With North Carolina's ban on fracking set to expire next year, Duke researchers are looking into the potential dangers of the technique.

Over the last several years, hydraulic fracturing—better known as fracking—has increased the potential to produce domestic oil and gas. The process uses high pressure water and horizontal drilling to break up shale beneath the ground and bring up natural gas. But Duke researchers have explored potential risks of the process, with their work becoming increasingly important as North Carolina holds public hearings on fracking and seeks to begin fracking tests in the fall.

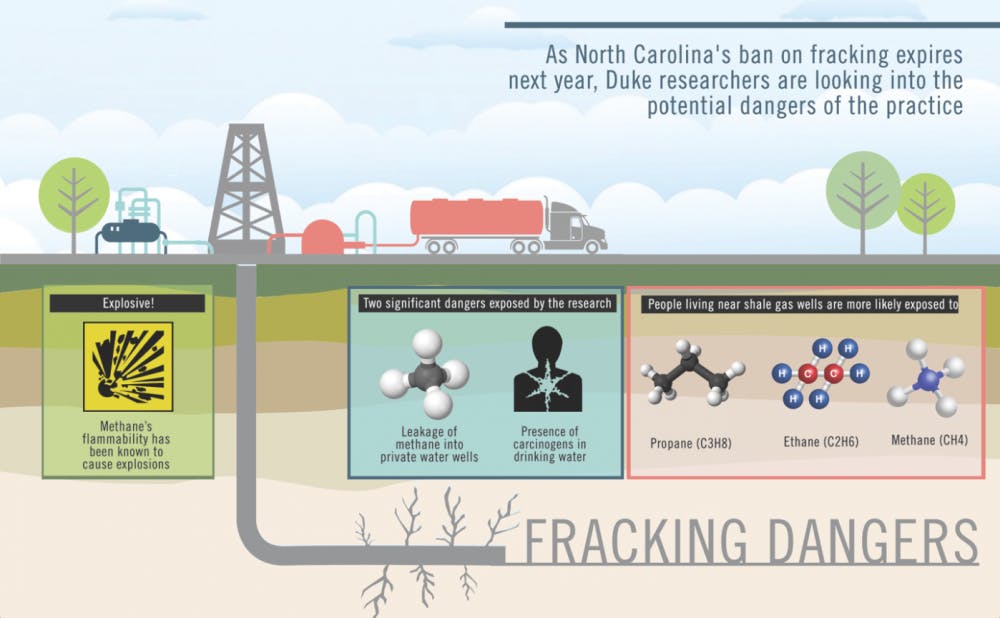

The leakage of methane into private water wells and the presence of carcinogens in drinking water are two of the significant dangers exposed by the research.

“We sampled hundreds of homes with private drinking water wells, and found that people living near shale gas wells are more likely to have methane, ethane, and propane, the components of natural gas, in their water,” said Robert Jackson, formerly of the Nicholas School of the Environment and now a professor of environment and energy at Stanford University.

This becomes a problem in “confined spaces, such as basements, wells, and sheds,” where methane’s flammability has been known to cause explosions, Jackson said. However, the leakage of methane into private water supplies is not necessarily an inevitable consequence of fracking. Research by Jackson and Avner Vengosh, professor of earth and ocean sciences at the Nicholas School of the Environment, has shown that the culprits are faulty pipes, or wells, used while extracting natural gas from below the surface.

“Researchers haven’t found connectivity between the fractures made from fracking and any sort of natural pathway to the surface or aquifers,” said Jennifer Harkness, a graduate student at the Nicholas School currently working with Vengosh. “The gas is not migrating from the fractures made during fracking, but it can be leaked out of poorly formed wells.”

It is against this background of research that the North Carolina legislature is working to institute new regulations when the fracking ban ends next year. The state's Mining and Energy Commission held public hearings throughout August and September to discuss the topic—attracting significant attention from environmental protestors before the Commission drafts its official fracking rules in November.

Jackson said that he believed the legislature was not paying sufficient attention to research from the Nicholas School.

“I think there’s a perception amongst some people in Raleigh that they don’t want to hear about problems that might occur,” Jackson said. “I think the Mining and Energy Commission was designed to establish rules to help drilling come to North Carolina, not to decide whether or not drilling should come to North Carolina. That discussion never really happened.”

The research has also raised concerns about carcinogens being introduced into drinking water supplies. At the end of the drilling, the water originally shot at the underground shale layer to break it apart is brought back up along with the desired natural gas. This wastewater normally goes to a specialized wastewater treatment plant before being discharged into rivers which feed into drinking water plants downstream. However, these drinking water plants often use disinfectants which react with the fracking wastewater to produce potential carcinogens

“Even if the [fracking wastewater] constituted only .01 percent by volume of the river, there would still be a significant shift in the types of byproducts formed, to the more toxic kinds,” said William Mitch, who conducted research with Vengosh as an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford.

There are alternatives available, such as reusing the water for further fracking and deep well injections. However, these options are highly dependent on the geology of the specific area, and are not guaranteed to work. Options at the treatment level, such as reverse osmosis, are extremely cost and energy intensive.

“There really aren’t great treatment alternatives that can remove halides,” Mitch said.

The Mining and Environmental Commission will file its fracking regulations with the state November 20, and drilling companies will likely be able to apply for fracking licenses in the Spring. But Jackson is not convinced that North Carolina will see a big surge in drilling operations even when the ban on fracking ends, citing North Carolina’s small shale reserves in comparison to other states’ as well as a lack of oil and gas infrastructure.

“I’m skeptical that many companies will come to North Carolina any time soon. I think what we will see are wells drilled through subsidies from the state,” Jackson said. “The real question is how much the state is going to spend trying to get companies to come drill here, and I hope the answer is not very much."

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.