Three months before Mike Krzyzewski won his first national championship in 1991, Duke lost to Virginia in a lackluster game on the road.

Krzyzewski probably could have tolerated a close, hard-fought loss against a strong opponent, but not a defeat like this, a blowout at the hands of inferior competition.

“We really didn’t play well at all,” point guard Bobby Hurley said. “It was one of our poorest games.”

The Blue Devils were ready to put the loss behind them when they boarded the bus in Charlottesville that afternoon, ready for the three-hour ride back to campus and quietly planning their last Saturday night of winter break. But Krzyzewski was not about to let them forget the lousy performance so easily.

The bus arrived at Cameron Indoor Stadium at about 8:30 that night, Hurley remembers, and Krzyzewski got up from his seat at the front to address the team, presumably to tell them what time practice would be the next day.

“Get taped,” Krzyzewski growled instead. “And get on the floor in 20 minutes.”

It didn’t matter that the team was tired from a physical ACC basketball game and stiff from a three-hour bus ride. They would play for two more hours at home in Cameron against each other, and they would get it right this time.

Hurley remembers sprints up and down the floor, battles for loose balls, elbows flying. Star freshman Grant Hill broke his nose in the practice and had to miss two games.

Shortly thereafter, the NCAA passed a rule restricting practices on the same day as games to protect its treasured student-athletes, but the message had been sent. Duke lost four more games that year, but never in such embarrassing fashion, and never when it mattered most in the NCAA tournament.

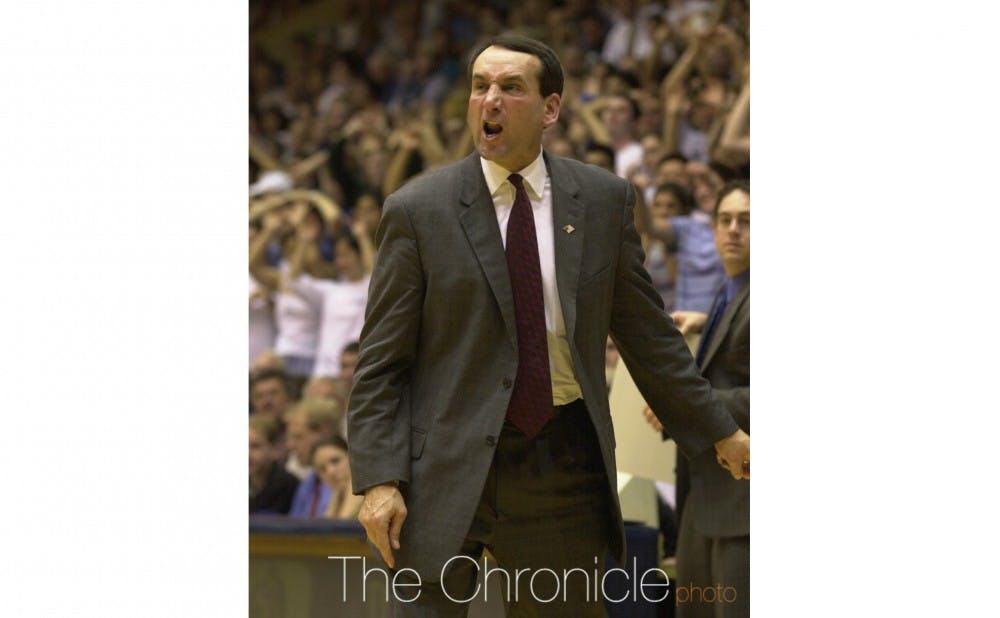

FEARING THE SNARL

It starts with a piercing stare, as Krzyzewski pauses for a beat while contemplating which four-letter word to use to start his tirade.

His dark eyebrows shoot up into arches, revealing a few wrinkles on his forehead. His eyes narrow, the white around his brown irises temporarily vanishing while an unfortunate player looks into a dark pit of fury.

“You never wanted to let him down,” Hurley said.

His upper lip curls into a snarl, his lower lip starting to move while words come flowing out with a cadence that has taken a lifetime of practice for the West Point-educated disciplinarian.

His neatly trimmed jet-black hair stays intact. A tuft curves over the top of his head, combed to the left and never covering much of his forehead. Three years ago, Krzyzewski denied dyeing his hair in response to an inquiry from News & Observer reporter Laura Keeley. Living to 70 without a single gray strand emerging would be a remarkable achievement if he was telling the truth.

But at age 70, as the third-oldest Division I head coach, Krzyzewski still reaches players more than 50 years younger than him. By using everything from rap music to ice cream, interviews with Krzyzewski and more than 10 former players showed he still finds unique ways to connect with his teams.

He inspires in different ways. Sometimes he yells and curses and puts his team through hellish workouts. Other times, he uses trickery before serving sweets. And throughout it all, he shows loyalty and love to players and their families.

‘YOU WERE DEPLORABLE’

Trajan Langdon was the target of the snarl in 1996 for a game that didn’t even matter.

Langdon had missed the previous season with a knee injury and was easing his way back into action during the Blue Devils’ exhibition games. His first real test was a game against the Melbourne Tigers—an Australian professional team—before the season started. The Tigers were led by 6-foot-7 guard Andrew Gaze, three inches taller than Langdon and 11 years older. In Gaze’s college days with Seton Hall eight years earlier, he had terrorized Duke in the Final Four.

As expected, Langdon was no match for the best player in Australia, who scored 39 points in the game.

“He kicked my ass,” Langdon said.

The Blue Devils still managed to beat the Tigers 80-69, but Krzyzewski didn’t seem to care about the win in the locker room afterward.

“I was the first person he went at right after the game,” Langdon said. “I’m 20 years old, and he said, ‘Trajan, you were deplorable tonight. You’ve been starting, but you’re not starting anymore. You have to earn this.’

“I had to go home and look up the word deplorable.”

It didn’t take long for Langdon to get the message. He earned his starting spot back by the beginning of the regular season and was a first-team All-ACC selection in each of his last three years. As a senior in 1999, Langdon led Duke to a 37-2 season and a return to the Final Four.

“Direct confrontation is the truth,” Krzyzewski said. “I want them to know that I’m the one person in their life—and their parents might do it, but I might even do it quicker—I’m going to tell you truth at a moment’s notice.... You should want me to tell you that, and that’s when the relationship goes, ‘I got you Coach. You’re right.’”

WHAT’S HE GOING TO DO?

Hundreds of Blue Devils have played under Krzyzewski over the years, sitting through profane tirades in practices and huddles or listening to their coach crack jokes with his sarcastic wit, with both sometimes occurring in the same hour. Former players say Krzyzewski manages to feel the pulse of each individual player and team, finding what motivates them and adapting every year to a new generation.

That has become more challenging in the last decade, though, due to an infusion of one-and-dones. The NBA instituted a rule in 2006 that made players ineligible for the league until a full year after they graduated from high school, resulting in a new crop of players every year that serve as short-term rentals for powerhouse teams like Duke and Kentucky.

“Because of all the peer pressure involved nowadays with kids who are very good players, if you become a senior, you’re somehow a failure,” said John Feinstein, an author who has covered Krzyzewski since the coach arrived at Duke in 1980. “That is the biggest adjustment that all coaches have had to make.”

Krzyzewski was hesitant to recruit players who had no intention of spending more than one year in college until the last decade, and since 2011, 10 one-and-done players have made pit stops at Duke. He won a national championship with three freshmen starters in 2015, and he has the No. 2 recruiting class in the nation lined up for next season.

“He said to me once, ‘If I don’t recruit these guys to play for me, someone else is going to recruit them to play against me,’” Feinstein said.

As Krzyzewski is getting older, his teams are getting younger. He now has to motivate and rely on 18-year-olds instead of 21-year-olds, all while his age is starting to take its toll. In early January, he had surgery to remove a fragment of a herniated disk in his lower back and took a month-long leave of absence in the middle of the season for the first time since 1995.

Krzyzewski no longer has an endless supply of energy for fire-and-brimstone tirades to spark his team and has found that yelling is not always effective with today’s players, either. He leaves it to his younger assistants and team leaders to bring the energy, and where he reacted to Langdon’s missteps with fierce competitiveness 20 years ago, he might use a similar situation as a calmer teaching moment with his current teams.

“Doing it that way now wouldn’t be as good as what I’m doing right now,” Krzyzewski said. “People say, ‘Man, you’ve changed.’ Of course we should change.”

Most of Krzyzewski’s peers, rivals and mentors retired younger than he is now. North Carolina’s Dean Smith abruptly stepped down at age 66 in 1997, and Bobby Knight retired at Texas Tech in the middle of the 2008 season at 68.

Krzyzewski has outlasted all of them and is now the third-oldest of the 351 Division I head coaches, with five years at Army and 37 at Duke under his belt.

“He doesn’t play golf,” Feinstein said. “If he stops coaching—when he stops coaching—what’s he going to do?”

Even as the college basketball landscape has changed, Krzyzewski’s players say the same thing attracted them to Duke—his honesty.

If other coaches can even get inside the home of a McDonald’s All-American, the coach may promise free reign on the court and an immediate opportunity to showcase their skills to NBA executives as soon as they wish. Not Krzyzewski.

“He didn’t promise me a place in the starting lineup, and he didn’t dangle before me the potential spoils of victory,” former National Player of the Year Shane Battier wrote in a blog post about Krzyzewski in March. “Instead, he promised me only one thing: That every day I would have the opportunity to earn playing time.”

That common thread has kept practices intense for the last 37 years regardless of how many high-school awards and accolades players carry with them onto the court for the first time.

“We’re not taking away the single most fundamental thing for you to get better—hunger,” Krzyzewski said. “If you’re promised, hunger might wane.”

Most of Krzyzewski’s recruits in his first three decades waited their turn, learning from junior and senior captains who spent most of the time on the court. None of Krzyzewski’s players left even a year early for the NBA until 1999, his 19th year at Duke.

“There was just this long line of guys coming in when a guy was going to be graduating, and you’d get a year under a really good experienced senior,” said Cherokee Parks, who was Christian Laettner’s seldom-used understudy as a freshman in 1991-92 before leading the team in scoring three years later. “You had time to bring a guy in and have them develop as a guy was moving out.”

At the heart of this mentality is Krzyzewski’s fist philosophy, with the Blue Devil coach encouraging his players to use the fist bump to encourage each other instead of the more mainstream high five. Former NBA guard Fred Carter, who played in the 1970s, is known as the father of the fist bump, but Krzyzewski’s teams popularized it in the next few decades as a metaphor to show no individual is above the team.

Krzyzewski has even named the five fingers when he makes corporate speeches in the offseason to apply to other fields—communication, trust, care, collective responsibility and pride. The fist philosophy has become his version of John Wooden’s Pyramid of Success, a blueprint for excellence on and off the court.

“They’ve got it everywhere now. They’ve got it on shirts,” Parks said. “That was seeded in his early years. You’ve seen what it’s grown into now, but that was seeded with the teams in the ‘80s and when I got there in the ‘90s.”

Green lights may not be promised, but they can be earned.

Chris Collins took his seat in Krzyzewski’s office in 1996 with his senior season on the brink of unraveling. The Blue Devils were floundering in ACC play with four losses in a six-game span and appeared to be on their way to missing the NCAA tournament for the second straight year.

Krzyzewski prepared an individual film session for Collins—the team’s best player and only senior—the day before the next game against Virginia, but reconsidered and turned it off after watching one play. Krzyzewski is a master tactician, but this was not a time for a technical talk filled with X’s and O’s.

“I want you to go out the last month of the season and I want you to play as if you can do no wrong,” Collins remembers Krzyzewski saying. “You can shoot whenever you want to shoot. I’m only going to take you out of the game if you ask for a sub.”

There would be no snarl waiting on the sideline after every bad decision. Collins had been given a free pass to play with no pressure and no consequences for the rest of his career.

The tactic worked. Collins scored more than 20 points in four of the next five games, and the team won four of those five games to solidify a place in the NCAA tournament. The season was derailed in March when Collins broke his foot in the last game of the regular season against North Carolina, and Duke lost in the first round of the postseason, but Collins’ meeting with Krzyzewski was still enough to extend the season by a week.

Krzyzewski, Collins said, “made me feel like a million bucks knowing that he had my back.”

‘WHEN TO DIAL IT BACK’

Former walk-on Andy Borman—Krzyzewski’s nephew—doesn’t remember who Duke lost to in 2002, but he does remember the sinking feeling in his stomach when he and the Blue Devils arrived at practice the next day. Krzyzewski was nowhere to be found when they walked onto the floor, but he had left his assistants to do the dirty work.

Johnny Dawkins, Steve Wojciechowski and Collins—who returned to join the staff in 2000—immediately turned the players away. The team was sent back to the locker room, told to change out of their practice gear—that seems to be an almost annual form of discipline from Krzyzewski—and put on their running shoes instead of basketball shoes.

“Guys, today’s going to be a nightmare,” Borman recalls the coaches telling them.

When they emerged from the locker room, it appeared that the coaches weren’t kidding.

“I’m not joking, there had to be 150 cones on the floor,” Borman said. “We’re looking at these cones going ‘Good God, how much are we going to run today?’”

At this point, Krzyzewski strolled into Cameron to face his team. To his players’ surprise, he was not angry.

“All the guys expected that to be one of those days where you come in and we just beat them down,” said Collins, now the head coach at Northwestern. “His instincts told him this team doesn’t need that kind of coaching right now. They need some joy. The air needs to be let out of the balloon a little bit.”

The cones were all a ploy. There would be no tiring conditioning workout and agility exercises, just games of dodgeball, capture the flag and relay races.

After losing a game as the defending national champions and the top-ranked team in the nation, playing for Duke was suddenly fun again.

“There’s an inordinate amount of pressure when you’re a Duke basketball player,” Borman said. “To be able to make the practice and make the game fun—his timing is just incredible, when to dial it up and when to dial it back.”

It was not the first time Krzyzewski has toyed with his teams’ emotions. During the 1992 season, another year following a championship, he had the team meet at Wallace Wade Stadium the day after a loss to Wake Forest, where the Blue Devils were expecting to run up and down the steps of the football stadium for the entire practice.

Instead, he gave the team a quick complimentary talk before sending them back to Cameron, where they had cake and ice cream in the film room. The team never had to break a sweat.

“You kind of brace yourself for those days when you know they’re coming, and then it was a complete opposite with the ice cream,” said Hurley, now the head coach at Arizona State. “I remember being surprised that that’s the approach he took, but that’s another way a coach is able to get through to you, by going a different way and always keeping you off-balanced.”

The team loosened up and did not lose again the rest of the season on its way to a second straight national championship.

“You try to make a read. One of the main things you look at is, ‘Are they playing their butts off?’ If they’re playing their butts off, I’m always positive. Always,” Krzyzewski said. “You’ve got to be close enough to your team to read their facial expressions, their body language, how they are talking to one another. In other words, watch human beings.”

‘A TEXTING MADMAN’

In this year’s NCAA tournament, celebrating coaches on winning teams were often seen prancing into the locker room and getting soaked by water bottles or doing handstands in front of their teams. Krzyzewski was never one of them, and not just because he is physically incapable of doing anything close to a handstand after undergoing five surgeries in the last year—the back surgery, a knee replacement, two ankle procedures and a hernia surgery.

“He’s always genuine,” Borman said. “A lot of coaches, the way that they try to relate is by bringing themselves down to the age and the immaturity of the kids they’re coaching, and they kind of give off the impression of being buffoons.”

But Krzyzewski still finds a way to reach this generation. The New York Times reported in March that he made his own Bitmoji, a cartoon avatar that resembles him and is captioned by an inspirational saying. Krzyzewski’s has the caption, “You can do it!”

Those popular ESPN commercials on an endless loop last summer that showed his grandsons translating texts he dictated to players into emojis? They might have been a little misleading—he can text players just fine by himself.

“He’s a texting madman,” Feinstein said. “He texts everybody all the time. Those are things that you never would have thought him capable of as recently as five or six years ago.”

Krzyzewski monitors his players on Twitter and Instagram although he does not have public social media accounts, and his interest in modern culture extends beyond technology and social media. He even admitted at the championship celebration two years ago he is a fan of the rapper Meek Mill.

Although Krzyzewski has a comfortable office on the top floor of the Schwartz-Butters Athletic Center next to Cameron, overlooking Krzyzewskiville—the patch of grass that becomes a tent city of students every winter—he spends more of his time in a separate office tucked away next to his team’s locker room inside the depths of Cameron.

From there, he can listen in on his team and absorb the culture of a group two generations younger than him.

“It’s like a garage office, but it’s locker-room level,” Krzyzewski said. “I hear the music. I like the music. I’ve stayed current. Obviously, I can’t stay current with all the styles because I’d look like an idiot, but some of it I do.”

Krzyzewski and his staff put together highlight videos to pump their team up at a meeting the night before many games, and on April 5, 2015, the night before the Blue Devils beat Wisconsin in the national championship, the soundtrack was Meek Mill’s “Dreams & Nightmares.”

The song is more profane than a Krzyzewski rant—quite an impressive feat—but the inspirational message shines through in snippets.

“It was time to marry the game and I said, ‘Yeah, I do’

If you want it you gotta see it with a clear-eyed view.”

Krzyzewski became the second-oldest man ever to coach a team to a national title the next day.

And although he has learned to adopt rap and hip hop, his true musical preferences lie with another contemporary artist.

“If you like Beyonce, he’ll be right there with you,” said Andre Dawkins, who played for Krzyzewski from 2009-2014. “One time, he showed us a clip of her singing. I think it was from Dream Girls.”

On a winter day before ACC play started one year, Dawkins remembered Krzyzewski leading his players into Cameron, asking them to look up at the banners in the rafters.

The stadium was empty. Just ahead of them were four big national championship banners behind one basket, flanked by 15 Final Four banners and more ACC tournament banners down the sidelines.

There also were the 13 retired jerseys, remnants of an era of Duke history that has passed. The Blue Devils have not retired a player’s jersey in the last decade, and it is hard to see them doing so again, since few of their best players stay for four years anymore and Krzyzewski requires that a player graduate before his number rises to the rafters.

Every banner during Krzyzewski’s tenure represents a meaningful accomplishment, a time when he has shed his snarl in favor of a smile. When Duke earned its next banner a couple years later, advancing to the 2015 Final Four on the way to Krzyzewski's fifth national title, his eyes watered as he bear hugged his captain Quinn Cook. His cheeks reddened with joy, flushed outward instead of sharply inward.

This version of Coach K does not emerge in public often, but the desire to see it has helped generations of Blue Devils play with more hunger every year.

5,000 MILES

Krzyzewski will take his team a long way to show his fondness for his players, even all the way to Alaska.

When Krzyzewski recruits players from a region Duke doesn’t usually visit as part of its regular ACC schedule, he usually tries to plan a nonconference game in their hometown as a token of appreciation.

Duke has played on every coast and even in Hawaii five times for the early-season Maui Invitational, but when Langdon arrived in 1994, it had never ventured north of New England. Once Krzyzewski signed the star guard, though, he entered Duke into the Great Alaska Shootout—an early-season tournament hosted by Alaska-Anchorage—in the 1995-96 season.

The Blue Devils won the tournament and the trip would have been checked off the to-do list, except for one problem—Langdon couldn’t play. He was injured that season, so all his family could do in their shortest trip ever to see him was watch him sit on the bench.

Unbeknownst to Langdon, Alaska would get another chance. Krzyzewski immediately started preparing to go back to the tournament three years later, when Langdon was a fifth-year senior captain.

“It’s something that has to be done a couple years in advance, so he must have done it at some point during my redshirt sophomore year,” said Langdon, now the assistant general manager of the Brooklyn Nets. “That was incredibly special that he thought about that.”

Krzyzewski doesn’t just love his stars.

Ricky Price began his career with great promise when he arrived at Duke in 1994 and peaked as a sophomore, starting almost every game and being named the team’s defensive player of the year at the postseason banquet. But his career fizzled from there.

An academic suspension for plagiarism kept him off the court for the fall of his senior year, and Krzyzewski kept him on the bench most of the time even when he returned to the team. Price acknowledged he and his head coach “weren’t on great terms” at the end of his senior year before a productive one-on-one meeting that Krzyzewski has with all his players after the season ended.

“We had a big powwow where we were able to iron some things out,” Price said.

Price faded into obscurity after spending his last two years on the end of the bench, disregarded by most of the public. He is the kind of guy a Hall of Fame coach could easily forget.

But Price and Krzyzewski stayed in touch, and it paid off more than 10 years after Price graduated, when he broke his tibia and fibula playing pickup basketball in his hometown of Charlotte on his birthday.

“I called Gerry [Brown], his personal secretary who handles his ticket requests and everything, and she let Coach know that happened,” Price said. “He called immediately and set up an appointment for me to come to Duke and have my surgery.... He didn’t have to do that.”

After Price’s surgery on his broken leg, Krzyzewski checked in on him in the hospital and called to make sure he settled back into Charlotte after he was discharged.

Price remains grateful for Krzyzewski’s care during that time and still talks with him every few months, about his family, about his basketball clinics—he coaches teens through the company he founded, Game Ready Skills and Development—about anything.

“Ricky went through a couple really tough things here as a player, and he didn’t really understand everything as well at that time in his life as he did later,” Krzyzewski said. “I admire the fact that he got it.”

Price was one of about 30 former and current players in Durham this weekend to help coach at the K Academy fantasy camp, an annual example of how many players Krzyzewski still keeps up with regularly. With Krzyzewski sitting in his meeting room, the sound of new basketball shoes squeaking on the floor is audible through the hallway, as middle-aged men live out their dreams in front of Blue Devil legends spanning Krzyzewski’s career. Their former coach and lifelong friend is the one thing that links them together.

As Krzyzewski put it, “It’s like having this incredibly large family.”