Duke University professors have been awarded a total of $3.7 million from the National Institutes of Health to fight cervical cancer in developing countries.

Nimmi Ramanujam, Robert W. Carr Jr. professor of biomedical engineering and global health, and Dr. John Schmitt, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, will use the money to further develop a new portable colposcope, a tool used to diagnose cervical cancer. The grant—which was announced in August—will enable the team to work with industry and nonprofit partners to conduct screenings for cervical cancer in regions such as East Africa, India and Peru.

“The goal of our research project is to solve a significant unmet clinical need in resource-poor settings,” said Marlee Krieger, research project manager in Ramanujam’s lab. “In areas like Tanzania, Kenya, India and Peru, the incidence and mortality rate of cervical cancer is still very high due to limited access to screening and treatment.”

Schmitt explained that his team is tackling this issue because cervical cancer is the leading cause of death for women in parts of Africa and Asia. Additionally, doctors know the biology of cervical cancer better than any other type of cancer. In more developed countries, the incidence of cervical cancer has dropped because of early screening techniques such as the Pap smear.

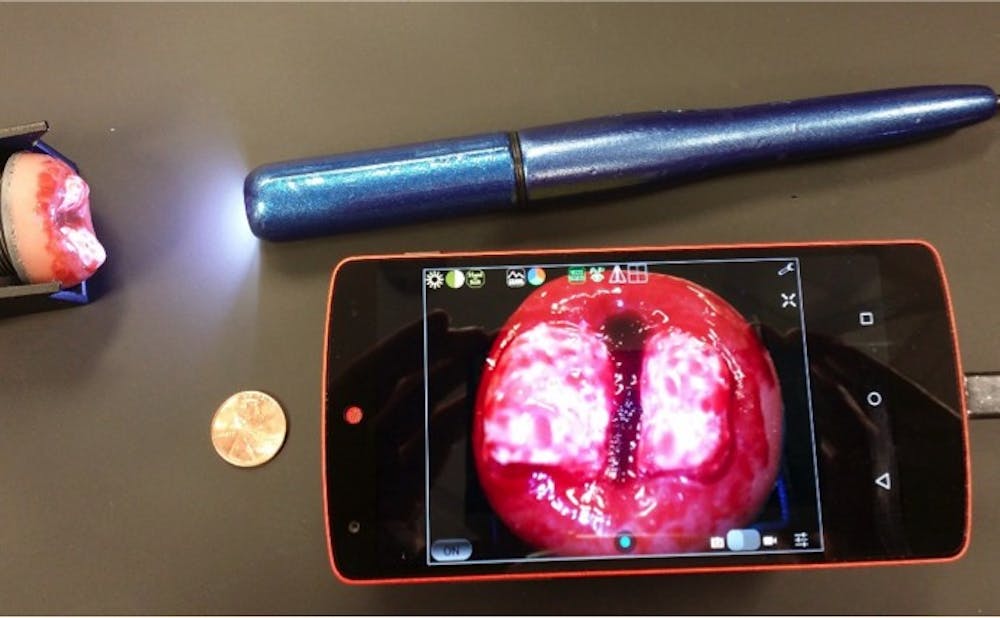

Ramanujam and her team have developed a “culturally appropriate” solution: a hand-held colposcope for cervical cancer screening in resource-poor areas called the Point of Care Tampon—or POCkeT. The system consists of a five-megapixel digital camera that is used to magnify the cervix during a screening technique called visual inspection. Krieger said that compared to standard colposcopes, their hand-held system is low-cost, easy to use and requires minimal training.

She added that the process of designing a culturally appropriate device involves understanding the core cultural values, beliefs and perceptions of a specific location and incorporating those beliefs into their design. Additionally, Krieger said that they have designed the device to be speculum-free because speculums are stigmatized in many cultures and religions.

“During Pap smears, the doctor uses an instrument called a speculum to widen the vagina,” Schmitt said. “Women find it to be intimidating and uncomfortable.”

The grants have allowed Ramanujam and Schmitt to form a multidisciplinary team and test the device in relevant clinical settings. Within Duke, they are collaborating with the School of Medicine, the Nicholas School for the Environment and the Global Health Institute. In addition, they work with a number of other academic institutions, medical centers and corporate partners around the world.

“We have engineers designing the colposcope; software engineers designing mobile applications so doctors in the countries can easily assess the images; global value chain analysts making sure that the final device can be marketed in developing countries; and stakeholder assessors confirming that the device is culturally appropriate,” Krieger said.

She added that one of the biggest challenges with coordinating such a large interdisciplinary team of people is making sure that they meet set deadlines, as team members are heavily dependent on one another.

The device will be implemented abroad starting in January 2016, when a small pilot study will be conducted in Peru.

“The hope for the future is that we won’t see another woman die from cervical cancer because it is so easily treatable,” Krieger said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.