Students have taken issue with apparent unfairness in course credit assignment for time-intensive lab classes, and now faculty are looking at ways to change it.

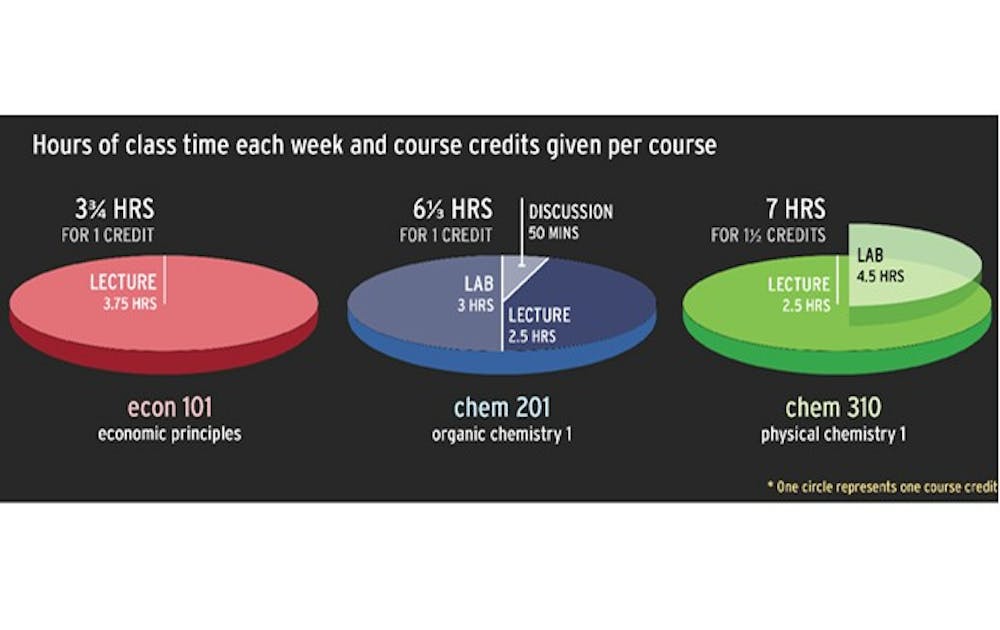

Under the current course credit system, the hours spent in class do not factor into the credit value assigned to a course. This means students can receive the same amount of credit for a class that meets a few hours a week as for a lab class that meets several hours more. Students have identified this disparity particularly in physics, chemistry and biology courses, where lengthy labs are necessary components of that area of study.

Faculty from the chemistry and physics departments are addressing the disconnect between time spent in a class and the credit awarded by proposing the addition of course credit to lab classes.

“We want to restructure undergraduate courses so that we can keep the quality high and make it more equitable,” said Ashutosh Kotwal, physics professor and associate chair for teaching.

Kotwol is an ex-officio member of the Undergraduate Experimental Physics Committee, a faculty committee in the physics department that is considering separating the laboratory component of certain physics classes to be a stand-alone course carrying course credit. The committee will be convening at a faculty retreat in April to discuss the proposals.

The chemistry department has had similar discussions for course credit re-evaluations, including assigning the lab portions of Chemistry 101DL: “Core Concepts in Chemistry” and Chemistry 201DL: “Organic Chemistry” as separate 0.25 credit courses. Advanced physical chemistry courses such as Chemistry 301, 310 and 311 already have standalone laboratory courses Chemistry 301L, 310L and 311L that each carry 0.5 course credits.

Credits where credit is due

This increase in credit for labs would be a step in the right direction in the eyes of chemistry major Victoria Reynolds, a senior. She said the higher-level chemistry classes such as physical chemistry deserve a stand-alone 0.5 credit, if not more.

“I feel like I put more work into the lab portion than the actual class,” Reynolds said. “Even though lab was every other week, given the amount of preparatory work and the time spent on the write-up afterwards, you would usually spend 20 hours every two weeks on the lab report.”

The discussed reassignment of course credit would only apply to the courses of the physics major in which class time reviews physical principles while labs teach students how to use instruments and design an experiment, said Daniel Gauthier, Robert Richardson professor of physics and chair of the committee. The concepts in lab are not directly in support of the concepts from the lecture portion of the course, so the lab component can be a class of its own.

Chemistry labs, too, include material that is not directly credited, said sophomore Krishan Sivaraj, a biology major.

“Most of the material that was covered in chemistry lab was never covered on a test, so it would have been much more beneficial if I had received some course credit for my work,” Sivaraj said.

The physics committee, however, will not consider adding credit to lab sections for life science and engineering-based physics classes. The lab portions in the introductory engineering and life science-based physics classes are closely connected to lecture material and are an integral part of learning the in-class material, Gauthier said.

Additionally, because tuition for summer courses is paid for per course credit, adding an additional credit for lab would create an increased financial burden for students taking classes over the summer, Gauthier said.

For the chemistry department, adding a separate 0.25 credit to general and organic chemistry courses would be consistent with what is done at many other institutions that operate on a course hour system, where courses with both lectures and labs are often offered as four or five hour courses, Richard MacPhail, co-director of undergraduate studies of chemistry, wrote in an email Sunday.

This addition would alleviate student concern over the credit they are receiving for the time involved in labs.

Certain courses are “infamous” among students for their time-consuming labs, such as Physics 264L: “Optics and Modern Physics,” said physics major Alex Wertheim, a junior. Many of the labs involve taking a lot of time and working with sensitive equipment. It would be encouraging for students to see the amount of time they put into lab translate into actual course credits, he added.

Offering an additional 0.25 credits for the lab portions of general and organic chemistry would recognize the time students put into lab, Reynolds said.

“The lab portion does not usually have a big impact on your grade, unless you stop doing the labs,” Reynolds said. “The issue is that students are not rewarded very much for putting time into the lab portion of the class.”

There is no specific timeline in place to officially add 0.25 credits to lab courses, MacPhail said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

‘Contact hours’ in lab courses

One recurring topic of debate on course credit re-evaluation is a course’s contact hours, the time that students spend in the classroom, said Steve Nowicki, dean and vice provost for undergraduate education.

The University currently operates under a course credit system, in which students are given 1.0 course credit per course. Under this system, courses such as Chemistry 201DL that have a discussion, lab, and lecture component have the same credit value as a class with fewer contact hours such as Writing 101: “Academic Writing,” which only meets two hours and 30 minutes a week.

Lee Baker, dean of academic affairs of Trinity College of Arts and Sciences and associate vice provost for undergraduate education, noted that Duke uses the course credit system because the “scope, scale, and intensity of learning” should be measured both in and out of the classroom.

The course credit system also eliminates “unproductive” discussion about whether a course should be worth three or four credit hours, Nowicki noted. In the modern-day classroom, where there are online materials and work done out of class, in-class contact is a poor measure of the effort students put into a class.

“It’s invidious to use class time as a measure of effort,” Nowicki said. “It’s true that engineering courses require you to be in the laboratory, but that is only because the work you are expected to do can only be done in a lab. However, if you’re a literature class, you are spending hours in the library on research. It is hard to say which class requires more work.”

Offering a diverse range of courses is more important than counting the time spent in a class, said Paul Manos, director of undergraduate studies in the biology department. Lab and lecture should help students form a “cohesive body of knowledge.”

Manos cited the current model of Biology 202L: “Genetics and Evolution” as an example of cohesive learning. The course, which uses the “flipped classroom” model this semester, prompts students to take their own initiative in learning class material, and the success of the course so far shows that it is paying greater dividends.

Biology 202L, which is currently taught by Mohamed Noor, Earl McLean professor and associate chair of biology, requires students to watch pre-recorded lectures on Coursera, complete an online quiz and make notes of concepts before attending class. By doing so, class time becomes tailored to student discussion.

“It’s the experiential learning that creates a solid curriculum for students,” Manos said. “For many science classes, you can’t just get the course from the lecture—you need the lab aspect. The investment of time is part of the agreement for students that are taking courses rooted in the natural sciences.”