As one of his first actions taken as president, Donald Trump reinstated what is known as the "global gag rule," and practitioners fear maternal mortality rates will now take a turn for the worse.

Trump signed the executive order reinstating what is formally known as the Mexico City policy just four days after taking office. His doing so did not come as a surprise—since the Ronald Reagan administration, the policy has been reinstated and repealed every time a new Republican or Democratic president has taken office.

The policy prohibits American family-planning funds from going to any foreign organization that provides counseling or referrals for abortion or advocates for abortion access. Critics call it the "global gag rule" because they argue it hinders doctor-patient communication, but its supporters argue that it will lead to a decrease in the overall abortion rate.

Practitioners with hands-on experience working with women in Africa argue that decreased access to abortions will only increase overall maternal mortality rates. Megan Huchko—associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology and global health—explained that the policy increases the number of unsafe abortions.

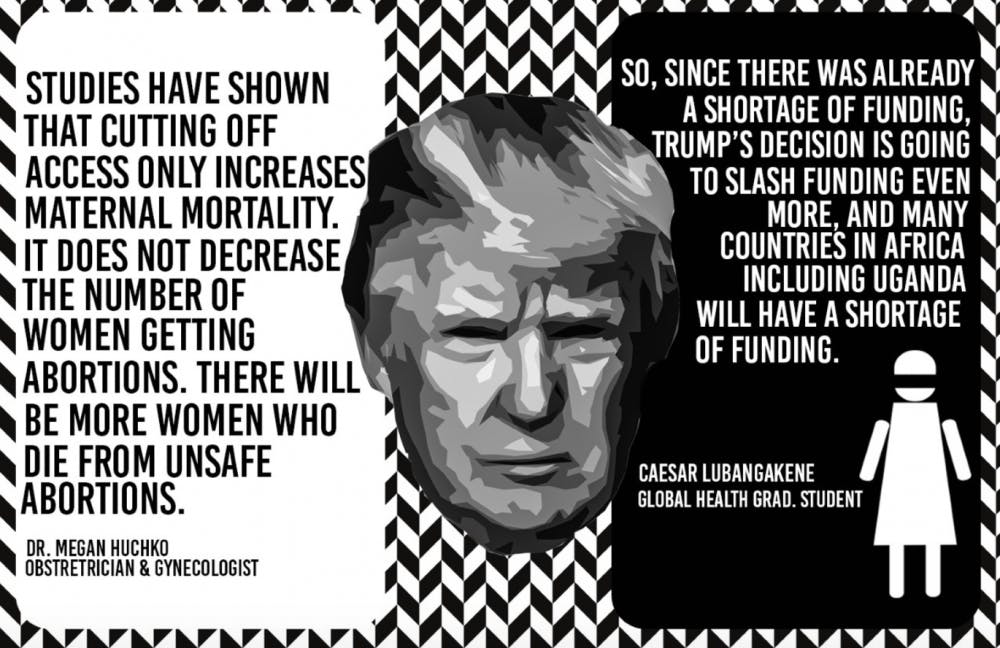

“Studies have shown that cutting off access only increases maternal mortality. It does not decrease the number of women getting abortions," said Huchko, who has worked in East Africa for the past 10 years dealing with poor access to reproductive services. "There will be more women who die from unsafe abortions."

Katherine Turner, president of international health consulting firm Global Citizen LLC, agreed with that assessment, saying she has seen women with "tremendous complications" die during her work in rural East Africa.

The policy is an obstacle on top of already conservative social views in Africa that can make getting an abortion difficult in the first place, said Caesar Lubangakene, a global health graduate student who has worked for a family planning organization in Uganda. The policy also comes at a time when national funding for health in Africa is already hard to find, a trend the World Health Organization has extensively documented.

"So, since there was already a shortage of funding, Trump’s decision is going to slash funding even more, and many countries in Africa including Uganda will have a shortage of funding," Lubangakene said. "Africa is a very conservative region. So many officials are happy about this decision. [The non-governmental organization] Marie Stopes International has been trying to step in and provide safe abortions, but many officials were unhappy with it. So they are probably happy with the conservative decision.”

Like the Mexico City executive order, other pieces of legislation in the United States limit abortion funding. For example, the 1973 Helms Amendment provides that "no foreign assistance funds may be used to pay for the performance of abortion as a method of family planning." The 1976 Hyde Amendment does something similar stateside.

Senior Hayley Farless, a cultural anthropology major studying reproductive rights, used these amendments to argue that Trump's executive order fails to achieve any significant purpose.

“A lot of people think this is a way to stop paying taxpayers from funding abortions, which is not true. The Helms Amendment outlawed that," she said. "A lot of studies have shown that this drastically increases the unsafe abortion rate. About 13 percent of maternal death results from complications of unsafe abortions. About 50,000 women."

But European nations may step up to combat the newly-reduced funding. The Netherlands has recently proposed an international abortion fund, for example.

The goal of this would be to make up for what the U.S funds were providing to the NGOs, Turner and Farless both noted.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.