Vice President Joe Biden joined a panel of experts to discuss barriers to curing cancer Wednesday afternoon.

Last month, Biden announced a new initiative for cancer research—a “moonshot” that aims to speed up the process of finding cures for cancer. During his Duke visit, Biden engaged in a roundtable conversation with 10 other panelists about a number of issues, placing special focus on the main challenges facing researchers and policymakers today. More than 100 people attended the invitation-only event, including physicians, administrators and scientists. Topics that were touched upon included using big data to enhance research, addressing disparities in patient care and increasing access to clinical trials.

“Together, we can find a lot of answers to these questions, and in the process I think we can end up developing game-changing treatments and delivering them to anyone who needs them,” Biden said. “We’re not looking at incremental change. What we’re trying to do is end up with a quantum leap on the path to a cure.”

The goal of the initiative is to double the rate of progress, making “a decade’s worth of advancements in the next five years,” Biden said. Nonetheless, the vice president repeatedly mentioned that he was not “naïve” and that developing a cure would be a long and difficult process.

“I’m not looking for a silver bullet. There is none,” Biden said.

The vice president said he saw big data as “the greatest hope” for cancer research, adding that genomic information which once required countless hours and dollars to extract could now be accessed easily as a result of improved technology.

Dr. Shelley Hwang, chief of breast surgery at the Duke Cancer Institute and professor of surgery, noted the difficulty of analyzing massive amounts of data, much of which is extraneous or unusable. A project that Hwang is part of aims to organize patient data earlier on in the clinical process in order to simplify later data analysis and sharing.

One barrier to data sharing is the lack of standardization of data elements in the medical field, a problem that the National Cancer Institute unsuccessfully attempted to tackle several years ago, Hwang said.

“It’s important for us to all have the same language,” she said. “When we’re talking about a broken leg or a fracture, it means the same thing. We need to be able to define it in a way that when we pull the data out, it is recognized as the same thing.”

A related issue has been the lack of communication between experts in different disciplines, creating “silos” that prevent researchers from building upon each other’s work. In the past, Hwang noted, surgeons, oncologists and scientists failed to reliably communicate with one another.

“We’re going to make sure the information is being shared so that an oncologist in Fayetteville can access information from a world-class institution like Duke,” Biden said.

Part of the solution will be the increased funding for research provided by the federal government, Biden noted. The initiative will include $195 million in new research funding for Fiscal Year 2016 and $755 million for the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration in FY 2017.

“We don’t think the federal government is the only answer to this,” Biden said. “This is a question of, how can we be helpful? What can we do to work with the community to make more progress? Where you view the government as a bureaucratic stumbling block, I want to make sure that stumbling block is eliminated.”

READ: Storify: Vice President Joe Biden visits Duke, attends cancer panel

Another issue that was discussed was that of racial disparities in healthcare access. Gayle Harris, public health director for the Durham County Department of Public Health, pointed out that people of color often receive late diagnoses and are also often reluctant to enroll in clinical trials.

“In the African-American community, people still go back to [the] Tuskegee [syphilis experiment]. There is a lack of trust,” she said.

During the discussion, Biden posed several questions to the panelists, including one about how to reach larger populations of patients for clinical trials.

“We have patients who would willingly and gladly participate in trials. They want to be part of this moonshot,” said Dr. Kimberly Blackwell, professor of medicine, assistant professor of radiation oncology and a renowned breast cancer researcher. “They are in line, they are ready to break down those barriers, they are ready to participate in the clinical trials.”

Blackwell noted, however, that lack of collaboration between pharmaceutical companies creates silos that lead to wasted resources.

One panelist, Niklaus Steiner—director of the Center for Global Initiatives at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—shared the story of his daughter Sophie, who passed away at age 15 due to cancer. Steiner and his wife have since founded the Be Loud! Sophie Foundation to support adolescent and young adult cancer patients, an age group that he noted is sometimes overlooked by health care systems. Steiner’s story prompted Biden to reflect on tragedy in his own life, including the death of his son Beau, who died of brain cancer at age 46 last May.

“We all have had our experiences with death and tragedy,” Biden said. “When you’ve been through it, you have a different perspective.”

The other speakers at the roundtable were Dr. James Atkins, a medical oncologist; Susan Braun, chief executive officer of The V Foundation for Cancer Research; Dr. Howard Eisenson, chief medical officer of the Lincoln Community Health Center; Brenda Nevidjon, chief executive officer of Oncology Nursing Society; Dr. John Sampson, Duke’s chair of neurosurgery; and Stephanie Wheeler, associate professor at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

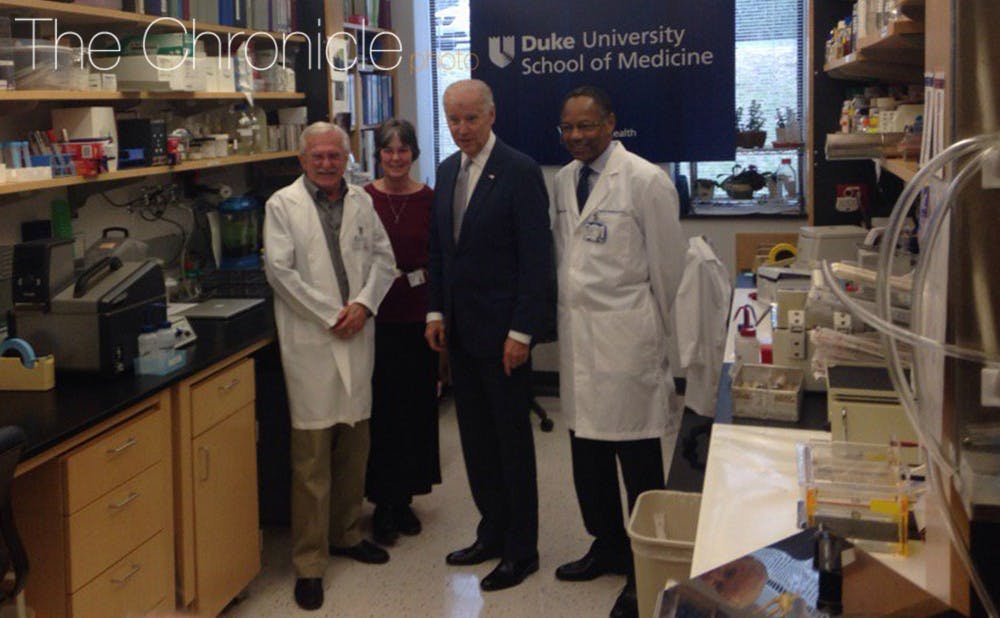

Prior to the roundtable discussion, Biden visited the lab of Paul Modrich, James B. Duke professor of biochemistry and Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, accompanied by Dr. A. Eugene Washington, chancellor for health affairs and CEO of Duke University Health System. Before briefly chatting with Modrich and congratulating him on his recent Nobel Prize victory, Biden also met with Sampson and Dr. Matthias Gromeier, associate professor of neurosurgery.

During his visit, Biden talked to Stephanie Lipscomb, who had a brain tumor that was successfully treated by a novel poliovirus therapy at Duke Hospital. The novel treatment—which uses a safe, modified form of polio to alert the immune system to the presence of cancer cells—was developed by Gromeier. Based on Gromeier’s work, Duke researchers are currently in the process of testing the treatment on other forms of cancer, including prostate cancer.

The moonshot initiative emphasizes development in immunotherapy approaches like Duke’s, in addition to other cutting-edge research in combination therapies and genetic screening for early detection.

“The science is ready,” Biden said. “Much more has to be done, but I believe we can make much faster progress...if we see greater collaboration, greater sharing of information.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.