Public opinion, high costs and geography have contributed to a decline in the use of the death penalty in North Carolina.

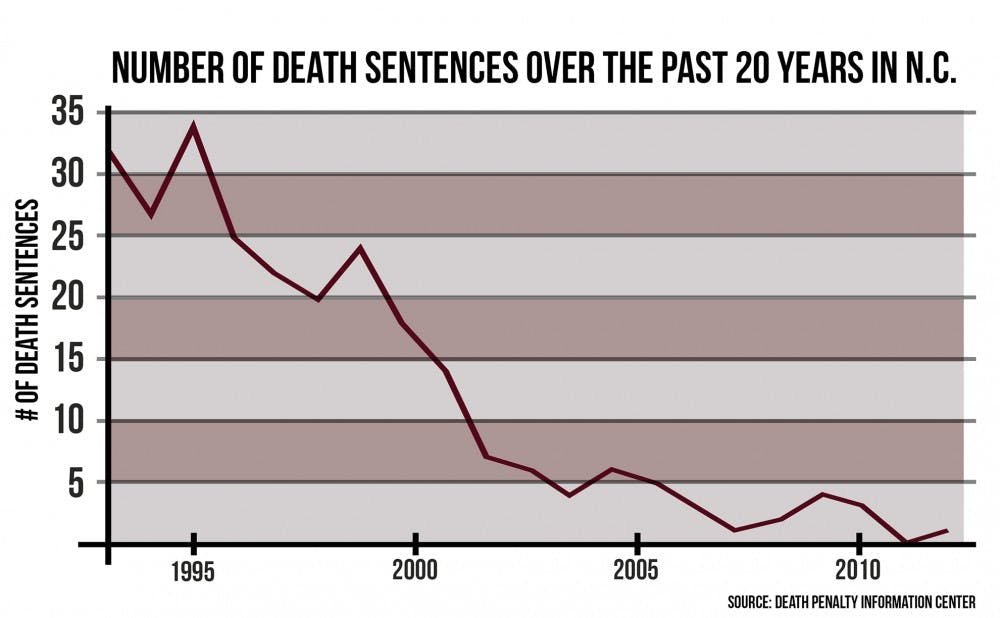

Only one person was sentenced to death in North Carolina out of five people tried for the penalty. The number of people sentenced to death has decreased since the 1990s with 34 sentenced in 1995, 18 in 2000 and six in 2005.

In the past decade, approximately three people have been sentenced annually, said Kenneth Rose, senior staff attorney and former director of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation.

One major reason the death penalty is becoming a less frequent outcome of convictions is because of the large cost associated with it.

“The death penalty is extraordinarily expensive relative to the benefit from it,” said James Coleman, the John S. Bradway Professor of Law and co-director of the Wrongful Convictions Clinic.

If the death penalty is not abolished by law in the future, it will likely die out on its own because of the costs, Coleman said. As defense lawyers gain more experience and skill in death penalty trials, they create more complex trials that are more expensive. Additionally, when people are sentenced to death they will often seek another trial in an attempt to remove the sentence.

“[In] a lot of these cases, if the state didn’t seek the death penalty the defendant would likely plead guilty,” Coleman said. “In many cases, the evidence of the person’s guilt is not really disputed—the only question is whether the person should be sentenced to death.”

The expenses associated with a death penalty trial include lawyers for the defendant, an investigation, reviews by the state supreme court and post-conviction procedures if the person is actually sentenced.

Most of the time, everything is funded by the state because many defendants are poor and have a constitutional right to be represented in court, Coleman said.

“As taxpayers, we’re spending an enormous amount of money for an extremely small amount of return,” said Jay Ferguson, an attorney from The Law Office of Thomas, Ferguson, and Mullins, LLP. “No executions since 2006, yet we still spend millions and millions of dollars for [the trials] per year.”

A discriminatory process

The majority of defendants’ lack of money represents another reason why the death penalty may not be a fair result—the policy has a discriminatory nature, Coleman said.

“The quality of a defendant’s legal counsel is a factor in whether a person is sentenced to death or not,” Coleman said. “There are no rich people on death row. They have good lawyers.”

In addition, race plays a factor. The most likely demographic to face the death penalty is a black person who kills a white person.

“Race permeates death penalty prosecutions, and I think people are tired of that,” Ferguson said.

Coleman also mentioned the mentally ill as another population that has often been treated unfairly by the death penalty. Ferguson recalled one such defendant he worked with.

“He represented himself wearing a Superman t-shirt,” Ferguson said. “He went through the entire legal system until three days prior to his execution, before the court finally stopped him and said he was too insane to be executed. It’s cases like that that make me very wary of the death penalty.”

The number of death sentences is also affected by where the trial occurs. Jurors living in rural areas in eastern North Carolina are more likely to convict defendants than jurors from urban cities such as Durham or Chapel Hill, Coleman said.

He added that rural jurors are more likely to assume police are telling the truth, while urban residents are more likely to be skeptical of the police and sensitive to the possibility of wrongful convictions.

A public wary of a broken system

Increasingly cynical jurors are another reason for the death sentence decrease. More publicity concerning wrongful convictions has resulted in a public skeptical of imposing a death sentence because of the possibility the defendant is not guilty, Coleman said.

“A jury in that situation is likely to convict because they don’t want to let somebody who might be guilty go free, but they’re not going to sentence a person to death because they know that they had some lingering doubts about whether the person was in fact guilty of murder,” Coleman said.

Rose illustrated this issue by pointing to a case in which he represented an innocent defendant who was on death row for more than 10 years, going through multiple levels of appeals before a federal judge finally granted him a hearing. There was “readily available” evidence of the client’s innocence that the trial attorneys did not sufficiently examine during the process.

“Once someone is put on death row, there is a tendency for courts not to second guess the decision to put a person on death row,” Rose said. “I’ve had other clients who were executed without ever having a hearing after their initial trial, and it has showed me, and I think other people as well, that the system is broken.”

A number of public interest groups and defense lawyers have made it their goal to abolish the death penalty, and they have been effective, Coleman said. Reforms include increased leniency for prosecutors who avoid seeking the death penalty, the provision of better lawyers for defendants and a ban on imposing the death penalty for the mentally disabled.

“A lot of individuals believe in the death penalty in theory,” Ferguson said. “But when they’re actually given the choice of life without parole, a majority of North Carolinians believe life without parole is a better option than having the death penalty.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.