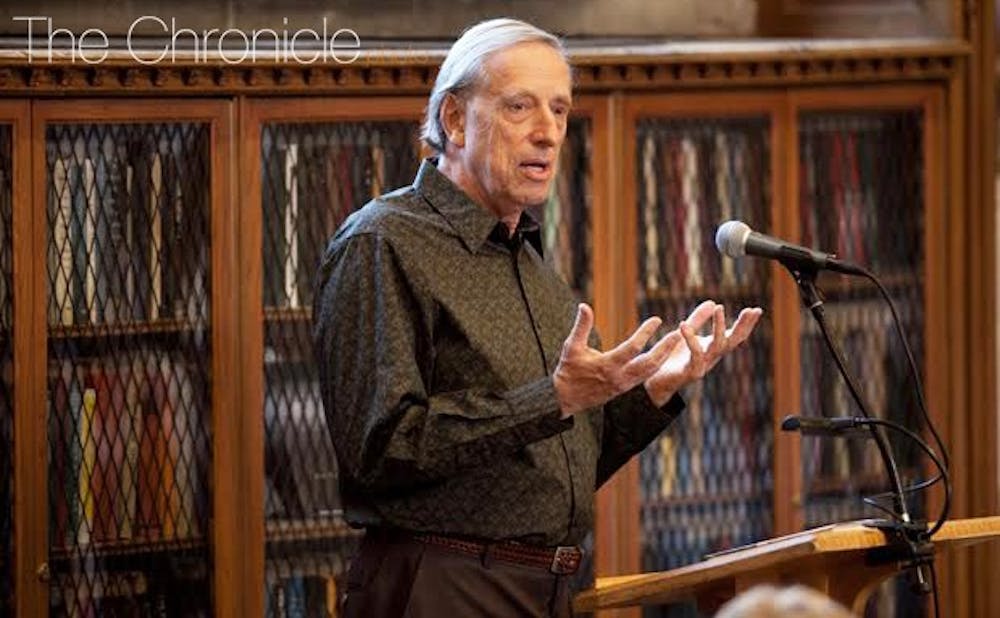

Ariel Dorfman, Walter Hines Page research professor of literature, has written more than 25 books in his career. One of his most famous plays, “Death and the Maiden,” has come under scrutiny recently at a New Jersey high school. Parents at Rumson-Fair Haven Regional High School are petitioning to remove the play from mandatory reading lists due to its vulgar language and imagery. A counter-petition to keep the piece has also been started. The Chronicle’s Anupriya Sivakumar sat down with Dorfman to discuss the implications of his work, the problem of censorship in society and how his experience as an exile from Chile during the regime of Augusto Pinochet has motivated his career.

The Chronicle: Why are parents attempting to censor your play “Death and the Maiden”?

Ariel Dorfman: This play has been one of the most performed plays in the world. Not thousands, but millions of students have read this book. So I was shocked when I read that there was a petition circulating to have that suppressed. In this particular case, they seem to be objecting to the fact that 17 and 18-year-old students at school would be subjected to language that was vulgar or coarse. This is a play where a torture victim is sexually abused by several tormentors and by her doctor during her detention. So the reason why her language is so sexual is because of what was done to her. If she skirts those, then she cannot liberate herself from the demons of her past. The language in this case is essential to the story and to her therapy.

That language is not what makes this play an interesting text for these students, because it deals with memory, with justice and the transition to democracy. It deals with women taking power. She cannot use civil words because what was done to her was not civilized. So, clearly you cannot read the text or watch it on screen or see it on stage without those words. And if those words offend people, they should be more offended by what is being done to this woman and what is being done to thousands and thousands of other women, either prisoners or in other circumstances—who are habitually being raped during war, during catastrophe and oftentimes in domestic circumstances.

What the parents are really saying—and by the way they are a minority in that community—is that one should suppress these books because they are offensive or they lead to misbehavior, that students are acting out and they are learning in my book how to deal with sexuality in some strange way. The real problem behind this is, regardless of my own text, who decides what should and shouldn’t be read in school? I understand that parents want some input into what their kids are reading or talking about, but the right way of dealing with that is to read the texts along with their children and have a discussion about what these things are, so that sexual references are put into the context of the literature. Because you could say the same thing about Shakespeare, about Dante, about the Iliad. There are so many ways to object to any book ever—“The Catcher in the Rye” and Toni Morrison are up for censorship. There’s always going to be something that offends people in books. Very often, it is that which offends us which most opens our minds.

TC: Have any of your other works been controversial?

AD: I find myself in the polemic of another issue at UNC. There was a class on the literature of 9/11. A freshman decided that the course only spoke from the point of view of the terrorists. One of the books that he was objecting to was called “Poems from Guantanamo: The Detainees Speak”. I wrote the afterword to that book. So I feel as if I’m being doubly suppressed. It’s almost as if they’re saying that those detainees, who haven’t been charged with anything, and were kept for years without trial, are not human. It’s almost as if the humanization of them—seen in the fact that they write poems—is a sin.

There’s a tendency to be scared of that which we don’t understand. “Death and the Maiden” is about silence. It’s about the silencing of a woman who has been raped and is speaking up and acting out against it. Anyone can be an accomplice to that suppression. This indicates that people don’t really understand what literature is about, what dictatorship is about and what liberation is about.

TC: What do you think the value of literature is and why is preventing censorship important?

AD: Literature has many functions. Literature will always stir you up to go into situations which you understand to be yours because they’re human, yet you haven’t experienced it. It allows us to expand our imagination above all things. And oftentimes that imagination deals with forbidden themes—themes that are perilous, which are destabilizing towards our psyche and which change us deeply. Since the very start of literature, there has been a conflict with people of power who put aside those forms of the imagination which call into question the way the world has been constructed. I’m not saying that all literature is always critical. But many of the great works of literature are very critical of the way we live our lives, the way we dream, the way we relate to one another. Any attempt to restrict the freedom of our expression is an attempt to diminish our humanity. When the kids at this high school are forbidden from reading that book, that’s an assault on everybody’s freedom.

TC: How have your experiences in Chile contributed to your viewpoint?

AD: Chile has marked me very strongly because I participated in the democratic revolution and suffered along with my family and my friends and my countrymen. “Death and the Maiden” itself is the product of my meditation of what it means to have a transition to democracy. For instance, do we bury the past or do we assume the past? What if the past is so terrible that it will traumatize us and not allow us to sleep? These are a lot of questions that I ask that have affected my life.

TC: How has coming to Duke contributed to your work and what do you hope to bring to Duke?

AD: Duke gave me refuge while I was still in exile. I came to Duke for only a few years so I could go back and forth between Duke and Chile. Then I was arrested in Chile, deported from Chile and I decided to stay here rather than go back permanently. So Duke has given me sanctuary to write all my works. As for the future, I am retiring but I will remain as professor emeritus for many years.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.