Durham is confronting its own conflict-ridden history between police and residents in the wake of events in Ferguson, Mo.

The Durham Police Department has faced several accusations of racial discrimination in its actions and policies in recent years. Statistics show a disparity in Durham police's treatment of white, black and Hispanic individuals—leading some to allege an institutionalized culture of discrimination. Incidents in recent months have sparked new tensions between the department and residents of color, which have been highlighted by the shooting of black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson.

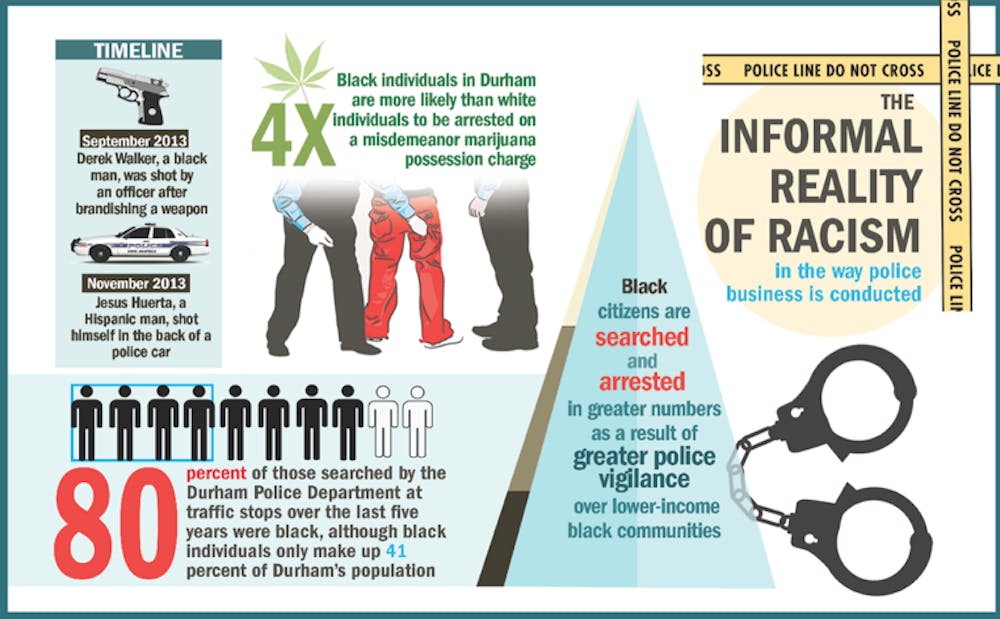

“There’s an informal reality of racism in the way we conduct our police business,” said William Chafe, Alice Mary Baldwin professor of history, who has authored several books examining racial discrimination in post-World War II America.

Although a Southern Coalition for Social Justice report found that more than 80 percent of those searched by the Durham Police Department at traffic stops over the last five years were black, black individuals make up only 41 percent of Durham’s population. Black individuals in Durham are also approximately four times more likely than white individuals to be arrested on a misdemeanor marijuana possession charge, despite strong evidence that white and black people use the drug at roughly the same rate, according to the report. A recent Durham Human Relations Commission report also indicated that racial bias and profiling are present in Durham Police Department practices.

Black citizens are being searched and arrested in greater numbers not because they are committing more crimes but as a result of greater police vigilance over lower-income black communities, said Robert Korstad, professor of public policy studies and history.

“It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy if you just target poor, black neighborhoods,” he said. “The numbers are higher because they’re actually targeting and arresting those people at a higher rate.”

Attorney Scott Holmes, a clinical professor of law at North Carolina Central University, said that police department policies could target black and minority groups without being explicitly race-based.

“When [the police] say that they’re investigating drugs, that’s a euphemism for targeting communities of color,” he said.

Several specific incidents over the past year have fueled tensions between residents and the police department. In September 2013, Derek Walker, a black man, was shot by an officer after brandishing a weapon. Last November, Jesus Huerta, a Hispanic man, shot himself in the back of a police car, igniting protests across the city.

The public perception of police officers has changed, Holmes said—and so has the police’s perception of their own role.

“They don’t look at their role as mentors and mediators in the community,” Holmes said. “They look at their role as people who are going to bust people for drugs.”

But Holmes noted that the problem lies with police culture rather than with individual officers.

“Well-meaning people are actually participating in a racist institution without really understanding the impact that their behavior has on communities,” he said. “You don’t feel like a racist, and it feels unfair when people allege that, because in individuals’ hearts, they aren’t being racists.”

Professor of Public Policy Steve Schewel, a city council member, agreed that although evidence points to a "discriminatory effect" against blacks and minorities, it is unlikely that individual officers were intentionally racist.

Schewel noted that in some instances, officers may simply be responding to calls for assistance from predominantly black or minority communities.

Some Durham residents have called for greater collaboration with the police as opposed to more restrictions on police actions. Citizens marched through the McDougald Terrace public housing community Saturday, demanding more cooperation with the Durham Police Department to end violent crime.

At a city council meeting Aug. 21, City Manager Tom Bonfield addressed concerns about officer-involved shootings and allegations of racial profiling. Bonfield's recommended changes to the police department included requiring written consent for home searches and investigations. He encouraged the use of written consent forms—which document an individual's consent to be searched—for vehicle stops, but left the final decision over whether to use a written consent form to the officer's discretion.

Bonfield’s suggestion that requiring consent forms could jeopardize officers’ “situational control” by making them get the form from their car has been greeted with skepticism.

Officers frequently return to their cars for a variety of reasons, even without having to write consent forms, Chafe noted.

“It’s a fancy word for officers to coerce people,” Holmes added. “If an officer wants your permission to search your body or your car, you are free to leave. In that situation, it’s a consensual encounter. There’s no need to control anything.”

Duke students have responded strongly both to the events in Ferguson, Mo. and to local events in Durham. Last Monday, the Black Student Alliance held a candlelight vigil for Ferguson, drawing attention to incidents of police violence across the country, particularly against black males. Students took a “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!” photo on the Chapel steps last Saturday, challenging biases against black individuals in America.

Racial profiling, whether intentional or not, can be hurtful, said sophomore Henry Washington, Jr., vice president of the Black Student Alliance. He recalled being followed in a Durham clothing store as well as instances where the Duke police response to parties with predominantly black attendance had been disproportionate to the situation.

“I would like to be able to take ownership of my blackness without having it color others' perception of my character,” Washington said.

Despite repeated attempts, the Durham Police Department could not be reached for comment.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.