How important do Duke professors consider their teaching responsibilities? During summer break when many get a respite from instructing undergraduates, professors reflected on how they balance teaching with other obligations.

A faculty member's job is divided into three parts—teaching undergraduates, conducting research and serving the University, through activities such as managing a department or sitting on a committee.

Although young faculty members are often hired for their research proficiency and then quickly begin serving on University committees, learning how to effectively teach often comes more slowly. Several faculty members addressed how they have been able to balance these three obligations and hone their teaching skills along the way.

Learning to teach

Patrick Charbonneau, associate professor of chemistry, described teaching as a multifaceted task that requires many different skills.

“[Teaching] means being at the front of a classroom and telling a compelling story,” he said.

But incoming faculty may not be prepared to do this when they first arrive at Duke.

Kenneth Glander, professor with tenure of evolutionary anthropology who has retired from teaching, explained that when Duke offered him a job after graduate school, he had not yet learned how to become an effective instructor.

Susan Alberts, Robert F. Durden professor of biology and anthropology, noted that there could be more instruction in teaching for faculty.

“Duke doesn’t explicitly train new faculty how to teach,” she said.

Although Duke will sometimes try to help faculty improve their skills in the classroom, there is no mandatory course or mentorship centered around teaching, said Owen Astrachan, professor of computer science.

One department facilitates a program to help provide a higher quality of teaching.

Edmund Malesky, professor of political science, explained that the political science department administers a certificate program for graduate students on teaching politics.

He noted that graduate student teaching evaluations factor into the department's recruiting process for its new professors. After hiring applicants, the department pays particular attention to their courses and is prepared to offer them assistance if necessary.

Even so, there has yet to be a young hire who requires additional attention, he noted.

“I actually think [our young faculty hires] are really good,” Malesky said.

Competing commitments

However, no amount of instruction in teaching changes the fact that faculty must balance their teaching with their research. Charbonneau explained that everyone addresses this balance differently.

“There’s not a single recipe that works for everyone nor every time,” he said. “Things are in flux between what’s happening in your class and what’s happening with your research, so there are always some compromises that have to be made on both sides.”

Glander noted that he was lucky to be able to conduct his fieldwork in Madagascar, Costa Rica and South America during the summer, which meant he could devote more time to his teaching during the semester.

“Ideally in my field, it would be preferable to be present with the nonhuman primates year-round, but that’s obviously not possible, and I have to work with that,” he said.

Astrachan said that although his research is based on pedagogy and curriculum, the grants he receives from the National Science Foundation are not necessarily specific to Duke, which makes it “a little tricky” to balance his teaching with projects using those grants.

Brian Hare, associate professor of evolutionary anthropology, noted the tradeoff between being an effective teacher and a researcher.

“Certainly, when you’re teaching, you’re not going to be able to write as many papers or submit as many grants," he said. "The problem is, [without teaching], you wouldn’t be able to recruit students to come work for you."

He explained that he specifically designs his classes to get students excited about the material covered so that he can recruit them to participate in his research.

Alberts said that teaching and research are intellectually "synergistic" activities. Although research tends to be more focused in two or three areas of a discipline, teaching forces you to “zoom out,” she explained.

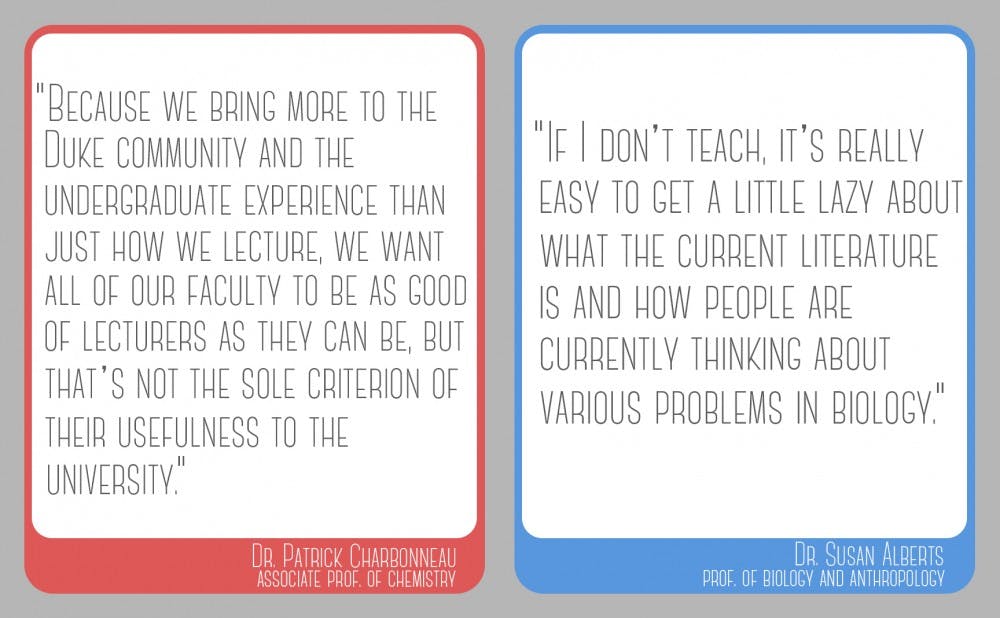

“If I don’t teach, it’s really easy to get a little lazy about what the current literature is and how people are currently thinking about various problems in biology,” she said.

John Aldrich, Pfizer-Pratt University professor of political science, mirrored Alberts' view, explaining that the broader context of his class helps inform the specific analysis required for his research.

In addition, faculty said that teaching can inspire new research questions and challenge them to think differently about their current research.

Charbonneau explained that whenever he teaches a class, it forces him to revisit the basics of his field, which in turn gives him new ideas.

Malesky said he believes it is part of his job to convey the passion he feels for his own research questions to his students, first by giving them the “foundational tools” they need to understand the material before demonstrating where the frontier of the discipline currently lies.

After mastering these foundational tools, a student is then ready to go into a lab, become a research assistant for a professor or write a thesis, Malesky explained.

Astrachan called the balance between research and teaching a false dichotomy, explaining that he probably spends more time in departmental meetings and other service to the University than he does in the classroom.

Faculty also have commitments in addition to academia, he noted.

“Outside of Duke, [faculty] might have hobbies, family,” Astrachan said. “I think most people have several things that they balance.”

But Duke professors are up to the challenge, noted Warren S. Warren, James B. Duke professor and chair of Physics, adding that Duke “naturally attracts people who enjoy making that balance.”

Becoming better teachers

Along the way to mastering this balance, faculty have sought to improve their undergraduate teaching in a variety of ways.

Alberts explained that faculty might observe their colleagues in the classroom, ask them directly about their teaching styles or seek out personal instruction to further improve their teaching.

Charbonneau echoed Alberts’ view, explaining that casual conversations during committee meetings, faculty dinners and other collegial gatherings build up over time to gradually improve the quality of one’s teaching.

Becoming a better teacher also comes from experience as well as how many times you have taught the material, he noted.

For example, Warren explained that in science classes an instructor usually teaches the same class for three to five years, so they build on their experiences.

Glander took an alternative approach to hone his teaching. He said that he would directly evaluate his own performance by asking students in the earlier classes of his career how he could get future students more interested in the material. To supplement this feedback, he also videotaped his own lectures.

“It was an eye-opener watching those video tapes because I could see a lot of issues,” Glander said.

Charbonneau praised Duke for allowing him to experiment with different forms of teaching and for encouraging him to take risks in the classroom.

“One of the reasons we became faculty is because we liked learning in various forms,” he said. “Being able to teach a class in which I get to learn myself is a way I’ve been able to become a better teacher.”

Challenges and chores

Although faculty discussed how teaching can be rewarding, they also voiced struggles they face inside the classroom.

Charbonneau said that he has heard students ask why Duke faculty are not better in the classroom.

“Because we bring more to the Duke community and the undergraduate experience than just how we lecture,” he said. “We want all of our faculty to be as good of lecturers as they can be, but that's not the sole criterion of their usefulness to the University.”

Charbonneau explained that if he had infinite financial resources, he would bring on more teaching assistant support to enrich the learning experience beyond the classroom and offload part of his responsibilities like grading.

Several others noted that grading is one aspect of teaching they tend to dislike the most.

“I hate grading mostly because I care more about whether students learned the material than calculating their specific rank in the class," Malesky said.

Aldrich described grading as a “chore,” adding that he often feels like it requires him to pass judgment on his students when there has not actually been enough time to pass judgment appropriately.

He added that he would like to see more students taking the initiative to engage with faculty outside the classroom and not just to talk about whether a project should have earned a “B” instead of a “B-.”

Glander said that his least favorite part of teaching was having students complain about their grades.

“If students are one tenth of a point away, they often feel that they are entitled to the remaining one tenth of a point," he said. "And I always tell them, ‘you earned this many points,’ and I’m not going to bump them up."

‘An incredible privilege’

Regardless of these negative aspects of the job, professors reflected positively upon their teaching experiences at Duke.

Alberts said that the opportunity to teach at Duke remains an “incredible privilege.” Her students are bright, dedicated and curious, she added.

Warren also praised the quality of students he has taught at Duke.

“Teaching smart undergraduates, such as the ones I have had at Duke or Princeton, is particularly rewarding,” he wrote.

Astrachan said that he enjoys watching his first-year students change over time at Duke and seeing what his seniors have accomplished along the way.

Observing the interaction among intellectually curious domestic and international students is also fun, Malesky said.

He added that he loves creating and pursuing new knowledge, and then being able to pass this along to his students.

Other faculty seek ways to give back through their teaching.

For example, Hare said he wants the same opportunities for his students to get involved with research that he had as an undergraduate.

“That moment of being asked to participate in making big discoveries as a sophomore, that was life-changing for me,” he said. “That’s the best part of teaching—trying to replicate what was given to me years ago.”

Charbonneau noted that teaching was the reason why he wanted to become an academic in the first place.

“I really like to learn about what I do from my research, but one of my favorite things to do is then to transmit that enthusiasm to my students,” he said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.