Researchers at Duke have helped develop a first draft of the most comprehensive map of biological evolution ever made—the Open Tree of Life.

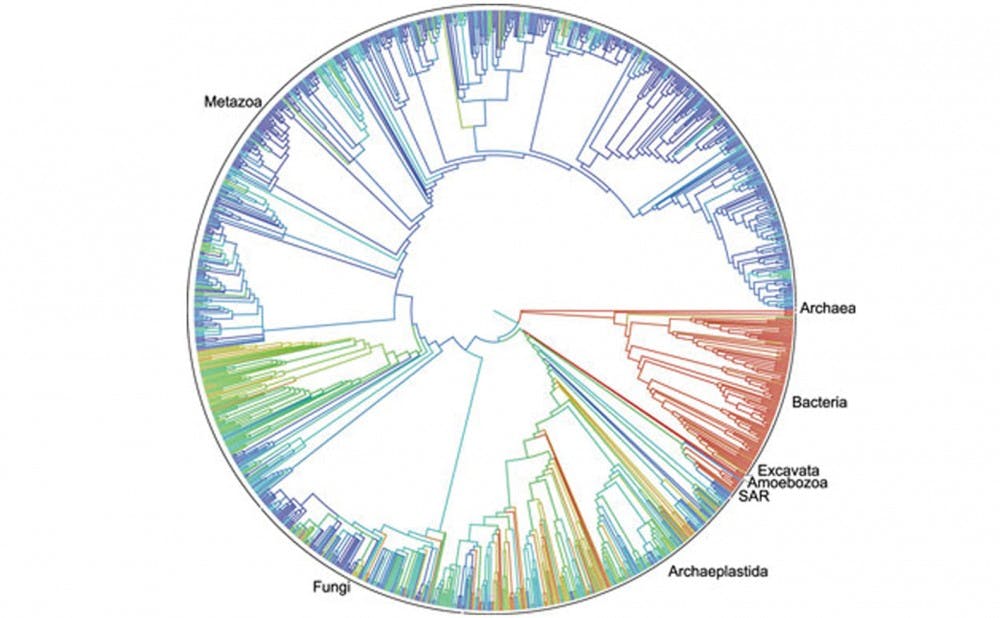

In collaboration with 10 primary investigators from across the country, Duke faculty have been instrumental in assembling the Open Tree of Life, an undertaking that has mapped the evolutionary histories of more than 2.3 million species. The Open Tree of Life has systematically incorporated existing trees into an extensive phylogenetic tree—which characterizes the evolutionary relationships between groups of organisms through branching networks. In addition to presenting a “supertree” of life, the researchers have enabled users to search for conflicts between existing trees that could be the subject of future research.

“There are a couple of things that make Open Tree of Life unique,” wrote Karen Cranston, a principal investigator at Duke who has been involved in the making of the supertree, in an email. “First, it aims to be comprehensive. The tree contains 2.3 million tips, making it orders of magnitude more complete than other tree of life projects. Secondly, we are building this tree by writing algorithms that combine published trees, not by inferring trees directly from DNA or other data.”

Cranston and her fellow investigators were awarded a grant to develop a “supertree” after a 2011 National Science Foundation workshop focused on solving the major challenges associated with a comprehensive tree of life.

“The NSF had an interesting model for this program where researchers could apply to come to a meeting where radical and risky tree of life research was to be discussed,” wrote Stephen Smith, a principal investigator at the University of Michigan, in an email.

The phylogeny shows how the various forms of life on Earth were derived, depicting evolutionary relationships through a branching structure that resembles family trees on services like Ancestor.com.

Cranston, however, noted that the published phylogeny does not fully reveal the dissent among the researchers that study the evolutionary relationships between organisms—a result of the vast number of phylogenetic trees the project has stitched together.

“Our database contains many conflicting trees, so while the tree presented on the website is only one way to summarize this data, we have the underlying data that would also [allow] us (or others) to dig deeper into alternate resolutions,” she explained. “We are working now on ways to report or visualize the ways that the input trees agree and disagree with each other and with the synthetic tree and taxonomy.”

Smith, whose lab at Michigan focuses on developing computational tools to study evolution, explained that the collaborative aspect of the project was one of the key challenges the researchers faced.

“[My lab’s role in] this project was [to] work on new computational problems, but we are also interested in the biological results,” he wrote. “In order to communicate with so many people, we used a lot of tools and frequent conference calls. It is always difficult to get all these people together but we managed to make it work pretty well.”

The design of the initial phylogeny allows other researchers to easily contribute to the Open Tree of Life, wrote Jonathan Rees, a software engineer in Duke’s biology department, in an email.

“A big concern has been the future prospects for the project,” he explained. “We want the work we’ve done with the phylogenetic trees to be of use to the community for years into the future, and we need the community’s help in order for the tree collection to grow. To these ends, one tactic we’ve used has been to put as much data and code as we can [online] so that anyone can see what we’re doing and run with it if they want.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.