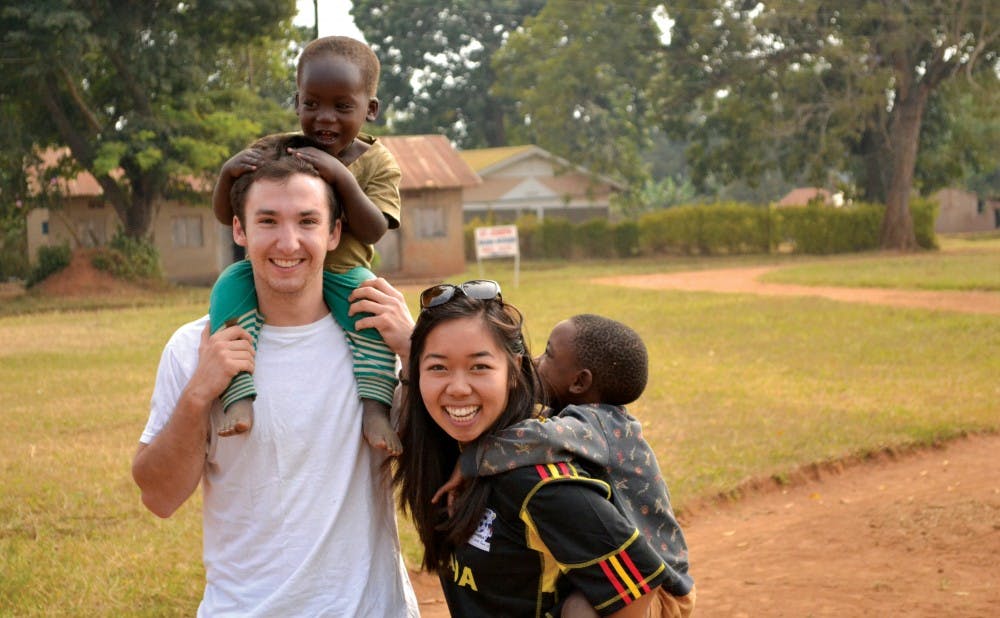

All she could make out were small, outstretched arms, open hands and a chorus of impatient giggles. After ripping paper after paper from her spiral notebook in order to meet all of the eager children’s demands, junior Sammie Truong folded the edges of paper in and out as quickly as her fingers permitted.

It was her fifth day in the parish of Naama, Uganda. She had been waiting outside a primary school, where local health workers were meeting with parents to receive informed consent to run anemia tests on their children. A few students, also waiting, had approached her with eyes full of cautious curiosity. Truong, however, could not speak the language and didn’t know how to respond.

So she turned to an old babysitting gimmick she knew—origami cranes.

As soon as she fumbled together two or three cranes, students flooded the bench she was sitting on. Even though she was making them as quickly as she could, she knew that for every one student that received the origami bird, there would be five or six other students who would go home disappointed.

Although she had barely completed her first week on a Duke Global Health Institute program in Naama, Truong couldn’t help but relate the crane-making frenzy to the various global health issues she had been working on that week and would continue to work on for that entire summer.

“The hardest thing for me was to see the great needs in the community in Naama and accept the fact that we couldn’t help everybody,” Truong said. “Every person that we offered HIV testing meant that there was another person out there who couldn’t have it.”

Duke students are no exception. More and more service-oriented students have turned to programs and curricula that give them an opportunity to translate their academic experiences into tangible assistance.

Since the institute first opened, more than 150 students have earned certificates in global health, and 37 new members have been added to the faculty and staff. In a little more than five years, about 300 students have participated in DGHI-sponsored field research projects in 24 different countries.

Yet since 2006, the only structured academic pathway available for these students passionate about global health has been a certificate.

In response to this rising interest in global health, DGHI will offer a major and minor through the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences beginning this Fall, allowing students to delve more deeply into the issues of global health while still pursuing a more traditional discipline. Although the institute will no longer offer the certificate, students who already began the process will have the option of keeping their certificate, changing to a minor, or adding classes to pursue a major.

“Faculty groups have discussed the creation of a major from the very beginning,” said Gary Bennett, director of undergraduate studies for global health. “The view then was that we needed more resources, faculty and student interest in place and right now the institute has progressed to that point.”

Students who desired a more fully fleshed academic curriculum in global health often had to look for other options not available through DGHI because there was not yet a major.

“Many people focus their Program II in global health because they want a more robust curriculum about the topic, but there wasn’t anything to give them other than the certificate,” said Program II senior Emily Jorgens, who worked with HIV and addiction patients in Durham two summers ago.

In a similar vein, Truong constructed a Program II titled “Global Health: Determinants, Behaviors and Interventions.”

Now students can attain a co-major in global health, which would require students to pair global health with another major. The global health curriculum includes core, foundation, seminar and statistics courses, in addition to an experiential learning activity. A range of experiences, like research, DukeEngage and fieldwork qualify as experiential learning.

While the requirement of complementing global health studies to a major of another discipline may seem arduous and unnecessary, both faculty and students have asserted the significance of an interdisciplinary approach.

“Global health is inherently an interdisciplinary field,” Bennett said. “These problems are complex by definition, which requires multiple disciplines to be brought to face these challenges.”

The interdisciplinary goals of the new major also mesh well with the Trinity College curriculum of liberal arts, which calls for students to “make meaning of complex information,” “apply knowledge in the service of society” and “engage a wide variety of subjects,” according to the website.

Some faculty members, like Assistant Professor of the Practice Sumi Ariely, argue that by having an additional primary major, students will have substantial knowledge from their other major that shapes their critical and analytical perspective on global health issues.

“A practical reason for the co-major is to make sure our students have core training in a traditional major, one that’s been around for years, tested and true, as well as training in global health,” Ariely said.

***

After senior Joy Liu spent the summer of 2011 researching HIV/AIDS in Muhuru Bay, Kenya in 2011 with DukeEngage WISER, she realized that simple patient-to-patient communication was too limited in scope to make the substantial changes in health disparities that she wanted.

Because of this Liu argued that having training in a specific expertise is essential to being useful and effective in the global health field.

While researching reasons why children were not getting properly vaccinated, Liu realized that embedded in a simple question was a larger systemic problem. One of the key problems she discovered was that while the vaccination was free, clinics often charged a service fee that many families could not afford.

“It was more a policy issue and a socioeconomic issue,” Liu said. “There was also the issue of women having to get money from their husbands. The problem exists in how the system works, the fact that they are subjected to this fee they shouldn’t be and that men aren’t engaged in their children’s health.”

After realizing the significance of being able to bring systemic change and wanting to learn a top-down policy approach for health situations like in Muhuru Bay, Liu declared public policy as her first major.

“I felt like I didn’t have any expertise in international development or global health to bring to the table,” Liu said. “Global health is not something you can go in without any expertise and do very well.”

After her second global health experience in Jamkhed, India in 2012, Liu struggled with feeling less useful for the community once again. She encountered issues that seemed irresolvable without actual medical aid, influencing her later decision to drop her global health certificate and pursue biology as a double major instead.

“If I do go to medical school, that’s a breadth of knowledge that is very specific and applicable anywhere that no one can take from you,” she said. “All of my choices at Duke have been framed by what I think I can do for global health.”

Junior Ben Ramsey, who also participated in the same Naama, Uganda project with Truong, was initially drawn to global health issues in high school through initiatives like Doctors Without Borders. But at the time, he believed that these issues were strictly medical and in need of only that type of expertise. It was not until he took the Introduction to Global Health course as a sophomore at Duke that he realized it enveloped so many more disciplinary approaches.

“In a team, you’re going to need to have different opinions based on what you’re knowledgeable about,” Ramsey said. “As a public policy major, I would always come in with a policy perspective that these issues need.”

“Some people might argue that a career like investment banking might be the opposite of global health—that it’s hurting the globe, rather,” Ariely said. “But their training in global health enhances their understanding of how to be a global citizen and offers a unique perspective of the world in that industry.”

***

Duke has long prioritized helping students understand their global citizenship and use their privilege and education to bridge the gap in health disparities. Taking on these responsibilities has pushed DGHI to organize and develop adequate preparation and reflection processes for its students.

For example, the Student Research Training Program, a DGHI experiential learning component, dedicates an entire year to preparing participants. Not only do students have to attend bi-weekly meetings with their faculty director, but they also engage in workshops and meetings to familiarize themselves with their on-site community’s culture, as well as communicate with their local partners.

“What I thought was great about the Naama project was that it was a group effort and not just Duke coming in, playing our part, and then leaving,” Ramsey said. “The community definitely had ownership in what we were doing.”

DGHI faculty and staff also stress the importance of preparing students emotionally before the summer. Programs like DukeEngage and DukeImmerse have similarly agreed with these priorities. While the rapidly increasing interest in global issues is both significant and exciting for faculty, this calls for an equally evolving and available infrastructure for reflection.

“Students carry so much of their experience in different ways,” Student Projects Coordinator Lysa MacKeen said. “Re-entry is enormously stressful. Students come back and struggle with understanding why they’re here when they were providing free health screenings in Uganda just a few weeks ago.”

In years prior, DGHI held four mandatory workshops over the course of two months for students who returned from their summer programs. While the workshops were effective to a certain extent, schedule conflicts led DGHI to experiment with a different post-fieldwork processing method.

“We want students to be able to take all they learned into this more practical realm and enrich the education they have here,” MacKeen said.

This type of investment in undergraduate students interested in global health is unique to Duke, say some people involved with DGHI.

“We have put very serious resources in advising, classrooms and experiential learning,” Bennett said. “We have chosen to make the investment in the undergraduate side, and now we have this type of infrastructure ready for our students.”

Through the emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration with diverse faculty members, DGHI has been able to venture to what some would call a new frontier of academia. Moreover, DGHI also remains unique in that it couples students’ academic experiences with intensive and extensive experiential fieldwork programs.

While this experiential learning requirement offers students the opportunity to help communities in need, their contribution is, in reality, limited. Repairing a broken health system or finding the cure to a certain disease is not the heart of the mission for the program itself. At the end of the day, students are not doctors, nor are they legitimate policy makers just yet.

“We want to make sure that participants are learning and serving in a way that helps and enhances them, and provides them with the educational structure they need,” Ariely said. "Our first mission is to educate our students.”