Green lamps dangle from a ceiling framed by ornate carvings. The tirelessly detailed patterns, eclectic and timeless, continue along the walls, arched windows and crevices. The colors, some rustic and some pastel, rise in contrast to the floor with its shiny off-whiteness and large geometric designs. Oil lamps, water pipes and perfume bottles tastefully adorn tables and shelves. Golden Arabic calligraphy panels the walls above, and the photograph is taken in such a way that you feel as if, with a single step, you could enter into the "Syrian Room." Tim Street-Porter’s large and backlit photograph welcomes viewers into the Nasher’s newest exhibition opening Thursday, August 29: Doris Duke's Shangri La: Architecture, Landscape, and Islamic Art.

Doris Duke is somewhat shrouded in mystery. She’s consistently hailed as an American heiress and philanthropist, yet she never kept any journals for modern scholarly reference. She was a private person—private enough that rumor and scandal, even now, manage to work their way into the mainstream's perception of her. In the same way, Islamic art, despite its deep tradition and history, is a sort of vague novelty to Western canon. This will be the first major opportunity for the Nasher to expose its audiences to Islamic art.

Shangri La is Doris Duke’s mansion, commissioned and envisioned entirely by the heiress. The massive property is simple—even austere—on the outside, but the interior flourishes with Islamic art, furniture, jewelry and architectural elements curated by Duke herself.

“It was her living space,” said Mary Samouelian, former Doris Duke collection archivist. “She interacted with the objects and she lived in those spaces. It was probably her favorite home; it was hers, designed and built from the ground up.”

Duke lived in New York City right beside the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it is speculated her love for art originated. For her honeymoon in 1935, Duke traveled across the world and fell in love with the Taj Mahal. Already attracted to art and architecture, she was inspired by what she discovered. Her second trip in 1938 was to the Middle East. Flying over in a propeller plane and shipping over a car, she embarked throughout several countries over the course of six weeks with one goal: to furnish and decorate Shangri La.

“It’s important to think about this as [works of art] that Doris Duke owned and cared for,” said Katie Adkins, coordinating curator for the exhibition. “She embraced Islamic architecture and that went into the whole idea of the house and how she would set the work up. When doing a show about an art collector like Duke, it always gets at the fact that someone lived with, someone loved and someone chose this art.”

What distinguishes this exhibition is that it is inseparable from its context; the house and the art are symbiotic. Groupings and rooms were used to create the essence of a home and also an educational platform for Islamic art. Each space serves a purpose. Documents and works of art, whether from the Rare Manuscript Library or the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, are methodically spaced throughout.

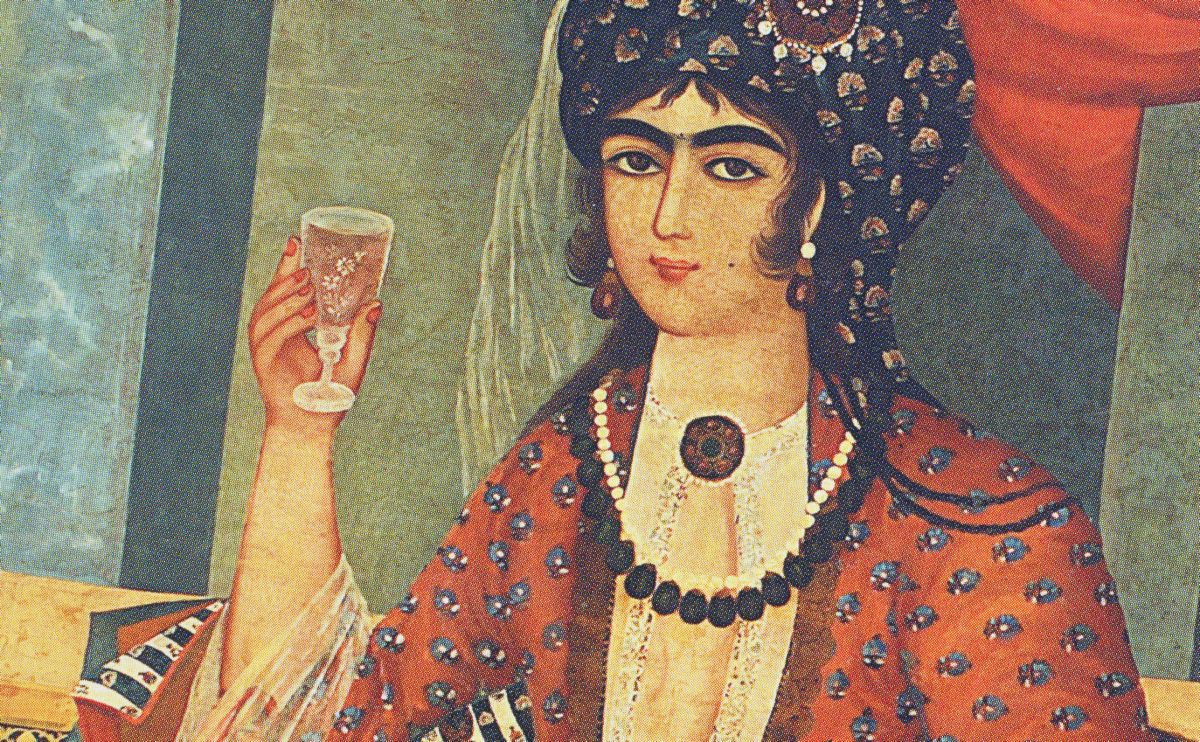

Visitors will see elegant vases and hardy bureaus alongside a small model of the property and old architectural sketches. One particularly iconic portrait is that of Doris Duke in a fashionable, Islamic-style dress (displayed alongside the photograph) as she looks on fiercely.

The final room of the exhibition features a grouping of contemporary artwork. These include "There is Nothing Like Him," ink and gold on Turkish ahar paper in talik script, and the massive "Heart Axe," a sheer sheet of polyethylene with thousands of tiny cutouts to compose a design similar to those on the walls of Shangri La.

It seems obvious that an exhibition with works compiled by the only daughter of James B. Duke would be on display at Duke University. What is less apparent, however, is what this exhibition reveals about Doris Duke—the side that is rarely portrayed by the media or by posthumous biographies, much of which focuses on distorted and often inaccurate accounts of her life and its associated scandals.

“Enough time had passed where people really needed to understand who the real Doris Duke was,” said Samouelian. Duke’s collection and her home, then, are the venues by which viewers can discover what Duke was really like as a person.

“[Duke] spent her time with artists and people from all walks of life,” continued Samouelian. “She was very interested in and accepting of other cultures. In the same way, she was not an elitist about art. There is a huge range of art that might have caught her eye.”

The greatest legacy left behind by Doris Duke and Shangri La extends beyond the collection. In the 1965 version of her will, she stated that she wanted Shangri La to become a place of study for Islamic art and culture. Her vision came true: every year, artists and scholars have the opportunity for residency in Shangri La, and the estate is now open for public visitation. This exhibition furthers what she had envisioned, presenting the chance to discover Islamic art and understand the culture behind it.

“The hope is for others to also develop a love for Islamic art,” said Adkins. “This exhibition gives [viewers] the opportunity to see these works and think about what it’s like to have an art collection, what it’d be like to live with these works in particular and what that means.”

Doris Duke’s Shangri La opens at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University on Aug. 29 and runs until Dec. 29. For more information and associated events, visit http://nasher.duke.edu/shangrila/.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.