On Nov. 21, Persian musician Kayhan Kalhor will perform with Ali Bahrami Fard at the Nasher Museum of Art. This performance will expose audiences to Kalhor's improvisational traditional Persian music.

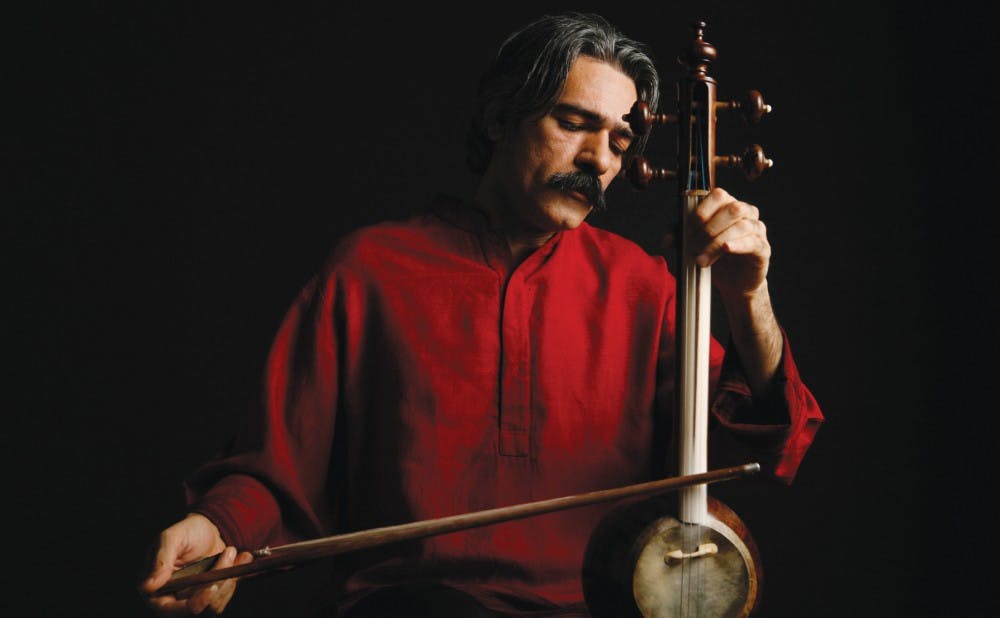

Kalhor plays the spike fiddle, which is often described as the great-great-grandfather of the violin and is played as an “upright fiddle." With a round, hollow soundbox and skin soundboard, the spike fiddle looks and sounds unlike anything in Western music. Kalhor attributed the distinct reedy sound quality of the instrument to its unique design.

“[Kalhor] is one of the real instrumental masters of the world who is able to speak forcefully out of his own tradition but also collaborate with musicians out of other traditions,” Aaron Greenwald said, director of Duke Performances.

This performance was arranged as a direct collaboration with the Nasher's exhibition, Doris Duke's Shangri La: Architecture, Landscape, and Islamic Art, which displays the Islamic artwork of Doris Duke’s home in Hawaii.

“We are trying to collaborate more actively [with the Nasher], and this seemed like a natural one," Greenwald said. "This was the kind of presentation that we could make effectively and somewhat efficiently in the Nasher’s auditorium.”

Kalhor was brought in as the perfect musical complement to this exhibit.

“Kayhan had been an artist in residence at Shangri-La. He had spent time there making work and giving concerts, so there is a direct connection there,” Greenwald explained.

This direct connection allows for Kalhor to give audience members a unique, first-person perspective on the Shangri-La exhibit. Greenwald sees this as particularly important because of the numerous misconceptions about Iranian culture.

“I think we have sometimes not such a nuanced view of the world. We think, ‘Iran—that must be an incredibly culturally repressive place,’ but Tehran in particular has been a place where there has been a lot of cultural richness and vibrancy,” he said.

While he is now thought to be one of the masters of his instrument, Kalhor had rather modest beginnings.

“I lived in a family who loved music, but we didn’t have any professional musicians in the family,” Kalhor said. “Periodically, I saw [the spike fiddle] on TV and in little shows, and I just fell in love with the sound of it.”

This love drove him to pursue a career in music. At the time, this was an impressive feat because there were only a few old masters available to teach the instrument. But this changed after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, as many Iranians sought out their cultural roots again.

“I think music benefitted from [the revolution], and there was a revitalization of music, art and culture. At the same time, a lot of different kinds of music—western classical music and western pop music—were banned. A lot of Iranian classical artists had to feed all of the TV stations, all of the radio stations,” Kalhor said, explaining the effect of the 1979 Revolution on Iranian and traditional Persian culture. “Nowadays, thousands and thousands of young players pursue these instruments.”

“Persian traditional or classical music is very, very old,” Amir Rezvani, Duke psychiatry professor and President of the Persian Art Center in North Carolina, said. “It is rooted in a history of five thousand years. All of these instruments, when played together, give you a feeling of history and culture. It is music different than whatever you hear from pop music.”

And, unlike modern Western pop music, no two Persian traditional music concerts will be the same.

“Persian classical music is based on improvisation and composition,” Rezvani explained. “Based on what you’re getting form the audience in the moment and the feeling, you improvise. One concert is different from another concert.”

Kahlor doesn’t seek to emphasize these divisions between genres of music or regions of the world. Instead, he tries to show the similarities and the ways in which these groups can work together.

“I really don’t think this is very important to talk about because music is a kind of social knowledge to the world because all of the nations have it and love it,” he began dismissively. “They all reflect an expression and a way of people expressing themselves in different cultures through instruments and through playing different instruments.”

This view may be informed by his deep understanding of both Persian and Western culture. As someone who has studied in and lived in Iran and Canada, he is able to work these two seemingly competing musical styles into his work.

“By combining these two—Persian culture and Persian music and Western culture and Western music—Kalhor has been able to cross cultural borders with his work. If you ask me, that is probably one of his missions,” said Rezvani.

While this may be the case, Kalhor sees his mission at Duke and at other performances as much more personal. If others find that his music unites people across cultural borders, then it was because of the interpretation of the music by the listeners.

“The objective is to reach somewhere, to experience something you haven’t experienced before, and then let other people know about it and try to share it with them,” he said.

Ultimately, though, Kalhor wants to be able to deeply connect with his audience.

“I’m sure there is something in the music that reaches somebody’s soul or some part of somebody’s soul. This makes music meaningful. I’m sure whoever comes to this show is open enough to want to experience that.”

Kayhan Kalhor will perform a sold-out show at the Nasher Auditorium on Nov. 21. From 3 to 4:30 p.m. that afternoon, he will give a guided tour of the Shangri-La exhibit. For more information, visit http:/dukeperformances.duke.edu.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.