Local Durham residents and several Duke Divinity School students gathered at the intersection of U.S. Route 15-501 and Mt. Moriah Road Monday to protest a Dec. 17 change to Durham ordinances that outlawed begging on the medians of major roads.

In the past, the city of Durham allowed begging on medians as long as panhandlers wore reflective hazard vests and registered with the city. The new ordinance bans sitting, standing or walking on medians as well as being on an access ramp, requiring instead that panhandlers stand on a sidewalk on a one-way street or the lane closest to the edge of a roadway and at least 100 feet from a bridge. Donations can only be accepted from the passenger side of a vehicle. Many local panhandlers have been ticketed and fined since the ordinance went into effect.

Open Table Ministries and several local pastors organized the recent protest. The protest purposefully took place in an area where protestors are not allowed to even receive a permit for gathering, said fourth-year Divinity School student Emily Knight. “In every possible way we are protesting the ordinance,” Knight said.

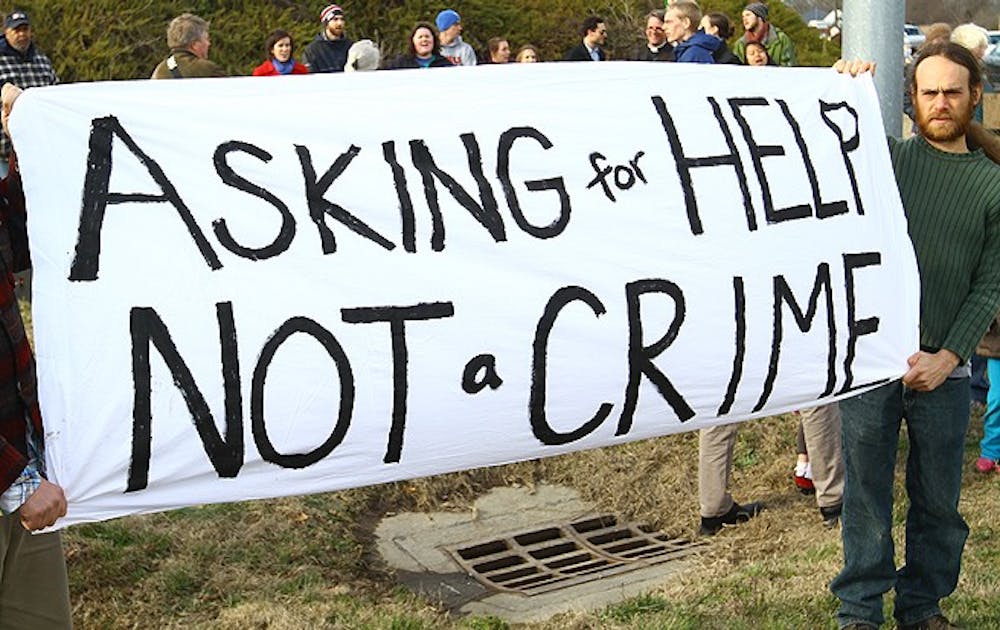

Knight was one of several Duke Divinity students who participated in the protest, while other protestors ranged from local senior citizens to children as young as four years old. Some protestors wore reflective vests and stood on the medians to directly violate the ordinance while others remained on the grassy slope next to the highway. All participants carried signs written on cardboard mimicking the handmade signs typically carried by panhandlers. Some of the signs were shakily drawn by a small six-year-old girl named Sarah, who ran through the grass on the side of the road during the protest.

Local residents Jean and Bob Kruhm heard about the protest during a meeting at the Watts Street Baptist Church and came out to support it. Bob said that neither he nor Jean had realized how the new ordinance made it difficult to for the poor to get by in Durham.

Jean said that she objected to the way the ordinance was passed without any investigation. Knight also felt that the ordinance was passed without considering or creating alternatives for the people who are most affected by the change. “My problem with the ordinance is that it takes a marginalized population and quite literally forces them off the street, making them invisible,” Knight said. “That is wrong.”

Within thirty minutes of the protest, the police arrived. Instead of ticketing the protestors, they handed out white fliers detailing the stipulations of the new ordinance.

One of the officers, who declined to give his name, explained that they had been called in because a person in the area had called the police reporting the protest. The other officers refused to comment.

Second-year Divinity School student Adam Baker heard about the protest through friends, and he estimated that there were 10 to 15 other Divinity students at the protest.

“A number of [Divinity School students] have actually driven by and honked and waved, and some of us are out on the medians as well,” he said.

He noted that as a Divinity school student, he felt that he is trained to be aware of the reality of need in his community.

“[We are trained] to not just speak about ministry as an idea or a theory but to see it as something that people live out on a daily basis,” he said. “[Standing here for the protest] is a minor deal compared to what people stand out and do on a regular basis as part of their regular lives.”

He said the protest has changed how he views the homeless.

“I’m definitely the sort of person who would have just driven by people standing on medians before and not made eye contact—more out of a sense of guilt or not knowing what I can do that’s effective in some way,” he said.

In the future, though, Baker said that he would approach panhandlers with a new perspective.

“If I don’t have anything to give them, I will at the very least make eye contact with them and smile and acknowledge them as a person—because that’s what they are—rather than consider them to be an annoyance or somebody to be ignored because they make me feel uncomfortable,” he said.

Bob Kruhm had also never contributed before, but he said that he does now because he felt that people should treat panhandlers with dignity in tough times. Robert Simpson, a pastor at Resurrection Methodist church, became involved with the protest through his work with Open Table ministries providing meals for the homeless weekly.

“I just hope that people of Durham can be aware of [the ordinance] and that it is our responsibility as people of God to help out everybody,” he said. He attributed his new perceptions of the homeless to his involvement with Open Table.

“Before, I would give help at a distance, but now I’m meeting them and actually seeing them face-to-face—you can’t be the same when you see them face-to-face,” he said. “It’s really life changing.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.