Six years ago, William Paul Thomas, the Brock Family Visiting Professor in Studio Arts, was waiting for the bus when a face caught his eye.

“His skin color and the smoothness of his skin, and something about his demeanor really stood out to me,” Thomas said.

Thomas hesitated, unsure whether to approach this total stranger for a photo to capture the moment and to later develop into a painting.

“I didn’t want to bother him,” Thomas said. “I didn’t know if he was tired or on his way home.”

After five to ten minutes of indecision, Thomas finally went for it.

“He lit up,” Thomas said. “He was excited that I had asked him.”

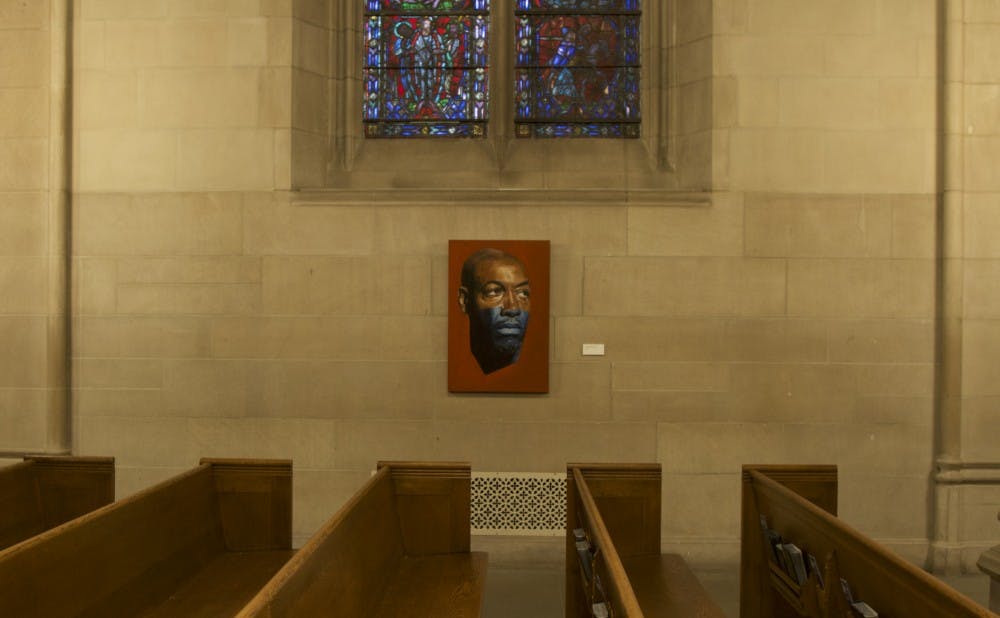

Now, the painting from that encounter acts as the main image in the promotional materials of Thomas’s exhibit titled “Sitters in Transit,” which will line the walls of the Duke Chapel throughout November, bringing pops of color to the otherwise fairly monochromatic space. Each canvas features one or two hovering faces that are partially painted in blues or golds that challenge the naturalistic view of a portrait.

The art exhibits in the Chapel are a part of the larger goals of the Chapel to bridge faith and learning, according to Reverend Joshua Lazard, C. Eric Lincoln Minister for Student Engagement. Since his work focuses on the students, Lazard pays particular attention to their needs in the selection of these exhibits.

Work displayed in the Chapel generally has a component of faith or religion; however, this expression is not always explicit. For instance, in “Sitters in Transit,” some paintings have crosses as part of the composition, while most do not, instead aiming to create a space for reflection on the subject matter. Thomas felt that these works fit into the Chapel space for that reason, as well as the fact that many of the subjects of his portraits are local, representing Duke’s surroundings in a space that Thomas said “embraces community.”

“You might see any one of the subjects come and visit to see the show and stand near their paintings,” Thomas said. “I like the phenomenon of seeing the subject and the painting make an appearance at the Chapel. They’re all people that you could run into or recognize; they’re everyday people.”

Lazard also emphasized the importance of the community in choosing artwork for the Chapel. He tries to ensure that the work will be something that will interest all the various communities that the Duke Chapel serves. Since the establishment of his position in 2014, Lazard has worked to expand and develop initiatives to engage students through the intersection of art and faith, and he plans to continue to broaden those initiatives.

“I see that expansion right here with making sure that we have a robust enough arts program, and for us right now that looks like having exhibitions of artists on the walls here in the Chapel so that the Chapel is a living place, that it lives and breathes to the heartbeat of the community,” Lazard said.

The portraits currently hanging on the Chapel walls depict people Thomas wants to remember — some are family members, friends or other artists, and some are people he has only met a few times. The exhibit title references these meetings that often occurred “in transit,” as well as hints at the wandering of the mind, the reflection Thomas hopes people engage in when viewing his work. As a result of the artwork, Thomas actually reconnected with the stranger who was the subject of the main promotional painting, when another university staff member saw the painting and recognized the subject.

In installing these portraits in the Chapel, Thomas also considered the impact of figurative work, namely whom people see and where they see them. Thomas said racial demographics often stand out to him, and he intends to use installations of his work to examine the representation of people of color in the spaces where he exhibits, as well as to question the expectations placed on black artists. Thomas works to focus on the mundane aspects of human existence, rather than the large injustices or discriminations — while those topics are important, he felt that they fail to reflect the true day-to-day experience that he tries to capture.

“My friend told me that I was a phenomenologist, and I like that label,” Thomas said. “A lot of times I’m responding to phenomena, my experiences and observations, without necessarily putting a cap on what I’m able to explore.”

Thomas uses his art to examine his personal narrative as well. While he has loved drawing for as long as he can remember, he started to see the possibilities for a career in art only after he had started his undergraduate education.

One particular series, called “Hot Pink Brick,” drew on Thomas’s past. It consists of a variety of images featuring a bright pink painted cinder block, reminiscent of the color his mother painted on the walls of his childhood subsidized housing unit in Chicago’s Altgeld Gardens.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Thomas vividly recalls an image of himself and his two sisters, dressed in Catholic school uniforms of maroon and gray, set against the bright pink wall.

When he first shared the project online, Thomas did not tell people about the brick’s particular significance to him. Instead, he left it abstract, open to interpretation, and invited people to make and share their own images with a bright pink cinder block.

“It’s a reminder to me of all of our different paths — where we’ve been, where we end up, where we’re going, and you never know how intricate someone’s life story is, what are the small patterns or objects that remind us of home,” Thomas said. “Now I can’t look at any cinder blocks without thinking about that home, that childhood experience.”

Correction: A previous version of the article misspelled Altgeld Gardens. The article has also been updated to reflect that Thomas met the subject of his painting while waiting for the bus, not while on the bus. The Chronicle regrets the error.