Editor's Note: Califf was officially confirmed by the Senate Wednesday morning.

Dr. Robert Califf, former vice chancellor of clinical and translational research, has moved further down the path to becoming the commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration after a Monday procedural vote in the U.S. Senate ended debate on his nomination.

Nominated for the position in September by President Barack Obama, Califf attended a series of hearings with congressional committees and meetings with individual Senate members to assess his qualifications. In early January, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions unanimously approved Califf’s nomination, which has historically indicated that the voting process for nomination will quickly proceed on the Senate floor.

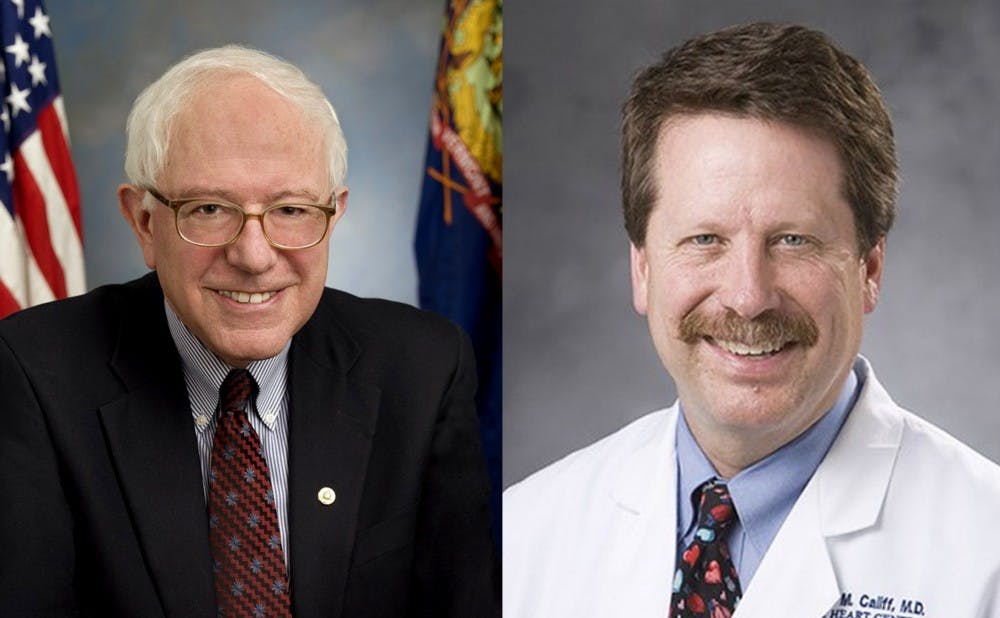

Some congressional leaders have expressed concerns about Califf, however, citing reasons ranging from his previous ties with pharmaceutical companies while at Duke to his stance on labeling genetically engineered fish. Several senators—including presidential candidate Bernie Sanders—had placed a hold on his nomination, indicating that they intended to filibuster a vote.

Despite the controversy, many Duke faculty and administrative leaders have remained steadfast in their support for Califf.

“It looks to me as though the controversy is centered around the extensive industry contracts that [Califf] has had until now as opposed to his vision that the future of research and drug development is going to be collaboration with the industry,” said Lawrence Baxter, William B. McGuire professor of the practice of law. “There’s a lot to be gained by academics being immersed in what the companies are doing and a lot to be gained by companies in sponsoring what academics do. I think the real key is looking at safeguards to protect the public.”

Monday’s Senate vote was 80-6 in Califf’s favor, ending opponents’ ability to filibuster the nomination and easily clearing the 60-vote threshold he needed. Those who oppose Califf now will only have at most 30 hours of speaking time to explain why they want to block him.

Michael Gerhardt, Samuel Ashe distinguished professor in constitutional law at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Law, noted in an email that the majority leader can slightly delay a final vote after the cloture is obtained but cannot postpone the vote indefinitely. The final vote could come as soon as Tuesday.

The vote will likely not be divided along partisan lines, as both Democrats and Republicans have expressed dissatisfaction with Califf. Sen. Edward Markey has placed a hold Califf’s nomination in order to force the FDA to reconsider its stance on the opiate approval process and Sen. Lisa Murkowski has similarly done so for his stance on genetically modified fish labeling. Sanders has expressed concerns primarily about Califf’s consulting experience and role in recruiting pharmaceutical funding while at Duke.

“Dr. Califf’s extensive ties to the pharmaceutical industry give me no reason to believe that he would make the FDA work for ordinary Americans, rather than just the CEOs of pharmaceutical companies,” Sanders noted in a statement.

Sen. Elizabath Warren also expressed disapproval of Califf’s nomination in November, saying Califf, a cardiologist by training, is too connected to the pharmaceutical industry. Soon after the HELP Committee’s approval of the nomination, however, she reversed her position, stating she was “satisfied that [Califf] has conducted himself with integrity as an academic researcher.”

Baxter said that the concerns of legislators like Sanders and Warren center around the concept of regulatory capture, a situation in which an industry has undue influence on its regulators. Worries about regulatory capture in the United States government grew significantly after the financial crisis of 2008, he explained.

“In my personal opinion, I don’t think we can avoid a very substantial degree of industry influence because we need experts,” Baxter said. “Only someone who understands the whole process of drug approval is going to be able to run the FDA in a sensible fashion.”

During the committee hearing Nov. 17, Sen. Lamar Alexander, chair of the HELP committee, questioned Califf on a variety of topics, such as whether pharmaceutical companies should be allowed to advertise unofficial uses of their drugs under the first amendment and how the FDA should implement its regulations in auditing private pharmaceutical companies.

Alexander also asked Califf about his stance on how regulation might impede innovation in the pharmaceutical industry, claiming that a lecture Califf gave in 2014 described regulation as a “barrier to disruptive innovation innovation.” In response, Califf was adamant in stating that regulation is critical to the process of developing medicine.

“I have never stated, implied, or argued that the barrier should be lowered or removed, ” Califf replied. “The belief that we should have evidence of benefits and risks before marketing in health care has been a driving force in my career and a motivation to develop more effective, efficient and unbiased ways of conducting generalizable clinical trials and implementing quality systems for learning in health care as a focus of my academic and practical work.”

Dr. Ross McKinney Jr., chair of Duke’s Conflict of Interest Committee and professor of pediatrics, wrote in an email that the Research Integrity Office takes a wide range of steps to ensure that the University’s researchers are not influenced by pharmaceutical interests.

“In order to assure consistency with mission, the Office of Corporate Research Collaborations, run by Gavin Foltz [associate dean and executive director of the Office of Corporate Research Collaborations], reviews the projects and signs [each funding] contract for Duke, McKinney explained. “The faculty member does not sign—the project is with Duke, not the individual.”

McKinney also noted that the University is continually aware of the consulting contracts many medical faculty have with the pharmaceutical industry and wrote that the RIO is generally in favor of such relationships.

Duke faculty such as Califf are allowed to spend one day a week consulting with private companies and are required to disclose their relationship once they receive $5,000 in consulting fees, McKinney said. Faculty are also restricted in their ability to serve as a principal investigator at Duke once they receive more than $25,000, he added.

McKinney noted Califf followed the University’s guidelines during his time at Duke.

“We were very aware of Dr. Califf’s consulting with the pharmaceutical industry,” he wrote. “He kept us informed and at no time crossed any lines in the nature of how he balanced his Duke professional role and the consulting work he did with industry.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.