Before biology, there was botany and zoology.

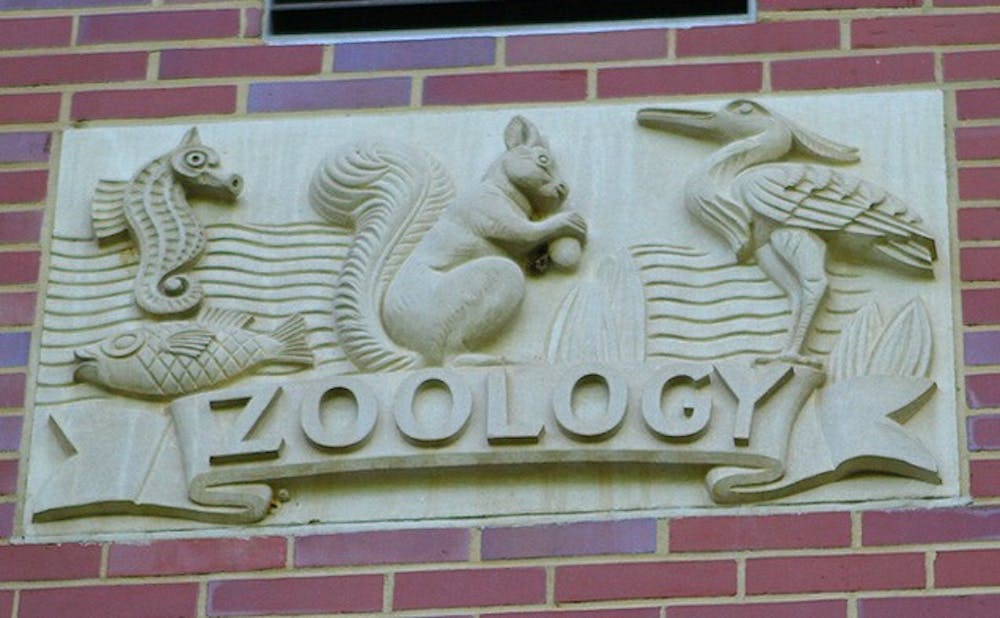

The Duke biology department did not exist before 2000. Botany and zoology were free standing departments that sometimes collaborated, but harbored tension with each other. On July 1, 2000, zoology and botany merged and became biology. The department of forestry had shared the space as well, but became part of the Nicholas School of the Environment in 1991. The last tangible evidence of a divide between the two sits above the Biological Sciences building, where there are three carvings depicting botany, forestry and zoology.

“Biology isn’t divided arbitrarily into plants and animals—plants and animals do a lot of the same things,” said Jim Siedow, vice provost for research and professor of biology. “So if you’re a cell biologist, whether you work on plants or animals, you’re asking the same questions. That didn’t used to be true in the early days.”

Siedow, who was then a professor in the botany department, chaired a 1996 task force that recommended merging. In the early days, he said, there was a greater distinction between plants and animals. As science developed over the years, however, that distinction became blurred and separate departments focusing on plants and animals no longer made sense.

A rivalry tested

Merger was not so easily accepted by all faculty. Although the zoology and botany departments had shared the Biological Sciences building, equipment and sometimes classes, the faculty felt a strong sense of rivalry.

“Botany was on the right hand wing as you’re facing the front of the building. The middle wing was pretty much all zoology and the left wing was the school of forestry,” Siedow said. “It was almost like there was a wall that separated the botany wing from the zoology wing.”

Siedow noted that the rivalry spread beyond work.

“When there were parties at peoples houses, and you went to a botany person’s house, you never saw any zoology faculty there,” he said.

Many of the relationships between faculty members of different departments were individual, and not widespread throughout the departments, he said.

“There were some close relationships between faculty in botany and zoology, but certainly not among the older people where the competition was rather steep,” Siedow added.

Although merger had become a national trend, faculty in both zoology and botany were resistant to the change. Talks of merger also intensified tension between the departments.

“A number of zoologists had said, ‘well a zoology degree is a biology major,’” Siedow said. “And that was not well received because the zoology major didn’t address plant biology at all. That sort of attitude made people not want to merge into the same department.”

Plant biologists were also concerned that the merger would be “the death of botany,” Siedow said.

“The notion that a merger was going to lead to the detriment of plant biology really drove a lot of the more senior plant biologists away,” Siedow said.

Siedow noted that merger was proposed a number of times before discussions as to how to implement could even occur.

“Anytime a big change is proposed for any group there is concern about what could go wrong or what could go badly,” said Professor of Biology David McClay, who was part of the zoology department before the merger. “That sentiment certainly was felt and it created a tension at the time.”

Beyond interdepartmental tensions, biology professor Kathleen Smith, who served as the first chair of the biology department, noted that of the issues during the merger were administrative or related to the increased size of the singular biology department. While botany and zoology had about 20 faculty members each, the combined departments were larger and thus a consensus was harder to come by.

Behind the ball

Across the country, universities had already begun combining their botany and zoology departments. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill had consolidated its departments in 1982, and Siedow said UNC was certainly not the only university leading the trend.

“Duke was late,” Siedow said. “Merging had been going on around the country for quite some time.”

Although late to a full-scale merger, Duke had already taken many steps to integrating the two departments to address the needs of undergraduate students.

More than 10 years before Duke officially combined the departments, zoology and botany had already merged on the undergraduate level, and Duke provided a single biology major to students. The graduate programs, however, had remained separate, and professors still belonged to separate departments.

“Undergraduates were complaining that in competing to get into medical school, botany and zoology weren’t seen as ‘with it’ degrees,” Siedow said. “Even though… nothing really changed in the curriculum other than the name of the degree. There was a concern that our undergraduates were at a disadvantage because they didn’t have biology degrees, so we totally merged everything [on the undergraduate level].”

Beyond both faculties’ collaboration on the undergraduate level, faculty members worked on many joint projects and shared intellectual interests. An early example of collaboration was the Development, Cell and Molecular Biology group, which was composed of botany and zoology faculty who studied cell, molecular and developmental biology.

McClay was a member of DCMB and said half the group used animal model systems while the other half used plant model systems, but faculty from the two departments worked quite well together. The departments’ ability to collaborate helped support the merger.

“When the idea of merger of the departments came up it was easy to support the merger because it would mean we would continue to work with our colleagues who worked with plant model systems, but now it would be easier because we would all be working under the same administrative leadership,” McClay wrote in an email June 18.

Today, the future of the biology department looks bright. Siedow acknowledged that the only way to maintain itself as contemporary department and address contemporary issues was for botany and zoology to merge into biology.

“Biology is one of the strongest departments at Duke and is one of the best biology departments in the country,” Smith said. “The faculty members in the department have tremendous respect for each other, and are very supportive of other faculty members.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.