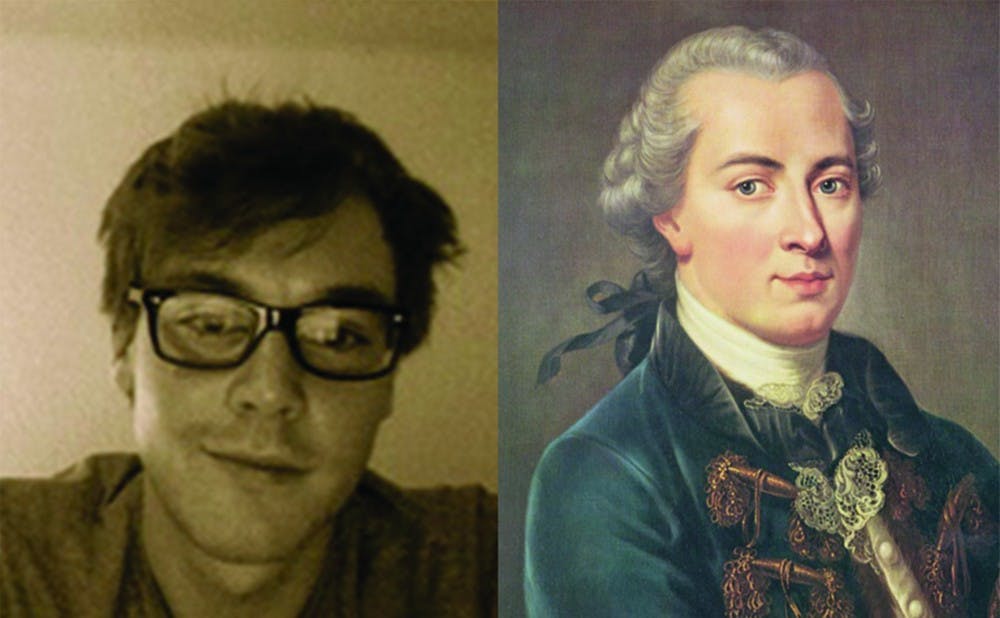

New research has called into question one of the most famous principles of German philosopher Immanuel Kant.

In a recent study, Vlad Chituc, an associate in research at the Social Science Research Institute at Duke and Paul Henne, a graduate student in philosophy, challenged Kant’s widely accepted idea that “ought implies can,” or that our moral obligations cannot exceed our abilities.

The researchers found that contrary to what most philosophers might expect, participants in their studies said they thought that whether or not someone “ought” to do something depended on concerns related to blame, rather than ability.

“We were flooded with emails from angry professors,” Chituc said. “People feel very strongly about Kant.”

Their psychological study, which will be published in the May issue of the journal Cognition, included 79 participants who took an online survey in which they were given fictional stories about why people failed to keep their promises, such as not giving someone a ride because of car troubles or purposefully ditching a friend.

When the promise was broken intentionally, subjects generally believed the person still “ought” to fulfill it, even though in some cases it was impossible. The researchers used the results to establish that people believe that others “ought” to do something if the are to blame rather than if they “can.”

“The simplest way to put it is philosophers have assumed that ‘ought’ implies ‘can.’ So it cannot be true that you ‘ought’ to do something if you cannot do it,” said Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Chauncey Stillman professor of practical ethics at Duke. “We gave examples where the subjects said that the person ought to do it even though they knew that the person could not do it. A lot of people think that’s not fair but I think that’s the way morality is.”

The researchers said their study was sparked during Spring 2014 by a conversation between Henne and Chituc in the Pinhook, a bar in downtown Durham, when Henne asked Chituc, “Does ‘ought’ imply ‘can’?” and Chituc responded, “Of course it does!”

Yet in the coming weeks, after reading several studies, the pair discovered that this principle depends on the meaning of the words.

The two researchers created their own study to test this idea with Armstrong, who first challenged Kant’s theory in 1984 when he outlined a series of thought experiments that showed “ought” does not always imply “can.”

“Vlad and Paul came to me and suggested that we could test this empirically,” Armstrong said, noting that he was nervous the study would contradict his original hypothesis.

“It would have been embarrassing, but luckily the research came out my way,” he noted.

The three researchers, along with Felipe De Brigard, an assistant professor of philosophy, hashed out a study, “crammed in a small office, taking notes on phones,” Chituc explained.

Armstrong mentioned that many of the people who were upset by the article were not so much angry about the data as they were about the researchers’ interpretation of Kant. He explained that there are frequently disputes over how to interpret Kant because his writing is obscure.

“If it turns out he never really said that ‘ought implies can,’ then fine, we didn’t refute Kant, but it’s still a common view that many other people share,” Armstrong said.

Some critics of Chituc and Henne’s study question the methodology they used.

Philosophers generally conduct studies by asking themselves questions rather than surveying people who are not professional philosophers.

At Duke—unlike most institutions—several researchers use surveys to reflect on philosophical issues, Armstrong noted.

“[This is] not necessarily to settle or give the last word on those issues but to think in a new way about those new issues,” Armstrong explained.

Chituc and Henne are currently doing follow-up studies and will present their findings at the Society for Philosophy and Psychology in early June.

In February, The New York Times published a piece by Chituc and Henne in its Gray Matter column, detailing the implications of this research.

“People were rolling over in their graves after that article,” Henne said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.