A black barrier encloses you in a small space. You run around frantically, confronted on all sides by this ominous obstruction. Every time you approach the barrier you immediately run away, unable to cross it. Eventually, you steel yourself and miraculously cross it. It wasn’t a physical obstacle after all.

This is the action of Surekha’s three-minute video “Lines of Control,” but here, the protagonist is an ant and the barrier is a thick black line drawn at the beginning of the video. The piece poignantly examines one of the main themes of the Nasher Museum of Art’s newest exhibition, "Lines of Control: Partition as a Productive Space"—that the difference between physical boundaries and mental boundaries is not well-defined.

Each of the pieces in the exhibition stands alone as an exploration of a single aspect of the tensions between physical borders and social reality. Therefore, it seems fitting that each piece has its own distinct space on the gallery’s walls or floor. A range of mediums is represented in the exhibition—woodblock prints, photography, video, textile crafts, installation—allowing a broad experience in content as well as technique. Viewed together, the pieces offer a critical examination of the relationship between national identity, culture and borders.

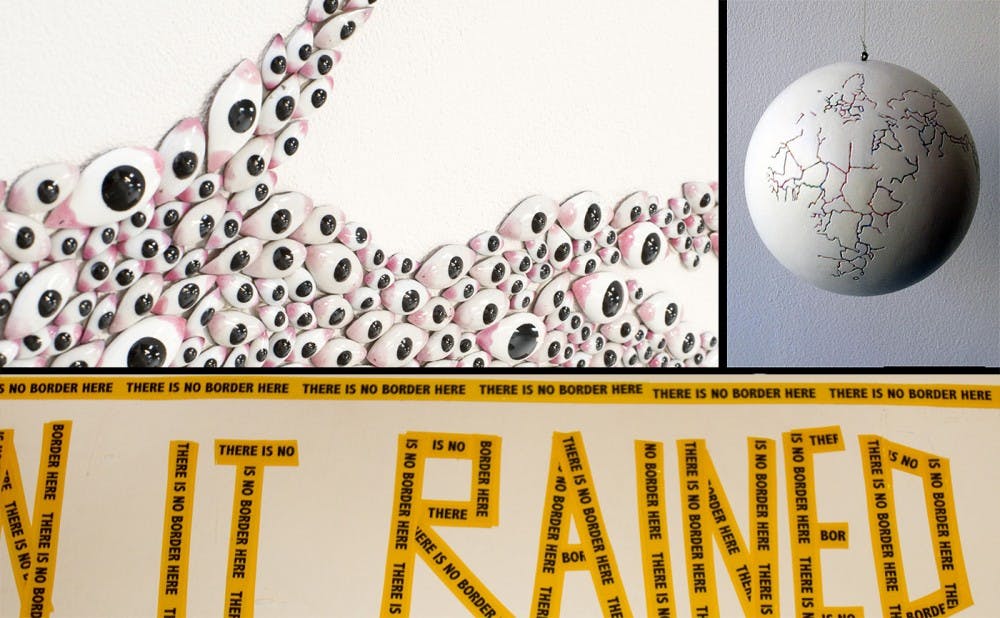

A curving vein winds its way up the wall and branches into thinner rivulets, each made of stylized enamel eyes, that are pointed and oval in shape with dark round pupils. “River/Disease” by Anita Dube takes the form of an aerial view of the rivers of the Punjab region,while also bringing to mind the veins of an eyeball. The piece reminds the viewer that not everything was ruptured and divided by the 1947 Partition of India; the five rivers that give Punjab its name cross the country border, just as the cultural region does. The enamel eyes are manufactured for deity statues in Hindu worship; their use in the piece connects the importance of the rivers to spirituality and to the eye-infecting disease the rivers often carry.

Several pieces feature traditional artisan crafts, making the link between identity and material culture even more evident. Nalini Malani and Iftihkar Dadi’s “Bloodlines” is made of square panels of overlapping gold sequins, severed by red lines marking the border created by Partition. The piece, recently refabricated, was created in collaboration with embroidery artisans that specialize in the traditional metal-wrapped embellishment of India and Pakistan. Another piece, “Afghan (black and red)” by Mona Hatoum, is a rug, in the style that gave the afghan blankets their name, with threads strategically picked out to create a distorted projection of the continents. In both pieces, it would be nearly impossible for someone unfamiliar with the cultural significance of the crafts to appreciate the nuances. Luckily, the descriptions accompanying each work are exceptionally informative.

While the majority of the pieces in the exhibition focus on the India-Pakistan border, several other border conflicts are examined. This not only highlights commonality in the experience of borders, but also reasserts that there are parallels in the origins of these, mostly arbitrary, borders. Namely, the legacy of European empires and colonies, paired with today's intense regulation over human movement, has caused, and continues to aggravate, many modern border conflicts.

For stateless nations or nations that have been disrupted, yearning for ancestral lands is common. Many are now barred from returning and able only to remember. “HOME” by Sophie Ernst combines memory, geography, visualization and language in an effort to immortalize homes of the past. Two installations are on display from the ongoing project that is based on interviews with displaced Palestinians, Iraqi Jews and Indians. White architectural models are overlaid with video projections of sketches made during the interviews, while headphones relay memories of lost homes. The conversation and drawings center on the physical layout of the homes—the discussion of the toilet’s location versus the alley is particularly amusing. At times the sketches seem to match perfectly with the models, while at others they are completely disparate geographies, connected only by the memory that is replayed in the viewer’s ear. Then, the sketch shifts and a new piece of paper is laid out, the discussion still trying to pin down the landscape of the past.

The reality of the Indigenous, or Native, peoples of North America exemplifies the challenges created by boundaries and the limits of language. Jolene Rickard’s “Fight for the Line” overlays images of the Onkwehonwe people's different definitions and dimensions of nationhood—geographical, cultural, linguistic. The Onkwehonwe lay claim to ancestral lands divided by the U.S.-Canada border; they position themselves as a stateless nation who still has rights to its land. Rickard’s piece pushes on the notion of what defines boundaries by combining imagery of maps, signage, protest and photographs.

"Lines of Control: Partition as a Productive Space" critically examines the experience of human-made boundaries, both physical and social. It may be easy in Durham to feel distant from the stresses of border conflict, but the reality is that there are boundaries everywhere. The Nasher invites Duke and UNC-CH students to break down boundaries at a Beyond Blue Borders student mixer on November 7. Perhaps we can reconcile our differences even though we are strangers, just as the final piece in the exhibition invites us to do: “The Translator’s Silence,” by The Raqs Media Collective, can be taken away. Each piece of art is a translucent, tri-folded paper that features three poetry fragments, written in their original languages of English, Urdu/Hindustani and Bengali. The English section reads, “Will you, Beloved Stranger, ever witness Shahid—two destinies at last reconciled by exiles?”

Lines of Control: Partition as a Productive Space is on view until February 2, 2014 at the Nasher Museum of Art. For more information, visit http://nasher.duke.edu/exhibitions/lines-of-control/.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.