It is apparent from the beginning of Baz Luhrmann’s most recent film, The Great Gatsby, that the movie will be a polarizing feature. Taking on the most famous work of author F. Scott Fitzgerald, Luhrmann’s visually magnificent and aurally hip version of the book is avant-garde, to say the least. While there are underlying flaws that come with the territory of translating such a nuanced novel to the big screen, the flashy sounds and visuals allow it to shine as an enjoyable feature.

The Great Gatsby takes on themes of love, greed and corruption of the American Dream in the jazz age of New York City. A young transplant, Nick Carraway, narrates his summer spent befriending his dazzlingly wealthy neighbor, Jay Gatsby, and his subsequent disillusionment with the New York elite. It’s a timeless classic, but this is a Gatsby unlike any other. There have been adaptations before, but none quite as sexy. Flashy cars, a soundtrack that blends twenties swing with modern rap and party scenes that are oddly reminiscent of those on a college campus combine to yield a much younger version of the book read by many in high school literature classes. At the same time, however, Luhrmann stays true to the story; most dialogue is straight from the novel, and plot-wise, he follows the book rather well. Carraway’s romantic life is ignored, but the sad pensiveness of the novel is retained as well as much of the main action.

The visuals in particular cannot be overestimated. There’s an abundance of articulation in the book, but not action, and putting a screenplay together full of dinner dates and tea parties was likely challenging. The camera angles and intense colors Luhrmann uses to keep the interest of the viewer are incredibly effective—one can hardly tear their eyes from the sparkling extravagance characterizing the party scenes. The soundtrack is another plus. Roaring jazz remixed with artists such as Jay-Z and Lana Del Rey makes for some seriously fun listening, and the songs will likely gain their own fame apart from the film. Paired with the visuals, it’s clear that Luhrmann had a clear vision when making the movie, and he executed this vision with great effect.

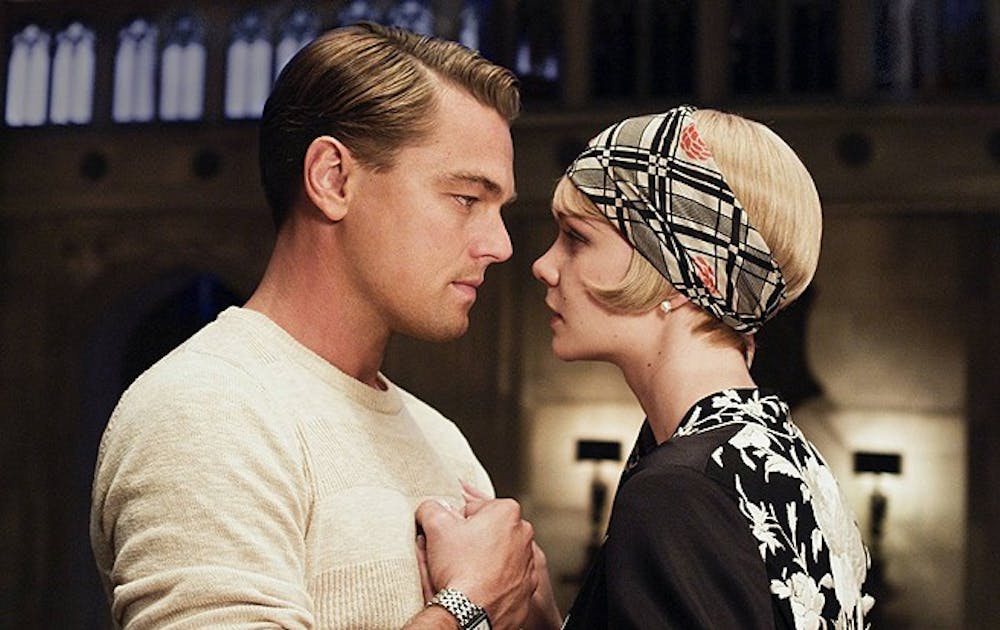

In contrast with the production, the acting is a mixed bag. Leonardo DiCaprio gives the solid performance moviegoers have come to expect, but surprisingly it’s Daisy’s husband, played by Australian Joel Edgerton, who gives the richest performance of the movie. He is the only character who seems fully comfortable in his role—some of the lines, taken straight from the book, seem awkward coming from Tobey Maguire’s narrator and appear forced, as do some of Leonardo DiCaprio’s accented speeches. This is the most superficial appearance of the underlying problem: as a full adaptation of the novel, the movie has its drawbacks.

The fundamental issue with Gatsby is that the nuances the book conveys so well in prose are often difficult to translate on-screen. Much of the significance of certain lines is lost as the movie is forced to move the plot forward: for example, when Daisy says she hopes her daughter is a “beautiful little fool,” it comes off as odd and unsettling, without the profundity felt in the text. The film is also long; at two and a half hours, there are parts that tend to drag and noticeably lengthen the movie. It’s a good version, but maybe not the great one that Luhrmann hoped for. Still, the movie is a testament to the recent trend of heavily computerized visuals and updated soundtracks, as well as the director’s visionary style. This is not the easiest book to adapt, and Luhrmann delivers a fresh new Gatsby that is fun to watch.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.