After more than a decade of diminished funding, a bill awaiting Senate approval could revive the National Institutes of Health’s budget.

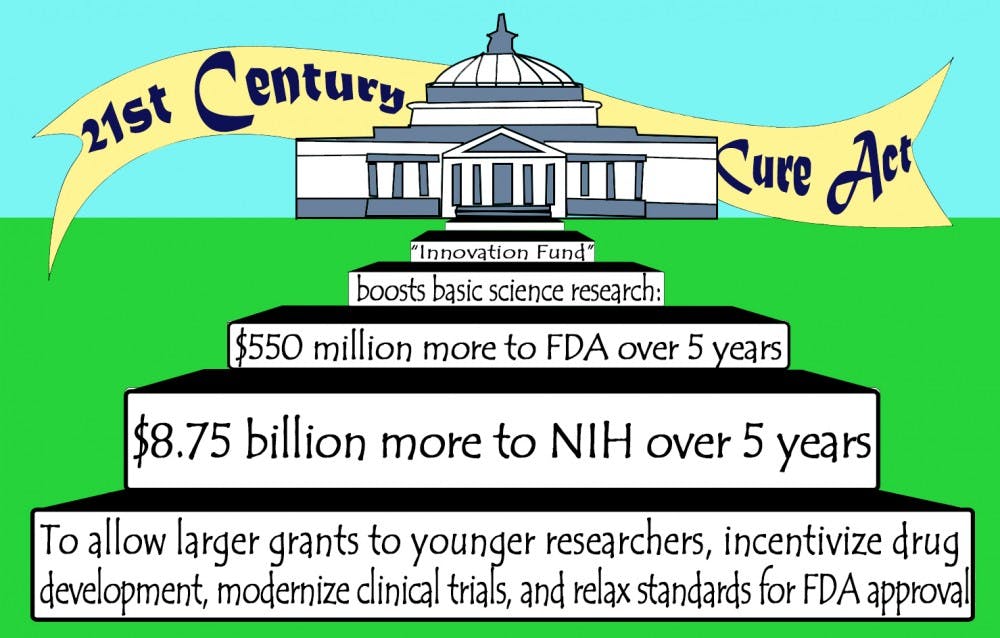

The 21st Century Cures Act draft—which the House of Representatives passed in a bipartisan 344-77 vote last month—stipulates that the NIH and the Food and Drug Administration will receive total increases in funding of $8.75 billion and $550 million, respectively, throughout the next five years. Certain aspects of the bill, however, are controversial among politicians, scientists and the public—especially its streamlined drug and medical device approval process for the FDA.

Since 2003, the NIH’s budget has seen only stagnant or decreasing numbers, so the 21st Century Cures Act comes at a critical point, said Steven Patierno, deputy director of the Duke Cancer Institute.

“[Lack of funding] has had a chilling effect on biomedical research in the U.S., and unfortunately at a time when we are poised to make some of the biggest breakthroughs ever in terms of our molecular understanding of disease and our ability to design drugs by utilizing precision medicine,” Patierno said.

The past decade’s funding cuts, along with inflation, have translated to a more than 20 percent loss in purchasing power for NIH grants and lower grant success rates. The struggle for resources in such a highly competitive environment has resulted in many top researchers leaving their fields, Patierno said.

“Biomedical scientists are competing for a much smaller pie, and with less purchasing power even if you do get a grant,” he explained. “What’s more scary is that we’ve lost a generation or two of young scientists who have chosen other fields because they see an uncertain future based on the decreased investment in biomedical research.”

The 21st Century Cures Act aims to boost funds for basic science research, spur innovation and invest in the next generations of scientists. The “Innovation Fund” sets aside $1.75 billion for the NIH each year for the next five years and $110 million annually for the FDA. The partly restored flow of funding will allow larger grants to be awarded to more researchers—especially younger investigators.

“By relieving the pressure that this intense and long period of resource restriction has produced, it allows younger scientists to compete for grants and help them get started in science,” Patierno said. “It will provide a psychological boost by energizing the research community which has been laboring under very difficult circumstances.”

The bill also hopes to incentivize the development of drugs for rare diseases, remove barriers that block sharing of health data for research, modernize clinical trials and direct funding toward several critical areas of research—including Alzheimer’s disease, precision medicine, the president’s BRAIN initiative and antibiotic resistance.

Patierno compared the government setting specific targets for biomedical research to NASA announcing efforts to get to the moon or sending a spacecraft to Pluto.

“The idea is an intensive period of resources and targeted research,” he explained. “It really facilitates collaboration between scientists, institutions and countries. Many minds brought to bear on a single problem—that is how major discoveries can be made.”

The most controversial aspect of the 21st Century Cures Act—and the one that will potentially encounter the most debate in the Senate—is its expediting of the FDA’s drug and medical device approval process.

To get drugs to patients more quickly, the bill proposes the relaxation of certain standards for FDA approval. For example, when evaluating a drug’s effectiveness, the FDA could use biomarkers such as tumor size instead of relying on long-term health outcomes in patients.

Patierno argued that the bill would mostly remove redundant bureaucratic barriers to conducting research, not patient protections.

“Most big research universities like Duke and [the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill] are very sensitive to maintaining patient protection, both physical health and privacy,” he said. “No one is advocating to remove that—we’re advocating to decrease the amount of paperwork and restrictions that slow the process dramatically.”

But other scientists see the lowering of FDA standards as risky for drug development.

“Aside from rare diseases and the few drugs that treat few people, if you’ve got molecules treating a lot of human beings, you want to be absolutely sure it works,” said Dr. Daniel Benjamin, faculty associate director of the Duke Clinical Research Institute and professor of pediatrics. “And if you don’t require companies to make sure they work, they’ll submit garbage for approval.”

Relaxing legislation for randomized and blinded clinical trials could harm patients, he added, noting that Duke conducts the most randomized, industry-sponsored clinical trials of any academic institution.

Benjamin said he believes the Senate will discuss and ultimately take issue with certain aspects of the expedited FDA approval process—leaving the outcome of the bill unknown.

Paul Vick, associate vice president for government relations for Duke Medicine, explained that the core conflict on this issue is between ensuring patient safety and getting cures to patients in need as quickly as possible.

“It’s been a lot of debate inside and outside Congress,” Vick said. “The key thing is, the Senate has a very different set of ideas, some in common with the 21st Century Cures and some not, so it’s not clear yet how they are going to manage this bill.”

Despite the Senate’s uncertainly, the bipartisan support exhibited by the House of Representatives reflects politicians’ increasing awareness of the importance of research and health.

“There’s been an enormous public cry from the general public and patients, from advocacy organizations,” Patierno said. “This groundswell of support has made its way to the offices and path of congressional representatives. I think they are poised to act.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.