. It was then when she realized that she was severely sick and needed help. With some cajoling from her dean, Liccione signed the papers to go on medical leave.

From April 2015 to December 2015, Liccione underwent intensive treatment for her eating disorder, which she described as one of the most difficult experiences of her life. She was sent to an intensive, outpatient treatment center, as opposed to an inpatient treatment center, because her doctors did not want to put her in an environment where she might feel pressured to “be the sickest.”

“As Duke students—and Duke students who have eating disorders—we’re a nasty competitive bunch,” Liccione explained.

She returned to Duke in January 2016 and is listed currently as a member of the Class of 2018, one year behind her original class.

Learning to be open

An undergraduate student—who we will call Emily to protect her identity because of her public status as a student athlete—is no stranger to eating disorders. In high school, her AN was so severe that she nearly died from it.

Emily’s sickness started when her best friend committed suicide. It was after this traumatic incident that she decided the best way for her to deal with her emotions was to control her food. By age 15, she had lost 35 percent of her body weight.

“I was horrendously sick, to the point where I couldn't go to school," she said. "I couldn't do anything."

Yet, Emily still could not comprehend how ill she was. She can recall days when she ripped down her curtains out of frustration because her mother told her to eat a potato.

But, it was ultimately the distress that Emily’s illness caused her parents that led her to seek treatment. Watching her parents break down in sobs as well as her school threatening to kick her out made Emily want to get better.

“I think the biggest thing about recovery is admitting you have a problem,” Emily explained.

In her recovery period, during which she underwent outpatient treatment, she was weighed by a professional every day. She never saw the actual number on the scale; she was always told if her weight went up or down.

“I went from eating very little to eating an incredible amount a day—desserts followed by weight gain shakes followed by desserts,” Emily said. “Every single time I did it, I felt horrible. It was a really bad feeling, but I reminded myself why I was doing it.”

Throughout this trying time, Emily often had to remind herself that just as a sick person needs medicine, an anorexic must eat food.

“There was a lot of pride in [eating more]—every time I felt full, I was like, ‘I’m one day closer to getting better, to getting my period back, to doing my sport again,'" she said.

In retrospect, Emily said that a major aspect of having an eating disorder is being fixated on numbers, whether it’s one’s weight or calorie-counting. After going through her recovery, Emily has learned the importance of intuitive eating. She now knows that if she’s hungry, she should eat a snack, regardless of whether or not the people around her eat one. She has learned to listen to her body.

Emily also explained that many people with eating disorders suffer in silence, but she has found that the best way to combat her AN is to be completely open about it. When she returned to her high school after her treatment, fellow students would ask her how her day was going. She would be brutally honest.

“I'd be like, ‘It’s really sh*t, I tried to eat cake and I couldn't do it,'” she said.

Emily knew that people around her could tell she had an eating disorder, so she decided that she would not try and hide it.

“[That’s] the reason I recovered so quickly,” Emily explained.

Emily also credits her supportive high school friends as a major part of her speedy recovery. Emily considers herself a hyper-social person, but there were some days she refused to go out. During these episodes, her friends tried to convince her to go out with them and when they failed, they simply went to Emily’s house to keep her company.

“Every person has a time in their life when they’re going to feel funny about the way that they look. That’s natural,” Emily shared. “We have to embrace the fact that we can’t feel great every day, but what I’ve had to learn is not to take it out on myself. I have to learn to love myself regardless of what I put in my body.”

Emily has worked to make the lives of people with eating disorders less stigmatized. Back home, she has promoted mental health education in school curriculums.

An uncomfortable conversation

Another undergraduate student on the same team as Emily asked to remain anonymous, so we'll call her Julie. Julie began suffering from disordered eating when she was a junior in high school. It was the recruitment season for college athletics and suddenly her sport “metamorphosed” into something that it hadn't been before.

Everything she consumed had to be perfectly healthy. She refused to let her mother cook for her because it stressed her out too much. Instead, she prepared all of her meals and snacks. She developed night sweats and began putting herself to bed as early as possible, for fear that if she stayed up, she would grow hungrier.

“In my head, I thought I was being perfectly healthy, I thought I was eating enough. This was going to be my path to [my sport] and college success,” Julie explained.

Soon, Julie stopped getting her period. In just two months, she dropped 15 pounds.

As the summer before senior year rolled around, Julie received an offer to join a Duke athletics team and suddenly all of the extreme efforts felt worth it. Yet despite her achievement, Julie grew even thinner and suddenly faced anemia—a decrease in the blood's ability to carry oxygen.

Still, she did not seek help.

The first time it occurred to Julie that she should change her lifestyle was when she was driving to dinner with her mother one night. Her mom told her frankly that it was great she was succeeding at her sport but if she didn’t have a way to celebrate her successes—such as with friends or at a celebratory meal—her successes would mean nothing.

A part of Julie woke up with her mother’s warning.

“I was so pissed. I wanted to slap her in the face because it stung really badly,” Julie said. “I think I realized though that it was sort of true.”

When Julie eventually got to Duke, her disordered eating faded into the background. But after her first year, Julie’s old eating habits remerged in her sophomore year at Duke.

Then one day, after throwing up during practice and having what she describes as a mental breakdown, Julie realized she needed to take a couple weeks off.

“I felt like my mind was in a complete fog, and I just realized I needed to walk away,” Julie said. “If you really love something, I truly believe you have to let it go in order for it to come back to you because if not, it’s an addiction.”

Julie said it felt like a sign when her anemia returned.

“It was kind of something I had to figure out more on my own. It was just kind of coming to realize how much more important our relationships are and life outside of numbers is, which is really hard to navigate when [my sport] is so results-driven,” Julie explained.

Julie said the hardest part of her break was figuring out the source of her pain, which she realized came from some of her relationships, and that adopting poor eating habits was not going to fix these problems.

She has returned to her sport since then, and she believes that her break gave her the necessary time to reflect on her happiness and on her eating habits and reinvigorated her passion for athletics. She also made it a point to reach out to people, telling them how she was feeling and asking for advice.

“I recently had this overwhelming sense that I’m so lucky to be able to find myself at Duke because my personality was so lost for so long in my disordered eating and my habits and outcomes rather than just the process along the way,” Julie said.

Eating disorders in Duke athletics

Both Emily and Julie said that their sports team trains several hours per day and multiple days a week.

“Athletes are going to walk that fine line between healthy training and overtraining to maximize performance,” said McNally, who is currently teaching an “Exercise and Mental Health” course.

Emily mentioned that it is difficult not to count calories when one is on the team, because many of the girls obsessively do so and, as she perceives it, also have poor eating habits. She noted that there is a consistent focus on body image within the team.

“If somebody tells me my abs look great, I'm going to feel good about it, which is a sad thing to say,” Emily shared. “Like with Instagram, I am somebody who is quite obsessed with their body. My [account] used to be a video documentation of my body all the time.”

She said that people often treat athletes like their bodies are completely separate from their brains. Julie worries that this mentality is diminishing her enjoyment of the sport.

“Can I find that love for my sport again, [yet] stripped of this comparison to others, the need to be super thin, to look the way other girls do, to count my calories, to train a certain amount, eat a certain amount?” Julie asked. “I want to love it for what it is.”

The Duke environment

“Many of my patients have told me that their impression is that disordered eating is so prevalent at Duke that it normalizes their own aberrant eating and decreases their motivation to get help,” said Zucker, the founder of the Duke Center for Eating Disorders. “Whether that is the true state of things or just their perceptions, [I don’t know, but] it’s probably a little bit of both.”

Liccione agreed, saying “[Duke] is like the most toxic aspect of United States exercise and diet culture concentrated."

It’s not clear whether or not the Duke environment worsens eating disorders, but Liccione and Zucker suggested students on campus might feel pressured to exercise and eat healthy in order to fit in with their classmates.

Liccione said she often observes which classes tend to fill up the most at the Wilson and Brodie Recreation Centers. From what she’s noticed, the rapid calorie-burning classes such as high-intensity interval training and indoor-cycling get the most packed, but the slower-paced Hatha yoga classes have more empty space.

Liccione frequently took HIIT classes, but she now prefers hatha yoga.

Zucker said students may also feel a sense of competition when they exercise together. If two people are next to each other on treadmills, there’s a possibility they want to outrun each other. Zucker also mentioned that she was alarmed by the number of students who do not allow themselves to take a break from studying during their exercise routines. She often walks through Wilson and notices students with textbooks propped up on their machines.

“It’s sad that we’re so stressed out that we can't even separate our studying from our exercising,” Zucker said.

Liccione also cited Greek life as a potential stressor that intensifies eating disorders at Duke. Although she is not in a sorority, she said she has noticed this among her friends.

“During formal season, it’s very much about appearing appealing—fitting into your formal dress, making sure you’re appearing in-shape for beach week,” Liccione said. “Look at the number of Greek letter-embalmed tank tops in the HIIT classes. You go to the gym, and everybody's got their letters on.”

Emily has seen girls struggle to appear perfect in order to fit in with her sorority. She said they’ve started having chats where everyone shares their feelings. But outside of these chats, when she notices a friend looking upset and checks in with her, the friend brushes her away.

This disturbs Emily, since it was the openness about her eating disorder that allowed her to improve so quickly. When she arrived at Duke, she shared the story of her AN with everybody and people would look aghast and ask her why she was telling them about it, to which she would respond "because it made me who I am.”

She believes part of the problem is that as soon as you join a sorority, you are forced to make several dozen new best friends. You are not going to forge deep connections immediately, so you are less inclined to tell your new sorority sister when you are having a bad morning, she said.

“They're all trying to be as cool as possible,” Emily said.

Liccione said her own eating habits worsened at Duke, not necessarily because of the pressure to exercise or look fit but due to the rhetoric about how busy people are. When her anorexia began to spiral out of control, her schedule was so packed that on Tuesdays and Thursdays she didn’t have time to eat between 7 a.m. and 5 p.m.

Yet, Liccione thought that was normal, because it seemed that everyone around her had just as little free time.

Zucker said that when she learned about the aforementioned ACHA survey, the statistic about loneliness was particularly bothersome. Duke undergraduates reported feeling “very lonely” at a significantly higher rate compared to their national peers. About 60 percent of college students surveyed reported feeling very lonely at least once in the past 12 months, but nearly 80 percent of Duke students surveyed had felt that way.

“It’s the perfect storm,” Zucker said, alluding to Liccione’s point about overcrowded schedules. “It’s very easy for people to get in a rigid routine of studying all the time, exercising very hard, not having a break, falling down the slippery slope of disordered eating pathology.”

Despite its higher rates of exercise and anorexia, Duke has made strides in recent years to combat these problems.

Liccione has noticed a difference in Duke’s approach to mental health, even since she arrived on campus four years ago.

“[Back then], there was next to no mention of dealing with mental illness, CAPS was something that was very ‘hush hush,’ and there was no [National Alliance on Mental Illness] chapter,” Liccione said.

Liccione said one of the aspects of Duke’s approach to mental health which helped her the most during her time off was its commitment to seeing its students through until they graduate.

"One of the things [Dean Sabrina Thomas, director of the Office of Student Returns] does is make a point of saying and acting on this, ‘once you get admitted, we're committed to seeing you through and graduated,'" she said.