When David Steinbrenner was growing up in Mesa, Arizona, houses with front porches were a luxury. So when he purchased his first house—a brand-new, three-bedroom property in Durham’s newly-revitalized Southside neighborhood—its sweeping front porch excited him most. Hailing from a relatively modest background, he never imagined that he would own his dream home by age 40.

In 2014, Steinbrenner bought this home with the help of Duke's affordable housing initiative for low-income university employees to purchase property in Southside. The initiative was founded in 2012 by Duke as well as the city of Durham, Self-Help Credit Union and other nonprofit developers to help the area flourish. As a staff assistant in the Office of Postdoctoral Services, Steinbrenner qualified for the University's aid.

Yet less than four years later, Steinbrenner now lives in a neighborhood that exemplifies the rampant gentrification that has displaced so many low-income residents from areas in downtown Durham.

“It’s sort of this weird tension because I’m both grateful for the opportunity, but there’s a bit of guilt when you start thinking about the folks who might not be able to live in their own neighborhoods," he said.

Duke’s investment in Southside

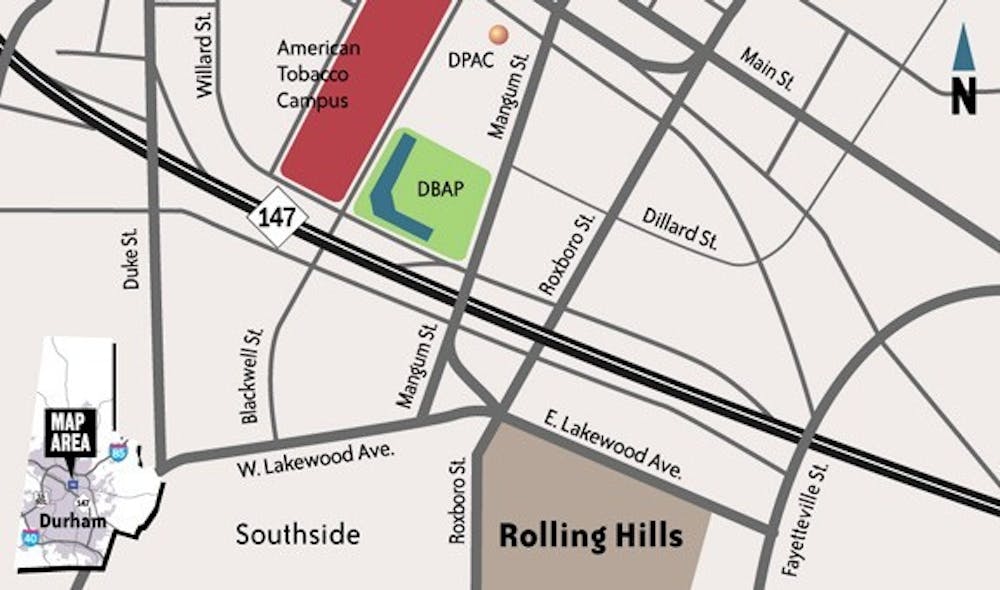

The Southside revitalization project involved the redevelopment of Southside and an adjacent 20-acre site called Rolling Hills. Southside itself is located south of the Durham Freeway and north of the North Carolina Central University, near the American Tobacco Campus.

Both sites are situated in the Hayti district, Durham’s historically black neighborhood that was largely demolished in the 1960s by the construction of the freeway.

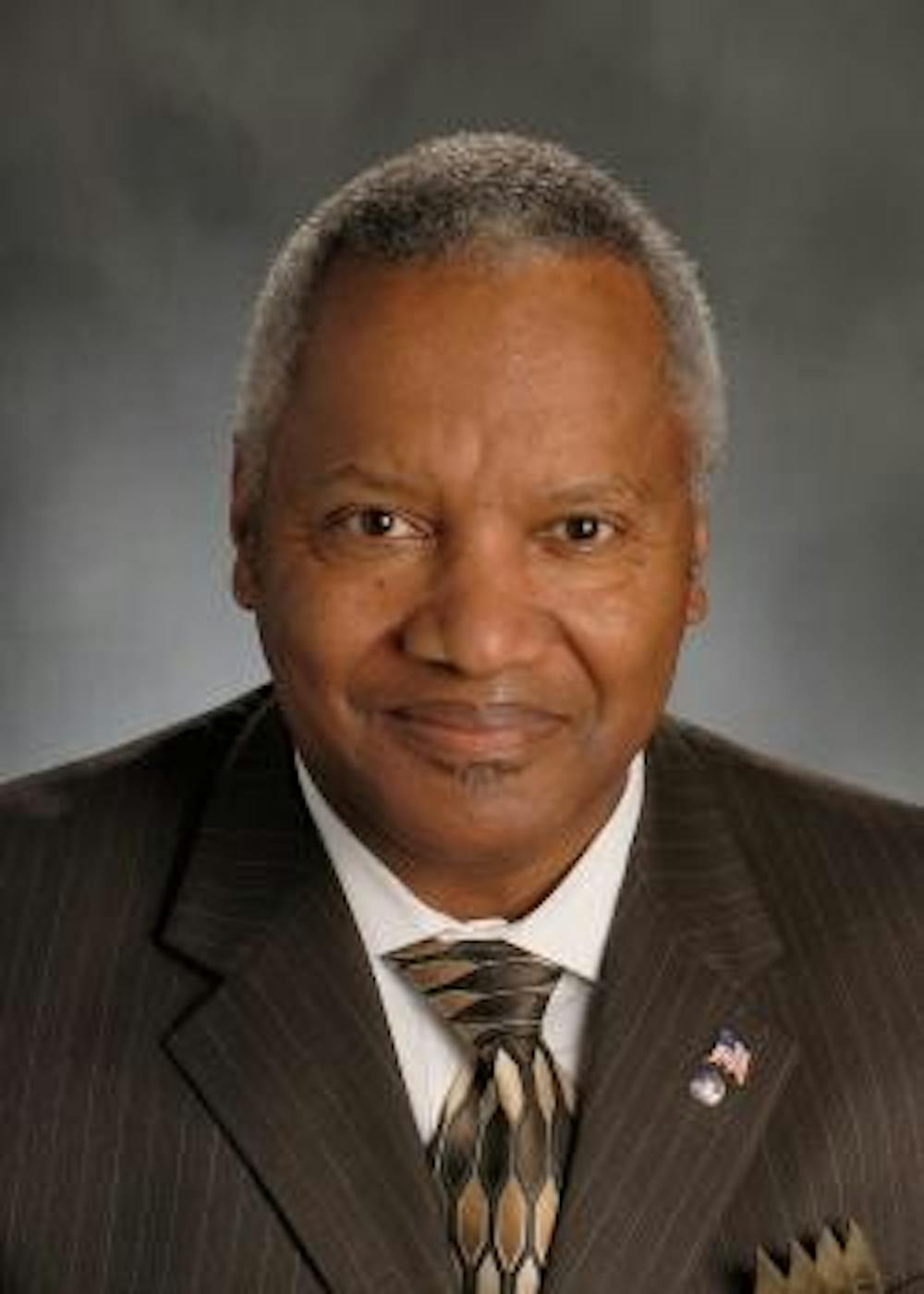

In 2008, shortly after he began working at Duke, Phail Wynn Jr.—vice president of the Office of Durham and Regional Affairs—went with Durham city manager Tom Bonfield and Evan Covington Chavez, director of real estate at Self-Help Credit Union at the time, to visit Southside. Back then, the neighborhood was mostly abandoned with dilapidated homes and high rates of violent crime.

“It was a haven for drug sales,” Wynn said. “Gangs had taken over that territory, and it was largely abandoned and devastated. It was unkempt with a lot of vacant houses. It was an eyesore.”

The three of them decided to create a partnership between the city, Duke and Self-Help to revitalize Southside. Collaboration between Duke and Self-Help was nothing new—they have partnered since 1994 to re-develop Durham neighborhoods, as well as to build and sell affordable homes.

Reginald Johnson, director of Durham’s Community Development Department, said that in 2008 Southside had very few investors and even fewer homeowners.

“You couldn’t get a builder to go into that neighborhood because you couldn’t sell the house for more than it cost to build it,” he said. “Our goal was to use our public dollars to engage the community.”

Duke’s involvement in the revitalization project included two components—a loan commitment and an affordable housing initiative. The project was designed to create an affordable community through rental and homeownership opportunities, as well as to renovate the houses of existing Southside residents.

In 2011, Duke doubled its loan commitment to Self-Help Credit Union to $8 million, with the Southside revitalization earmarked as its priority.

Self-Help used the money to purchase properties and land in Southside for redevelopment. With the help of the city and low-income housing tax credits, the first phase of the revitalization project built 48 houses, Johnson said. About 26 of them were reserved for purchase by low to moderate income residents. All 48 homes had been bought and occupied by 2017.

“In this particular project, Duke has been very important,” Johnson said. “Self-Help could not have done the work they did without the help of Duke.”

Affordable housing initiative

Duke also offered an affordable housing initiative for low to middle income employees to buy houses in Southside, including a forgivable mortgage loan program of $10,000. Eligible employees needed to have worked for the University for more than five years and earn $40,000 or less annually from Duke and have less than $66,000 in total income if part of a two-person household. The city also offered attractive loans and incentives for low and moderate income buyers.

Steinbrenner was the first resident of one of the new houses. He qualified for Duke’s forgivable loan program and used it as a down payment for the house.

“Without the funding that Duke gave me, it would have been near impossible to buy the house,” Steinbrenner said.

But although the forgivable loan program initially aimed to select 10 employees, only three were given loans.

Wynn said the program received more than 100 applications from eligible Duke employees but most did not have the credit scores or liquid savings to qualify for a first-home mortgage.

He explained that this meant employees who were on the lower end of the income scale were less likely to be approved for the mortgages and receive forgivable loans.

Steinbrenner agreed with Wynn's sentiment that the forgivable loan program seemed to accommodate a specific demographic.

“What ends up happening though is that with people like me, you end up with a bunch of white, graduated or educated people who don’t maybe have high income yet,” Steinbrenner said. “So in terms of getting a really diverse socioeconomic or racially diverse mix into the houses, it ended up being—while not entirely white—pretty darn white.”

Gentrification concerns

As affordable housing becomes increasingly scarce in Durham, Southside's gentrification has raised questions about Duke's partnership with the city and Self-Help Credit Union as well as the group's ability to help low-income individuals find economical housing.

Houses in the revitalization project were priced in the range of $162,000 to $198,000, based on their size and design. Three years later, houses are being listed upwards of $300,000.

“The price on [my] house was actually reasonable,” Steinbrenner said. “Now, there’s no way that we could get a house in the neighborhood for what we paid.”

He noted that his main concern is for the low-income renters in old houses because as prices rise, they are more likely to get pushed out

“That’s really the dark side of the whole thing. Gentrification is not a myth—it’s really happening,” he said.

James Eller, who has lived on South Street in Southside since 1958, said the extensive development following the revitalization project has made his future in the neighborhood uncertain. Up and down Eller’s street, old houses are being torn down as new, expensive houses are built in surrounding lots.

“I feel like it’s just a matter of time before someone from the city comes to tell me that I’ve got to move or get my house up to code,” Eller said. “And I don’t have the money to fix it.”

Eller said that prior to the revitalization project, there had been no interest in enforcing the code. Although the project has improved city services in Southside and created new features like street lamps and freshly painted crosswalk lines, this stands in stark contrast to the lack of commitment when Southside was a mostly black neighborhood.

“Basically, this part of South Street, everybody is white,” Eller said. “It’s a shame that in the 50s they didn’t want to be around us. Now, all of a sudden they want to be around us. They want to be in our neighborhoods. I wish they felt the same way back then because I’m sure this would be a better place to be [if that had been the case].”

Higher property valuations as a result of the revitalization have led to increases in property taxes. The city council recently approved a proposal to provide grants for longtime residents struggling to pay higher property tax bills.

Still, Eller said he may have to sell his family home.

“The houses are so priced out here that we can’t afford them,” he said. “When people have power over you, they can do tricky stuff to get what you got and you can’t do nothing about it.”

At a Durham mayoral forum in September, some candidates said the Southside revitalization project was an example of unsuccessful affordable housing.

Mayoral candidate Sylvester Williams said the city’s investment in Southside showed that it was primarily concerned with the economic growth of the downtown area, at the expense of other low-income places. He noted that low-income residents do not have a place in the city.

“Is everyone being negatively affected equally?” Williams asked. “We’ve not seen a level playing field when it comes to people of color or people of lower income.”

Former city councilwoman Jacqueline Wagstaff, who also attended the forum, said that Duke led the Southside redevelopment because of its proximity to downtown and in order to benefit higher-income employees.

“There’s no poor people who can afford to live there anymore,” she said. “There is a whole initiative to have this kind of joyland in and around the [Durham Bulls Athletic Park]. They want to live, play and have a good time all around that ballpark, and Southside is within walking distance of that.”

Although the Southside initiative was successful at first in improving the neighborhood and generating wealth, the project's shortcomings demonstrate the challenges of creating effective affordable housing strategies, Wynn noted.

“Southside is an affordable housing planned complex that is rapidly becoming unaffordable,” he said. “But it showed the effectiveness and the power of a strong partnership between a private university, a city government and a community-based bank. This is something we can replicate with the lessons learned from this project.”

He said that Duke remains committed to the affordable housing issue and to being a responsible neighbor in Durham.

The Duke Homebuyers Club—which is run by the Office of Durham and Regional Affairs and helps employees repair their credit scores and increase their savings through an eight-week program—was created in response to the issues encountered by the Southside affordable housing initiative. More than 20 employees have been approved for first-home mortgages after going through the program.

As for new affordable housing investments in Durham's neighborhoods, Wynn said Duke will approach them with caution.

“Until we figure out how we can prevent our next project from becoming gentrified, we won’t do the next project,” Wynn said. “The first step is to figure out—so how do we prevent a reoccurrence of what happened at Southside?”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.