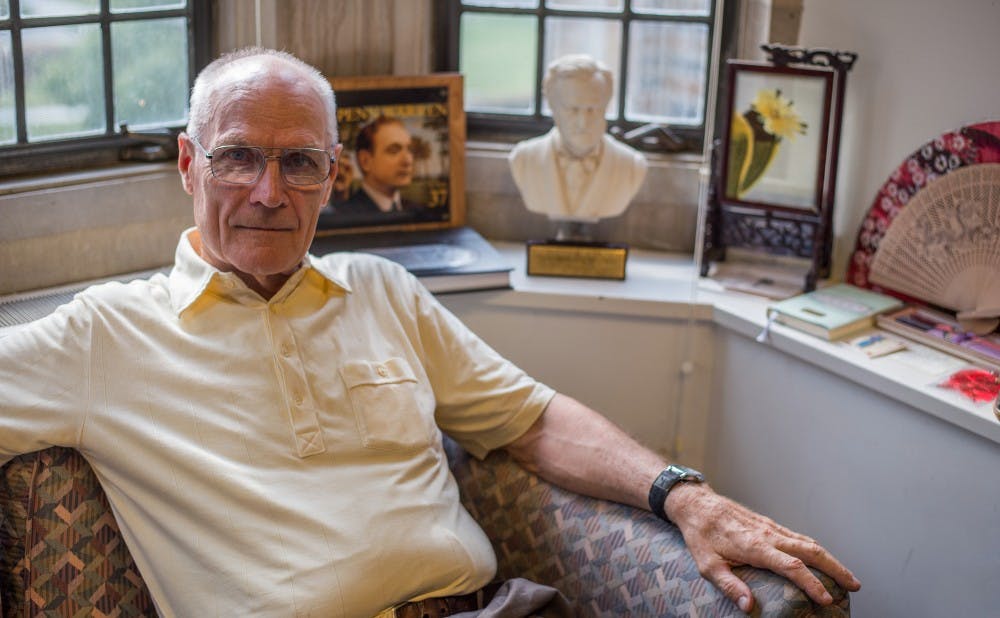

Sitting down with Professor of English Victor Strandberg, the first thing I noticed was the massive bulletin boards behind his desk covered with newspaper clippings and images dating back as far as the 1950s. His office speaks to his love of tradition and history—though Duke has changed immensely in the past 50 years he has taught on campus, Strandberg aims to keep the classics alive.

“The academic disciplines have undergone dramatic change, thanks in part to new technologies in the natural and social sciences and to a new fixation on ideology in the humanities,” Strandberg said. “In my own department and in the humanities at large, I understand that mutability is the iron law of the zeitgeist, but I believe we are also the chief custodians of tradition."

Although there are some aspects of University life Strandberg would prefer to keep the same—like an emphasis on teaching classic literature—his professorship is one that represents transformation. Strandberg has worked under five different Duke presidents, witnessed the expansion of Duke's campus and seen a major curriculum change. His five decades at Duke allows him to talk about the University writ large—the good, the bad and the ugly.

Strandberg the man

A self-proclaimed “full fledged Yankee,” Strandberg was born in New Hampshire in 1935 to a factory-worker father, a mother and two older brothers. Due to his mother’s struggle with mental illness, Strandberg and his brothers were sent to foster homes for the first few years of his life. As a result of this, Strandberg did not meet his parents until he was four and a half.

Although his vocabulary largely consisted of swearing because of his time spent in foster homes, Strandberg was extremely interested in literature as a young child.

“As a boy I read adventure stories,” Strandberg wrote in an email following our interview. “In adolescence I moved on to some classics such as Huckleberry Finn, and in college I reached a mature level of taste with Whitman and Faulkner, whom I still consider our greatest American writers.”

Strandberg became an avid Faulkner reader at Clark University, which was a local college serving the working-class youth of his hometown, Worcester County, Mass. As the first member of his family to attend college, Strandberg did not envision himself going to graduate school, which was also partly due to his difficult financial situation.

Strandberg’s talent and passion in the field of American literature, however, encouraged one of his professors at Clark to not take no for an answer.

“One day he stopped me in the hall with, 'Victor, I wrote a recommendation for you to my friend Hyatt Waggoner at Brown. You did apply, didn’t you?' So I hastily applied to Brown," he said.

Strandberg said he believed he would flunk out of the Ivy League institution. As you could probably guess, he could not have been more wrong. Instead, Strandberg was a standout student and received a fellowship that paid all of his expenses. This allowed him to leave Brown in 1962 with his Ph.D. in hand, free of debts.

Strandberg's own struggle with finances as a student has made him passionate about financial aid at Duke.

“I have had several students in the last few years who have left Duke owing around $100,000, and there must be many more I don’t know about,” Strandberg said. “President Brodhead, to his credit, has focused substantial fundraising efforts on this problem, but there remains too much financial distress out there.”

Strandberg has done what he can to alleviate the financial pressures of students who want a higher education. In 2012, he filmed 25 lectures on the poetry of T.S. Eliot to be published on the internet by Udemy, an online course website. The lectures, free to view, are now available to students worldwide who cannot otherwise afford college.

Before coming to work at Duke, Strandberg spent four years as a professor at the University of Vermont, where he published multiple academic essays and his first book, A Colder Fire: The Poetry of Robert Penn Warren. A unique set of circumstances allowed Duke to bring Strandberg down to North Carolina to work as an English professor: “A senior professor was swamped under a pile of master’s theses, and an eminent colleague in his field committed suicide by jumping out of a downtown hotel window,” Strandberg said.

In the years since he arrived at Duke, Strandberg has created a stable professional and personal life for himself as a distinguished professor. He was married in 1961 to his wife, Penny, and with her has raised two daughters, Anne and Susan, alongside a menagerie of pets—including a duck, a skunk, a rat named Rat, three ferrets and many more. Aside from his variety of household animals, students who inquire about Strandberg’s personal life are often most surprised to learn about his favorite hobby: pouring concrete.

“For 20 years such work during the summer helped support my family; thereafter, I poured concrete for friends or for charities such as Habitat for Humanity,” Strandberg said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Strandberg learned the craft from his father as a child and has continued doing it to this day during summers or stretches of free time. With his many sabbatical leaves to different locations around the globe, however, Strandberg does not spend as much time at home as one would think.

Since beginning his career at Duke, Strandberg has pursued cultural enlightenment by teaching American literature in Sweden (1973), Belgium (1980), Morocco (1987), Japan (1994) and the Czech Republic (2001), to name a few. These sabbaticals allow him to experience new cultures and share his passion for William Faulkner with students across the globe.

Although Strandberg loves his trips working away from Duke, his 50 years spent as a professor show his extreme commitment to the university. Throughout his time here, he has inevitably witnessed many changes within both the campus and academic student experience as a whole.

Strandberg the academic

Strandberg said the most visible change to University life has been the expansion and renovation of the campus, especially the athletic facilities, which can be exemplified through the construction happening on West Campus in the next few years.

As for the students, Strandberg said they have remained generally unchanged. He has observed them year after year in his classroom and believes they have the same academic ability and work ethic, but lately have exhibited an increased commitment to community service. The most common trait the students exude, however, is their love of learning.

“The best part of a teaching career is what happens in the classroom, sharing intellectual enthusiasms with people who have all volunteered to be there,” Strandberg said. “Like, I would guess, most faculty, I consider myself blessed with an ideal job.”

Students in Strandberg’s class thrive on his knowledge and passion of the subjects he teaches, often citing his courses as one of their all time favorites from college.

"Professor Strandberg’s Classics of American Literature class helped me realize how much I love American Lit,” junior Max Stayman said. “He lectures about the books as we read them, including information about the author and historical context. He has an incredible wealth of knowledge… and he presents it in a way that makes sense. And if all that weren’t enough, his teaching style is fantastic; his voice is so unique and fun, and his passion is contagious.”

Lauren Abell Windom, Trinity '05, said taking Strandberg's course as a student inspired her to become an English teacher, and that she has incorporated many of his lessons in her classes as a high school teacher today.

"His passion for the works we studied was so contagious that I found myself taping each lecture he gave so that I would not miss one word. He is not only brilliant, but also witty, charming, and kind," she said. "Even though he often taught larger lecture classes, he took the time to meet with every student to learn more about him or her, and I was always grateful for his genuine interest in what I was doing and the path I was taking."

Although Strandberg believes students’ such as Max’s academic passion have not changed much throughout the years, the content they learn has altered significantly.

Strandberg is a champion of traditional education, and dislikes how it is often undermined in research universities such as Duke. He blames the attitudes of research universities as a collective for this bias against tradition, as in recent years they have begun to prefer professors who innovate to gain professional rewards to those who try and preserve customs of the past.

“As a believer in General Education, I would like to see more emphasis on tradition, perhaps (in the Humanities) by requiring a course in classical music or American history, for example,” Strandberg said.

Curriculum 2000, the set of requirements established in the year 2000 that all Trinity students must complete before graduating, has not helped preserve the tradition that Strandberg values.

“In my judgment, the actual contents of these courses have often been too narrow and specialized to compensate for the lack of General Education,” he said. “The reforms currently contemplated by the Arts and Sciences Council may improve the curriculum somewhat, but serious movement toward General Education will come slowly, if at all.”

Strandberg has different views on how each Duke president has handled academic situations such as this one. Although he values each president's additions to the university, he believes that none are in the "superachiever class of Nan Keohane and Richard Brodhead. The billions raised by the... two and their effective use of that money places them on a level with William Preston Few, the founding president of Duke University."

Strandberg even chaired the committee that assessed Brodhead's qualifications to membership into the English department.

After the committee assessed Brodhead’s scholarship and deemed him a leading scholar in American literature, Strandberg took one step further in helping the Duke English department.

“At my request... [Brodhead] has put his scholarship on line, freely available to whoever is interested,” Strandberg said. “Anyone can just type in his name and follow the links for a rewarding reading experience.”

Strandberg views Brodhead as not only an incredible addition to the English Department, but to the leadership of the school as well. Even with a complicated start to his term—the possibility of head men's basketball coach Mike Krzyzweski going to the NBA in 2004, the lacrosse scandal of 2006 and the recession in 2008—Brodhead has proven himself as a worthy president, Strandberg said. He said specifically that he admires his ability to fundraise, and is curious to see how the newly opened Duke Kunshan University will affect Brodhead’s legacy.

“Unlike these crises, which were thrust upon him, the Kunshan project in China could become his greatest crisis because it is one of his own making, but it could also become the greatest achievement of his time in office.” Strandberg said. “Let history, or destiny, be the judge.”

History has been the judge of Strandberg’s tenure at Duke, and it has proven him an irreplaceable member of the faculty.