We live in an era of walls. On the news we see walls conjured by ideologies and walls placed around our words, walls that defined our history and walls that some promise will do the same for our future. We as a society seem to have a pretty clear definition of what a wall is and what it can do, so we wield it confidently as both a symbol of protection and a threat to those who don’t share our beliefs, motivations and physical characteristics.

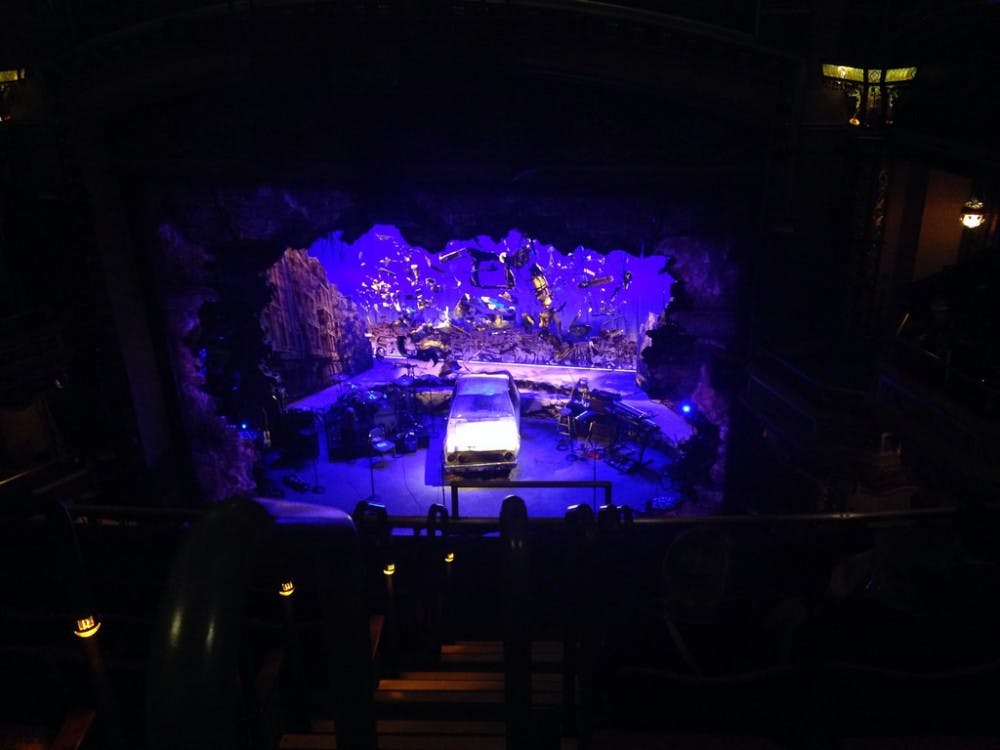

At the Durham Performing Arts Center last Thursday, the dynamic company and crew of the Broadway tour of the musical "Hedwig and the Angry Inch" encouraged audiences to reimagine that divisive term.

Through a diverse yet cohesive set of 70's glam pop-rock-inspired music Hedwig (played with similarly cohesive versatility by Euan Morton) narrates her personal journey from walled-off East Berlin to her present concert at the DPAC. Through sugar daddies and wicked little towns and through laments and queries on the origin of love, she explains how she came to be performing in N.C. She constantly reminds us that next door her ex-lover Tommy (also played by Mr. Morton) is playing a sold out show at the Durham Bulls Stadium.

Her wayfarer’s tale comprises convincing ad-libs on Geer Street and the N.C. Amendment HB2, witticisms on rock’n’roll and German philosophy (“you can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometime, you just might find, you get what you Nietzsche”), and a wonderfully overwrought joke about an ill-fated musical version of "The Hurt Locker." Hedwig is accompanied by her husband Yitzhak, a gender fluid drag queen played with remarkable range—vocal, emotional and physical—by Hannah Corneau, and a multitalented group of musicians that form both the pit and the peanut gallery.

DPAC is not constructed to serve the action to the cheap seats, but this production impresses in its capacity to deliver to those of us who paid to sit in the back of the house. The direction of Michael Mayer, of “Spring Awakening” and “American Idiot” fame, and the rock concert lighting and costumes illuminate and magnify every curl of the coiffes, every flick of the impossibly-high-yet-athletically-utilized heels.

The show’s technical and musical elements successfully highlight every palpable emotion of the titular figure, who has left the oppression of East Berlin for America only to find poverty and the news that the Berlin wall has fallen. We follow Hedwig and her band through all the shimmer, the shrapnel and the shame, guffawing along with the pitch-perfect political and sexual satire. By the time the powerful last refrain of “lift up your hands” reached us in the nosebleeds, we were waving our arms in triumph.

But "Hedwig" is more than just a rocking and uplifting way to spend an evening; it is a character study. It is an artistic study. It is a human study. John Cameron Mitchell, the creator and original Hedwig portrayer, has expressed that Hedwig is not a clearly defined trans woman. Rather, “she’s more than man or woman...she’s a gender of one and that is accidentally so beautiful.”

In the second half of the show—the musical runs a comfortable and casual 90 minutes without an intermission—we experience a song called "Exquisite Corpse," which is accompanied by images of heads and torsos and legs violently interchanging and melanging like a radioactive rubik's cube. The exquisite corpse as first created by the surrealists in the early 20th century is a practice of automatic art, a piece that is created by no clear artist. Practically, artists draw different parts of a body or write different parts of a sentence and the resulting creation appears almost accidentally, almost by itself.

“A collage!” Hedwig and her band scream, “All sewn up! A montage!”

Hedwig spends much of her time defining herself by the suppositions of her lovers, the silhouettes of her wigs and the scalpels of her doctors. What ultimately emerges is a singularly authentic Hedwig, a work of art with no clear creator but herself. She is at once art and artist, her scars—more clearly emotional than physical—despite a surprisingly fun song about her botched (and forced) sexual reassignment surgery—symbolizing a self-discovered beauty out of external violence. A strong expression of unity in the place of a divide.

Yitzhak reminds us that when the Berlin Wall fell, people didn’t know who they were anymore. Hedwig, who cannot be defined by the walls of any term of identity, is clearly just as lost without it. What should guide us in our reprised era of the wall? It can be argued that even a bridge is still a line by which a dichotomy is defined.

In this musical explosion of free—but not unquestioned—love that is sweeping through various live theater houses across the nation, we are reminded that bridges still stand as a symbol of two sides, just as a scar signifies a healed wound that must forever tell the story of its former pain. Hedwig reminds us that the Cold War may be over but division still exists: the rhetorical, the socially constructed and the physically real.

She is no prophet, no solution to our walled times, but Hedwig stands, defining herself with the strength of the undefined. At this riveting rock party Hedwig may be both the generous host and the shadowed skeleton in the closet, but she is also the door that stands between them: a symbol of division repurposed as glittering multidentity. It is from this physical and national state that she taunts and titillates us. Try to tear her down.

Kyle Alderdice, Trinity '16, is a guest Recess contributor.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.