Duke faculty have come closer to pinpointing how their poliovirus treatment for glioblastoma works, opening up new avenues for treatment across different cancers.

With a 20 percent three-year survival rate in patients, the poliovirus treatment has gained widespread notoriety for its position as one of the few promising options for glioblastoma. The Duke team behind the poliovirus is currently gearing up for more clinical trials to test the therapy on the heels of receiving "breakthrough" designation by the Food and Drug Administration. Using their latest findings, researchers may now have a better understanding of what existing therapies might be combined with the poliovirus treatment for maximum efficacy.

"We have shown that oncolytic poliovirus can make a ‘cold’ tumor—with no immune response—‘hot’ in mouse tumor models," said Smita Nair, professor of surgery. "This opens up new, exciting avenues for testing oncolytic poliovirus in combination with immune checkpoint blockade, including in patients who do not respond to [just] immune checkpoint blockade.”

Noble beginnings

In 1994, Matthias Gromeier, professor of neurosurgery, first modified the poliovirus, swapping part of its genetic code with that of a common human cold virus. This engineered hybrid, called PVSRIPO, was designed such that it could not cause polio in humans.

Six years later, Gromeier shared his discovery that the virus locks onto brain tumor cells which are subsequently destroyed by the body's immune system, raising the exciting possibility of its use for brain cancer treatment.

The vision he and the rest of Duke's Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center shared has come to life in the years since, with initial data on treatment success first reported in 2015.

In 2016, the FDA granted “breakthrough status” to Duke’s poliovirus therapy, facilitating the remaining process toward approval for treatment of glioblastoma.

Nevertheless, Nair said this does not guarantee that the FDA will approve the poliovirus therapy and that years of research remain. The researchers wish to continue improving the virus as well as conduct more lab research regarding treatment of other common cancers.

For eventual clinical trials of other cancers, the researchers are exercising caution, making sure they are truly ready before they move forward.

From here, the Duke researchers will continue to explore ways to combine poliovirus therapy with other cancer drugs for increased effectiveness.

How it works

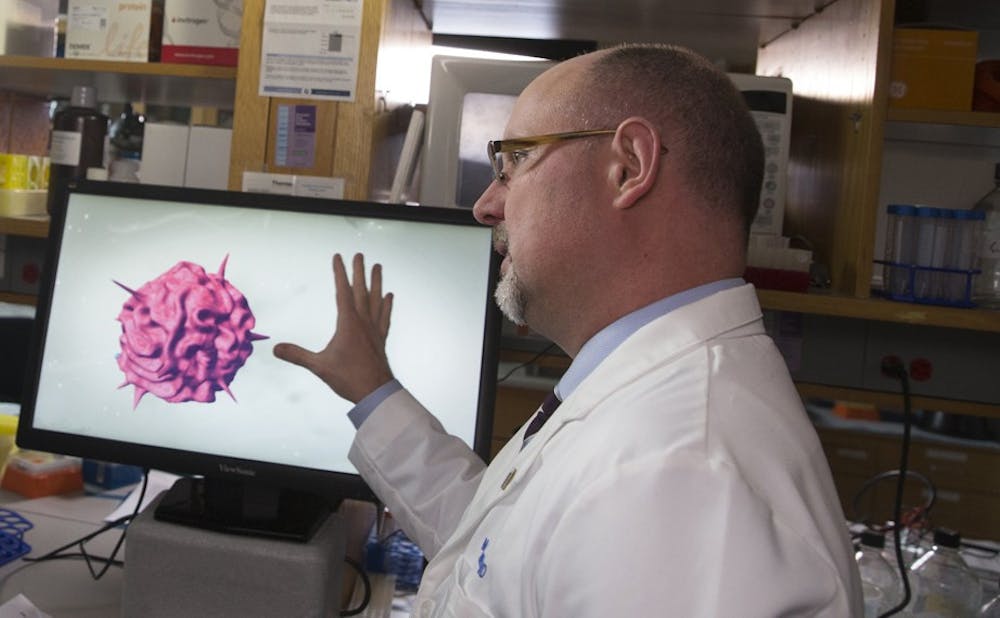

Cancer cells in a tumor are typically well-adapted to avoid detection and interference from the immune system. To circumvent this limitation, the group injects the poliovirus at the tumor site to elicit a one-two punch against the cancer, Nair explained.

With the first punch, the virus links up with a protein known as CD155, which is found abundantly on the cancer cell’s surface. It next replicates inside the cell, creating copies of itself that then destroy the cell as they break out looking for other cells to infect. This death-by-virus aspect of the therapy kills many tumor cells directly.

As the viruses emerge, they break the cell open, spilling proteins and other cell ‘guts’ that alert the immune system to the cancer’s presence, prompting immune cells to go on the attack. This initiates the second punch of the therapy’s attack.

“Not only is poliovirus killing tumor cells, it also infects the antigen-presenting cells, which enables them to raise a T-cell response that can recognize and infiltrate a tumor,” Nair said.

Cancers have the ability to mask themselves and lie low under the immune system’s radar. Cancers can lose their advantage, however, when their presence is flagged using the poliovirus. By enlisting the help of the immune system, the poliovirus therapy ensures anti-cancer effects will last longer.

The results of their latest research also suggest that this treatment could work well with other types of immunotherapies. The team will soon begin oncolytic poliovirus testing in pilot studies with breast cancer and melanoma patients.

Correction: This article was updated on Oct. 22 to note that Nair is a professor of surgery, not an associate professor of surgery.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.